In the second year of the Civil War, Northern hopes were again raised for a quick victory. However, Union Gen. George B. McClellan made little progress beginning a spring campaign in 1862, resulting in a restless public and press. Finally forced into action, McClellan decided to move his massive Army of the Potomac by water to Fortress Monroe in Virginia and from there advance up the James River Peninsula to take the Confederate capital of Richmond.

"Must be suppressed." Confederate General Lee, talking about Union General Pope

1862 - The Peninsula Campaign

Library of Congress

Gathering a force of some 63,000 men around Richmond, Confederate Gen. Joseph E. Johnston determined to stop the approaching Federals. On May 31st, in the two day Battle of Seven Pines, also known as the Battle of Fair Oaks, the Confederates were repulsed, and Johnston was severely wounded, but McClellan was delayed and unable to take Richmond. Command of the Army of Northern Virginia was then given to Gen. Robert E. Lee. Within two weeks, Lee strengthened the defenses of Richmond and the morale of the troops greatly improved.

By June 25th, Lee had assembled a force of about 90,000 men, including Gen. Thomas "Stonewall" Jackson's victorious command, newly arrived from the Shenandoah Valley. The next day, with trusted generals and determined troops, Lee launched a great counteroffensive. In a series of desperately contested operations, known as the Seven Days' Battles, McClellan was forced back upon Harrison's Landing on the James River, losing all the ground he had gained. Though the campaign was costly in Confederate casualties, Lee saved Richmond and cloaked his army with a sense of invincibility.

While fighting raged near Richmond, on June 26th a new Union army was created from three separate commands that had been previously operating independently in northern Virginia. Maj. Gen. John Pope was assigned to command this new force, christened the "Army of Virginia."

By mid-July, Pope's new army was beginning to take shape and move southward across Virginia. Even though McClellan's huge army remained at Harrison's Landing and the movement would weaken Richmond's defenses, on July 13th, Lee dispatched Jackson's wing of the army north to confront Pope and protect the vital railroad junction at Gordonsville. Lee remained with the other wing, under the command of Gen. James Longstreet.

On August 3rd, McClellan received orders from Washington to abandon the Peninsula and join forces with Pope. Reluctant to do so, McClellan slowly and incrementally began moving his army by water. The movement of Union troops at Hampton Roads caught the eye of a recently captured Confederate cavalry officer who was being exchanged. Upon his release and arrival in Richmond on August 5th, John S. Mosby reported his observations to Lee. It became evident that McClellan no longer posed any immediate threat to Richmond. This opened an opportunity for Lee to concentrate his entire army against John Pope.

Taking the War to the People

National Archives and Records Administration

As Pope led his army deeper into Virginia, he introduced a series of general orders that many found shocking. Up until this point, the armies had sought to conduct the war in such a way as to protect civilians and do little harm to property. To Pope, this "velvet-footed advance" was counter-productive. He wanted to intimidate and defeat not just the Confederate army, but the Southern people as well.

Pope's orders dictated that local civilians could be held liable for damage done by Confederate partisans. He demanded oaths of loyalty from male civilians within Union lines. Pope also permitted his men to live off the land, requisitioning food and supplies from the farms and towns they passed.

To Confederate leaders, this approach to war was vile and dishonorable. Upon hearing of Pope's methods, Lee himself called Pope a "miscreant" and declared that he "must be suppressed."

Cedar Mountain

NPS

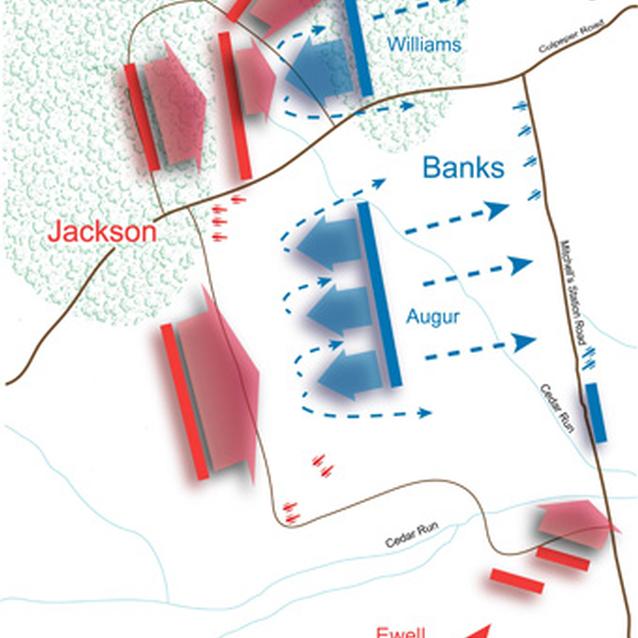

While McClellan was moving his army back to Washington, Jackson saw an opportunity to strike Pope as he was trying to concentrate the three corps of his army near Culpeper, Virginia. Crossing the Rapidan River, Jackson moved north and on August 9th clashed with Pope's 2nd Corps under Nathaniel Banks at Cedar Mountain, five miles south of Culpeper. Jackson's command, strengthened by Gen. A.P. Hill's Light Division, severely pressed the Union lines. However, the timely arrival of Union reinforcements from Irvin McDowell's 3rd Corps late in the day forced Jackson to withdraw back across the Rapidan. The Confederates suffered 1,276 casualties in the fighting and intense heat at Cedar Mountain. Union losses totaled 2,381 killed, wounded and missing.

Part of a series of articles titled The Vortex of Hell.

Next: Union Command Trouble

Last updated: February 3, 2015