Last updated: June 24, 2021

Article

Protesting to Keep Farming in the Hole-in-the-Donut

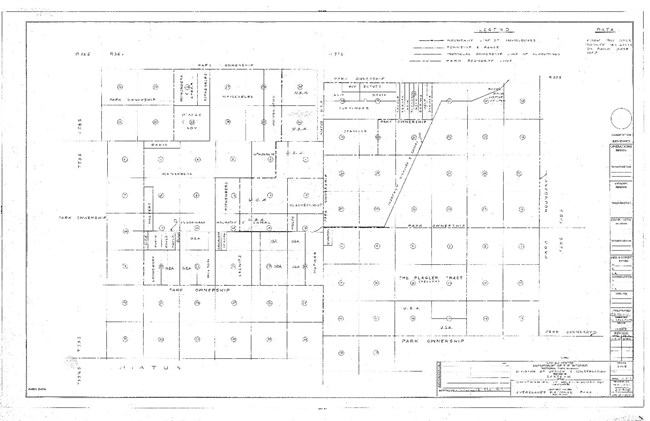

NPS (EVER 01847.006)

This area was used for agriculture from the 1940s to 1975 and farmers implemented a technique to work the inhospitable soil called rock plowing. This technique required farmers to grind up the limestone bedrock and mix it with the thin soil layer above; something that was done multiple times to create deeper soil conducive to the growth of winter vegetables like tomatoes.

Farmland in the HID was leased out to multiple farming operations and among them was the prominent Iori family. In 1946 brothers Peter and Tony Iori began to farm in the HID and purchased the land in 1955. The farmer’s use of herbicides and pesticides to maintain their crops concerned the park because their effects of pesticides could impact wildlife outside the HID.

Over the years the relationship between park personnel and the Iori family became tense due to disputes over boundaries, incidents of criminal activity, and because each had different visions of how the land should be used.In order to fulfill its mission of preserving the park for future generations, the park began to explore options to purchase and restore HID land. When the Iori farmland fell under bankruptcy in 1962, discussions with the park began shortly thereafter and it was determined “that [the] Iori's should be permitted to continue to lease fro the coming agricultural season on the basis that should lands become available for the Park, the lease would then be cancelled at the end of the season."

NPS

Leading up to the 1970s the park slowly began to purchase HID land from the farmers and by 1974 it had purchased all but 44 acres in the HID. Park leasing of lands for agricultural production continued until June 1975 when all leasing ceased. Plans for land restoration work would begin in the HID in 1989.

As the deadline to vacate the farmlands approached, protests led by the South Florida Tomato and Vegetable Growers, Inc. were organized to support continued farming operations in the HID. The organization claimed that farming in the HID added $25 million to the local economy and provided seasonal employment for 3,000 migrant workers, many of whom were from Mexico.

Farm laborers felt that the desire to enlarge the park and protect animals outweighed their need to earn a livelihood. To help their cause they brought in EcoImpact, Inc. to study the ecological impact of agriculture and make recommendations.

Their report concluded that farming in the Hole-in-the-Donut had not only “minimal” effect on wildlife, but that farming was needed to end the “period of reduced food production” caused by “adverse climate, arable land shortages, and a reduction in the skilled farmer.” It also offered 5 different alternatives for the park that would allow for the continuation of farming. Park managers believed the report was full of errors “designed to support a preconceived conclusion that farming should continue,” and held fast to its position that agriculture in the Hole-in-the-Donut was incompatible with the park’s purposes.

NPS (EVER 01847.003)

While farming is not practiced in the park today, the park is surrounded by the agricultural land and serves as a daily reminder of the Iori farm protests of 1975.

By Melissa Kocelko