Last updated: March 2, 2022

Article

Reconnecting Creeks to Culture in Africatown

By Margaret Gach

When a local reporter announced he had found the remnants of the Clotilda, the last known ship to bring African captives to the United States, Africatown, Alabama, native Joe Womack knew the nation would be paying attention.

“What we were doing was already in the news, but when you look up at the morning news and CBS is talking about the Clotilda in Mobile, Alabama, and then you see National Geographic come in with crews, people can’t deny what you’re doing,” Womack said.

Despite the recent national news coverage, Womack had already been working for years with a group of Africatown residents and the National Park Service to reconnect the neighborhood to its abundant natural resources.

A Town with History

On the cusp of the Civil War, when the international slave trade was illegal, 110 Africans were forcibly brought to Mobile, Alabama, on the Clotilda. After the slaves were unloaded, the ship captain tried to hide the Clotilda in Mobile Bay to avoid detection by federal authorities.

After their emancipation, a small group of residents formed Africatown, an independent community established to uphold the linguistic and cultural traditions of their home in West Africa. The residents harvested fruit from trees, hunted for wild hogs in the bayou and fished the three rivers that bound the community for speckled trout.

When an influx of paper mills and other industries capitalized on Africatown’s water resources, the places in which residents went to play, fish and even baptize their children were blocked and polluted by factories, railroads and oil tanks.

According to local Ruth Ballard, Africatown had a population of 12,000 people at its height, in addition to two post offices, a barbershop, grocery stores and restaurants to feed everyone. Since the mills left in the 1990s, the neighborhood now has 2,000 residents, with no gas stations or grocery stores within a five-mile radius.

Connecting History to Community

According to Womack, Africatown has aimed to reconnect the neighborhood and its people to the water in an effort to preserve history and to rebuild the area.

Womack encouraged the Alumni Association of the Mobile County Training School to apply for technical assistance from the National Park Service – Rivers, Trails & Conservation Assistance program after learning from project specialist Liz Smith-Incer that the National Park Service could help create a trail plan to make the water accessible to residents again.

Smith-Incer has worked with the Africatown Connections Blueway planning team and its partners for two years. Prior to the discovery of the Clotilda, Smith-Incer and community members had been working to link the historical neighborhoods and Africatown USA State Park via a water trail following Three Mile Creek, Mobile River and Chickasaw Creek.

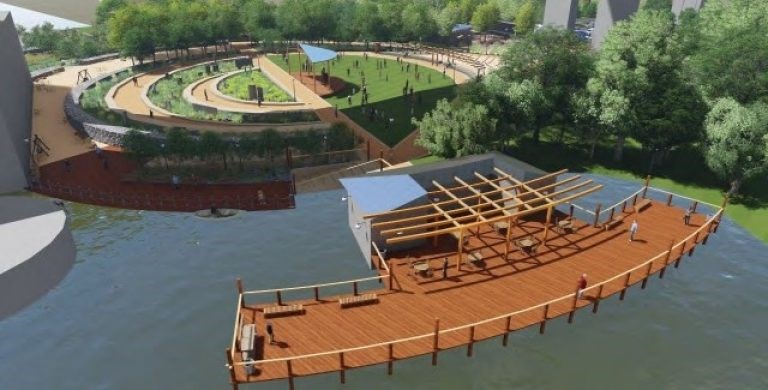

Smith-Incer facilitated collaboration between the Africatown Connections Blueway planning team and Mississippi State University’s Department of Landscape Architecture. The students formulated concept plans for various proposed sites along the water trail. Recommendations included transforming neglected and muddy river access points into kayak and canoe docks with plenty

of safe spaces for fishing and for enjoying the scenery.

Cochrane Africatown USA Bridge, where the Clotilda first landed. Photo by Margaret Gach, National Park Service.

“One of the important values brought [into the planning class] was having students being able to listen – to just listen to people’s stories, and then to be able to interpret those stories,” said Bob Brzuszek, a professor who teaches the class with colleague Chuo Li. “This is, in essence, an interpretive design – one that communicates a culture, communicates the issues in that culture,

communicates the values in that culture – so that those are not forgotten.”

Planning team member Vickii Howell, president and CEO of M.O.V.E. Gulf Coast Community Development Corporation and a native Mobile resident, had never heard Africatown’s history until just a few years ago. Howell is now focused on the project’s potential to attract investors and spur the neighborhood’s economic development.

"What we’re doing really not only affects the lives of people, but the environment.” – Joe Womack

“If we can take this story, take these plans, and turn them into something that can be an economic basis, it will transform everything that we have in this community,” Howell said. “Every part of the project includes opportunities for business growth in the community, including boating services and restaurants for visitors. I love the [Mississippi State University] plan because it’s so concrete, and it’s something people can be a part of.”

When it was time to unveil the plans in June, the community gathered by the site where the Clotilda landed in 1860. Though itis now a patch of dirt and overgrown bushes, the team hopes to build piers with picnic tables and a community park. The Africatown Connections Blueway Celebration attracted more than 200 residents who were all asked by the organizers for their permission to move ahead with the plans. According to Womack, not only was the consent enthusiastic, but there was much “oohing and aahing” when the concept designs were shown.

Looking Ahead

“What we’re doing really not only affects the lives of people, but the environment,” Womack said. “We’re trying to preserve and protect the environment and make it better for the residents here.”

The group is now using the concept plans to apply for grants and assistance to fulfill the team’s promises to the community. Smith-Incer noted that her focus is on building the organizational capacity of the Africatown Connections Blueway palanning team.

“It is really important to the National Park Service that when we leave a project, the project will be sustainable and [will] flourish for years to come,” Smith-Incer said. “I think we have built a strong relationship between the resources, the city and the state that can be sustained over time.”

While it will take hard work to keep Africatown, its story and its residents at the forefront of the region and the nation’s minds, the planning team and community are confident that their work will inspire others to embrace the history of their own pasts. As a Mobile County Training School student in the 1940s, Ballard said she was never taught the history of the Africans who had founded the school less than a century before.

“My hope and prayer is that it will be taught in schools so that the children will know the history of our area,” Ballard said. “Not just the children at Mobile County Training School, but the entire world.”