Part of a series of articles titled Eisenhower and the Nuclear Arms Race in the 1950s.

Previous: “Project Solarium”

Next: The Shock of Sputnik

Article

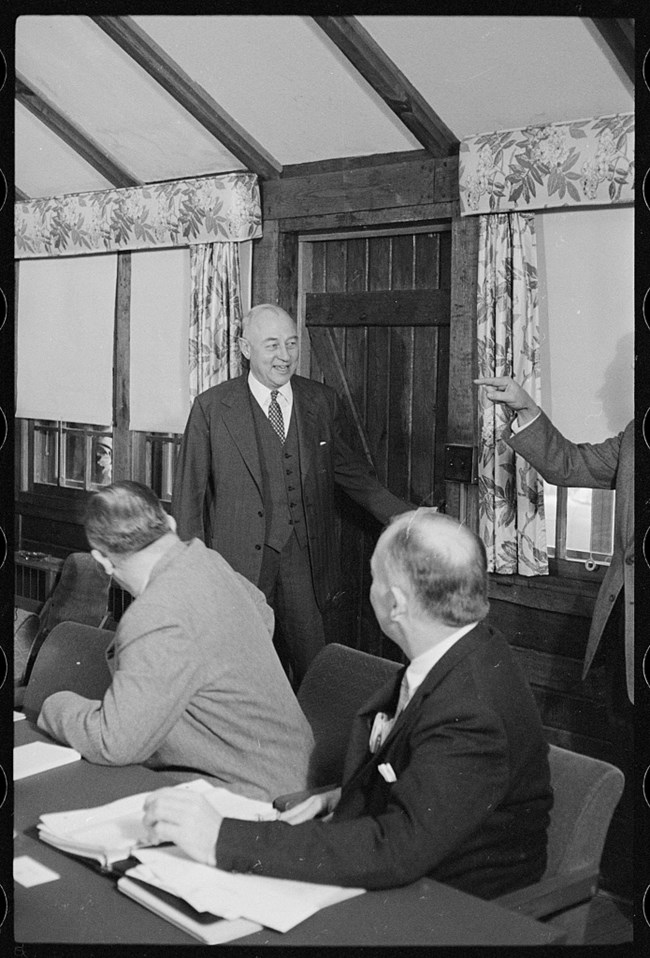

Library of Congress

Massive retaliation limited the Eisenhower administration’s policy options. The 1954 Dien Bien Phu crisis in Vietnam, for example, demonstrated the limitations of too great a reliance on the nuclear response. Since 1945 the United States had supported France’s efforts to defend its colonial presence in Indochina, both militarily and economically, and in 1953, France and the United States adopted the Navarre Plan to prevent the Communist-led Viet Minh takeover of the region. That same year French General Henri Navarre established a military base at Dien Bien Phu in northwestern Vietnam in hopes of luring the Viet Minh into battle. The Viet Minh laid siege on the French and a standoff occurred, with the United States airlifting supplies to the French.

Many of Eisenhower’s advisors, including National Security Council (NSC) Chairman Admiral Arthur Radford, believed the only way to save the French was by dropping atomic bombs on their opponents. Eisenhower rejected this suggestion, arguing that nuclear weapons were too destructive to use in a limited conflict, and perhaps too politically damaging to use at all. “You boys must be crazy,” he said. “We can’t use those awful things against the Asians for the second time in ten years. My God.” Without support from either American ground forces or nuclear weapons, the French garrison fell to the Viet Minh on 7 May 1954.

The decision not to use nuclear weapons in Vietnam called into question the administration’s policy of massive retaliation and deterrence. Massive retaliation might have been a successful policy for keeping the Cold War in balance and an option for stopping a major Soviet advance into Western Europe–although it was never put to this test–but it did not answer everything. If the administration was not ready to use nuclear weapons in all situations, Eisenhower’s strategists reasoned, other options needed to be available to American leaders. Ironically, at an earlier time, Eisenhower had publicly stated that nuclear bombs were like any weapon, and could be “used just exactly as you would a bullet or anything else.” In private, however, the president and his top advisors were each beginning to doubt the wisdom and utility of relying solely on the atomic threat. Despite their concerns, Soviet developments would soon prompt the United States to continue and even to expand its nuclear capabilities.

Part of a series of articles titled Eisenhower and the Nuclear Arms Race in the 1950s.

Previous: “Project Solarium”

Next: The Shock of Sputnik

Last updated: October 20, 2020