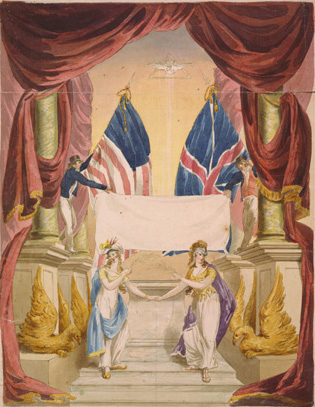

The conclusion of the War of 1812 was eagerly anticipated. Expensive and unpopular among both British and American citizens, the news of peace was greeted enthusiastically by everyone affected by the war.

Americans boasted of how they had “unqueened the self-stiled Queen of the Ocean,” defeated “Wellington’s invincibles” and become “the conquerors of the conquerors of Europe.” They forgot the war's causes and ignored how close they had come to defeat.

Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

Lord Castlereagh, Britain’s foreign secretary, congratulated Prime Minister Lord Liverpool on “being released from the millstone of an American war,” and a British official at Vienna reported that the news of peace had “produced an astonishing effect,” helping to foil a Russian bid for aggrandizement. All agreed that without the distraction of a war in North America, Britain’s hand in Europe was strengthened. Events in Europe that had caused the War of 1812 and then shaped its course now helped bring it to an end.

The news of peace was greeted in America with relief, and there were celebrations and parades across the republic. Even the most ardent war hawk showed no interest in continuing a war that had turned decidedly sour and now offered little prospect of any concrete gains. Under these circumstances everyone realized that a return to the status quo ante bellum was the best that the United States could hope for.

Most Americans do not remember that the war had ended in a draw on the battlefield or that the maritime issues that had caused it were not even mentioned in the peace treaty. Andrew Jackson’s spectacular success at New Orleans, coupled with the naval victories on the high seas and the northern lakes, shaped the postwar memory of the conflict. Americans boasted of how they had “unqueened the self-stiled Queen of the Ocean,” and defeated “Wellington’s invincibles” and “the conquerors of the conquerors of Europe.” They forgot the causes of the war and ignored how close they had come to defeat.

Americans also lost sight of how closely this war was tied to a much larger conflict in Europe. To the British, the contest was but one theater, and a decidedly minor one at that, in a multifaceted war that they were waging against the Crown’s enemies on both sides of the Atlantic. Throughout this period, Britain’s perspective was preeminently European. Her focus remained firmly riveted on the Continent, her top priority always being to prevent France or any nation from dominating Europe. That preoccupation not only caused the War of 1812; it also shaped the course of the war and influenced the terms upon which the British were willing to end it.

Part of a series of articles titled The Global Context of the War of 1812 .

Last updated: February 26, 2015