Last updated: October 15, 2021

Article

Field School at Prince William Forest Park: Documenting Cabin Camps

The CESU Agreement

During the summer of 2018, four students from the University of Mary Washington participated in a field school to document two cultural landscapes at Prince William Forest Park: Cabin Camp 4 and Cabin Camp 2. The field school was coordinated by Michael Spencer, Associate Professor & Director of the Center for Historic Preservation at the University of Mary Washington, the Cultural Landscapes Program staff of the National Park Service National Capital Region (NCR), and park staff.

NPS / National Capital Region

The partnership was established through a Cooperative Ecosystem Studies Unit (CESU) agreement. CESUs provide research, technical assistance, and education to federal land management and environmental agencies and their partners. The field school was the pilot effort of this type for the National Capital Region Cultural Landscapes Program (CLP). It was modeled after the Acadia Field School that was managed by the Olmsted Center for Landscape Preservation and modified to meet the needs and resources of the park and the region.

The NCR was committed to finding a field school method that worked for both the National Park Service and the University of Mary Washington. As the project developed, the partners adjusted processes and protocols in response to what worked and what didn't. The outcomes of these decisions and the lessons learned by the CLP staff, UMW faculty, and students shaped the 2019 field school and will serve as a model for future iterations of the field school.

The Field School

Starting in June of 2018, two juniors, one senior, and one graduate student arrived at the Prince William Forest Park, located about 35 miles south of Washington, DC. The students were at different stages in historic preservation and GIS programs, so they brought varying experience in landscape assessment.

NPS / National Capital Region

In the second session, the students reviewed notes and photographs from their initial documentation of Cabin Camp 2 as they documented the second site, Cabin Camp 4. The practice helped them to compare the Cabin Camps and the possible reasons for their similarities and differences.

They used GPS equipment to document Cabin Camp 2 in a third session, producing a geo-referenced map of the site and connecting the forms of documentation they had practiced throughout the field school. Field work continued for several additional weeks.

The documentation will be used to complete CLI reports for Cabin Camp 2 and Cabin Camp 4 at Prince William Forest Park. The CLI identifies, documents, and evaluates all historically significant park cultural landscapes and their features and is an important tool for continued documentation and management of park cultural landscapes.

The Rustic Style Camps

Prince William Forest Park preserves one of the largest parcels of undeveloped land in the National Captial Region. The park’s natural landscapes also speak of its rich cultural history. The cabins camps were developed as part of the Recreational Demonstration Area (RDA) program, when the park opened as a summer camp for children of nearby Washington, DC.

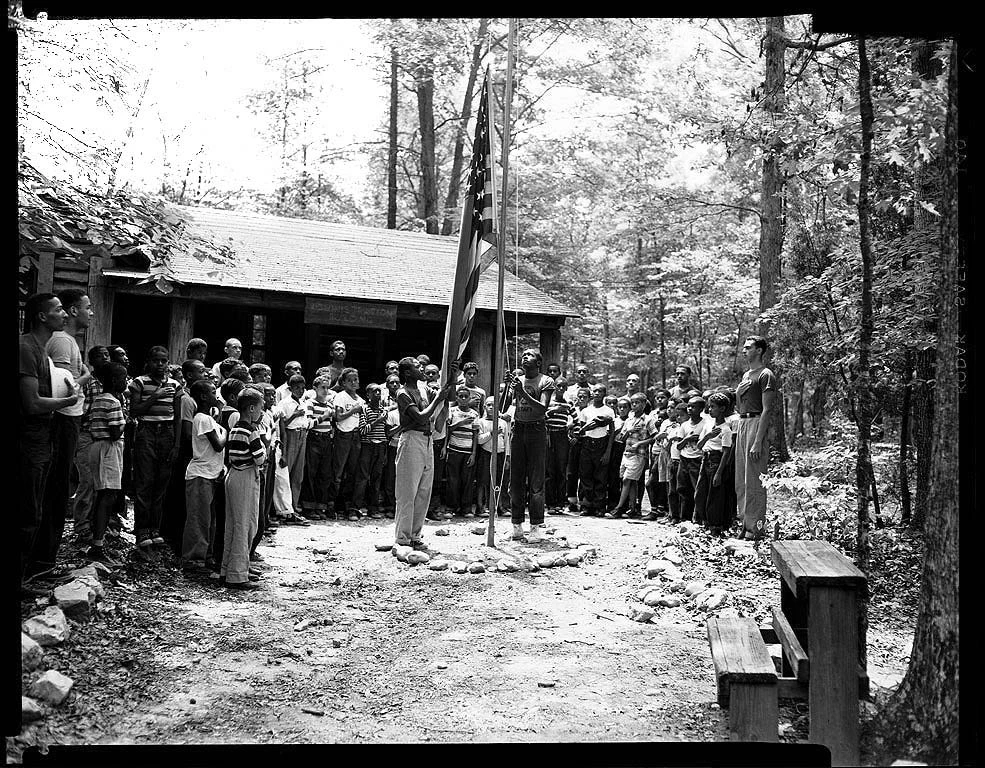

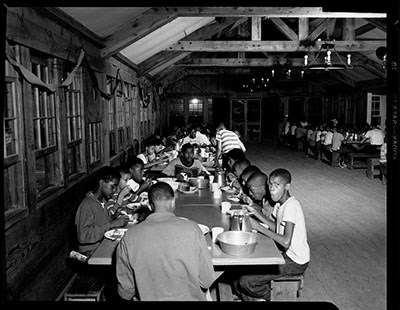

Photo courtesy: Scurlock Studios, Archives Center, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution

Over a period of seven years, more than 2000 young men in Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) companies developed the Chopawamsic RDA (later renamed Prince William Forest Park). They built the five cabin camps, created swimming and recreation lakes, and created many of the roads, trails, and bridges that are still used throughout the park today. Many of the materials they used in construction were found or made within the park, including wood and stone, a portable sawmill, and an on-site blacksmith shop.

While the labor was supplied by the CCC, the landscape and structural designs were attributed to Works Progress Administration architects and engineers. The Rustic style expressed in the public recreational architecture at Chopawamsic RDA is distinctive to this period (1933-1942).

Photo courtesy: Scurlock Studios, Archives Center, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution

When the Chopawamsic RDA opened in 1936 as a summer camp for children of Washington DC, it was the fourth largest of the 46 RDAs created across the nation. Organizations in the capital worked with the NPS to sponsor camps for children and families of different backgrounds. Each of the cabin camps had a slightly different character depending on the organizations that used it. The historic use of each camp also illustrates the impact of segregation in the park’s development. Two of the five cabin camps at the Chopawansic RDA were operated for African American children and families, including Cabin Camp 4.

Cabin Camp 1 Cultural Landscape Inventory, Prince William Forest Park

Prince William Forest Park Historic District, National Register of Historic Places

Mawavi Historic District, Chopawamsic RDA Camp 2, National Register of Historic Places

Pleasant Historic District, Chopawamsic RDA Camp 4, National Register of Historic Places

Prince William Forest Park website

Good, Albert. Park and Recreation Structures, Part I-III. Washington, DC: United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 1938.

Prince William Forest Park Historic District, National Register of Historic Places

Mawavi Historic District, Chopawamsic RDA Camp 2, National Register of Historic Places

Pleasant Historic District, Chopawamsic RDA Camp 4, National Register of Historic Places

Prince William Forest Park website

Good, Albert. Park and Recreation Structures, Part I-III. Washington, DC: United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 1938.