Last updated: May 17, 2023

Article

President Lincoln's Cottage: A Retreat (Teaching with Historic Places)

(Courtesy of President Lincoln's Cottage, a National Trust Historic Site)

A cool breeze whispers by a picturesque cottage perched on a hill overlooking the city of Washington. A tall man in a dusty black suit gallops up the path and halts his horse in front of the house. He breathes in the country air and exhales a soft sigh of relief. Here, surrounded by open green spaces and a few stately buildings, the man has found a place to relax. It seems difficult to believe that such a place is only three miles from the dust and noise at the center of the nation’s capital. The weary man in the dark suit is none other than President Abraham Lincoln and this is his seasonal home, his refuge from the chaos of Civil War Washington, DC. Yet there are decisions to be made and responsibilities from which he cannot escape.

President Lincoln and his family resided in this cottage from June through November of 1862, 1863 and 1864. Lincoln’s first visit was a few days after his inauguration and his last visit was the day before his assassination. While in many ways it served as a sanctuary for Lincoln, he was still consumed by his presidential responsibilities. Each day on his commute to the cottage, the President passed contraband camps (temporary shelters built to house the thousands of former slaves that escaped to freedom behind Union Army lines), ambulances carrying sick soldiers to and from nearby hospitals, and cemeteries, all sights that served as reminders of the Civil War. While at this retreat, Lincoln met with both friends and political opponents and discussed strategies for winning the war. Most notably, he formulated his thoughts on emancipation and issued the Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation.

About This Lesson

This lesson is based on the National Register of Historic Places nomination file, “U.S. Soldiers and Airmen’s Home” (with photographs) and materials from the President Lincoln’s Cottage historic site. Made possible through the sponsorship of President Lincoln’s Cottage and the National Trust for Historic Preservation, this lesson was written by Jodi Boyle, Craig MacDonald, and Emily Weisner, graduate students in Public History at American University, with assistance from staff of the National Trust for Historic Preservation. The lesson was edited by staff of the National Trust and the National Park Service’s Teaching with Historic Places (TwHP) program and TwHP intern Leah Suhrstedt, an American University graduate student. This lesson is one in a series that brings the important stories of historic places into classrooms across the country.

Where it fits into the curriculum

Topics: This lesson could be used in teaching units on President Abraham Lincoln, the Civil War, slavery and emancipation, and Washington, DC

Time period: Mid-19th Century

Objectives for students

1) To describe the impact of the Civil War upon Washington, DC and on President Lincoln.

2) To explain the importance of the work Lincoln did at his retreat.

3) To compare and contrast President Lincoln’s formal, public life at the White House with his more informal, private life at his seasonal retreat at the Soldiers’ Home.

4) To analyze the provisions of the Emancipation Proclamation.

Materials for students

The materials listed below can be used directly on the computer or can be printed out, photocopied, and distributed to students. The maps and images appear twice: in a smaller, low-resolution version with associated questions and alone in a larger version.

1) One map of President Lincoln’s commute route from the Soldiers’ Home to the White House;

2) Three readings related to Lincoln's time at the Soldiers' Home, the strain of the war on the President, the Emancipation Proclamation, and Mary Todd Lincoln’s views of the Soldiers’ Home;

3) five images of President Lincoln and Civil War Washington.

Visiting the site

President Lincoln’s Cottage is located at the intersection of Upshur St., NW, and Rock Creek Church Rd., Washington, DC, on the grounds of the Armed Forces Retirement Home, which owns the building. The cottage was extensively restored by the National Trust for Historic Preservation, which operates the building and offers public tours. For more information, please contact President Lincoln’s Cottage at AFRH-W Box 1315, 3700 North Capitol Street NW, Washington, DC 20011-8400, or visit President Lincoln’s Cottage Website.

Getting Started

Inquiry Question

Are there any buildings you might describe as a “cottage”? Why or why not?

Setting the Stage

|

In November 1860 Abraham Lincoln won a highly contested presidential election in a nation on the brink of war. Perceiving Lincoln as a threat because of his opposition to slavery, southern states began seceding in January 1861. In April 1861, not long after his March inauguration, the Civil War began. The North (the Union) and the South (the Confederacy) entered into a conflict over multiple issues, with states’ rights and slavery among the most hotly debated. Although both sides thought it would be a short war, it lasted four long years, finally ending in April 1865. During the conflict, the Union Army lost over 300,000 men and the Confederacy suffered over 250,000 deaths. This was approximately 20% of the country’s population at the time and today would be equivalent to five to six million people. The fighting, destruction, and death took a toll on both President Lincoln and the country. |

Locating the Site

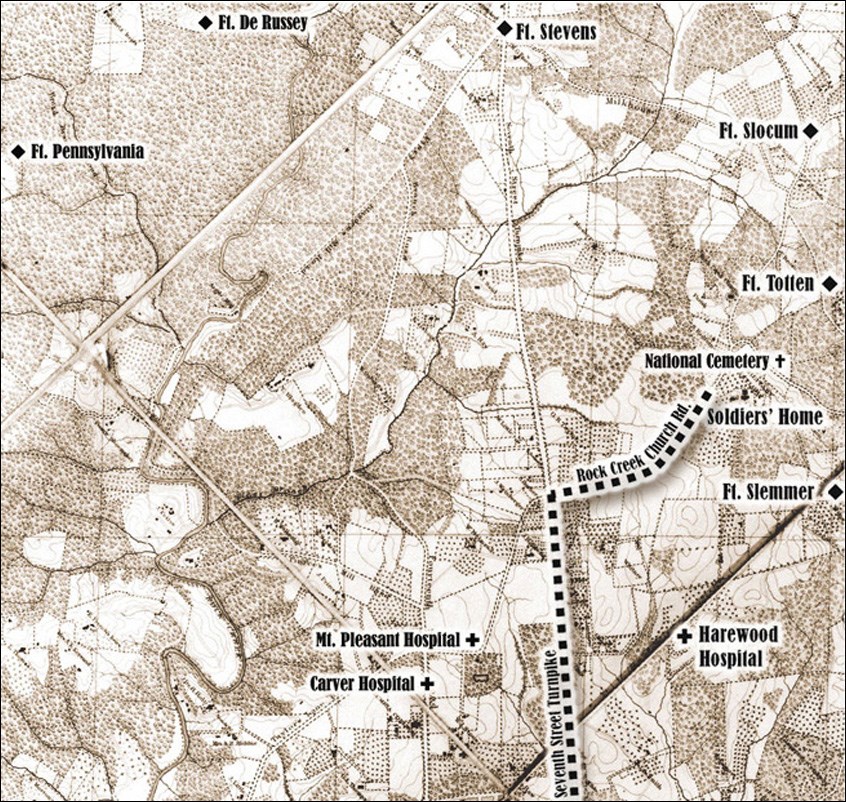

Map 1a: Lincoln's Commute from the White House to the Soldiers' Home: northern portion.

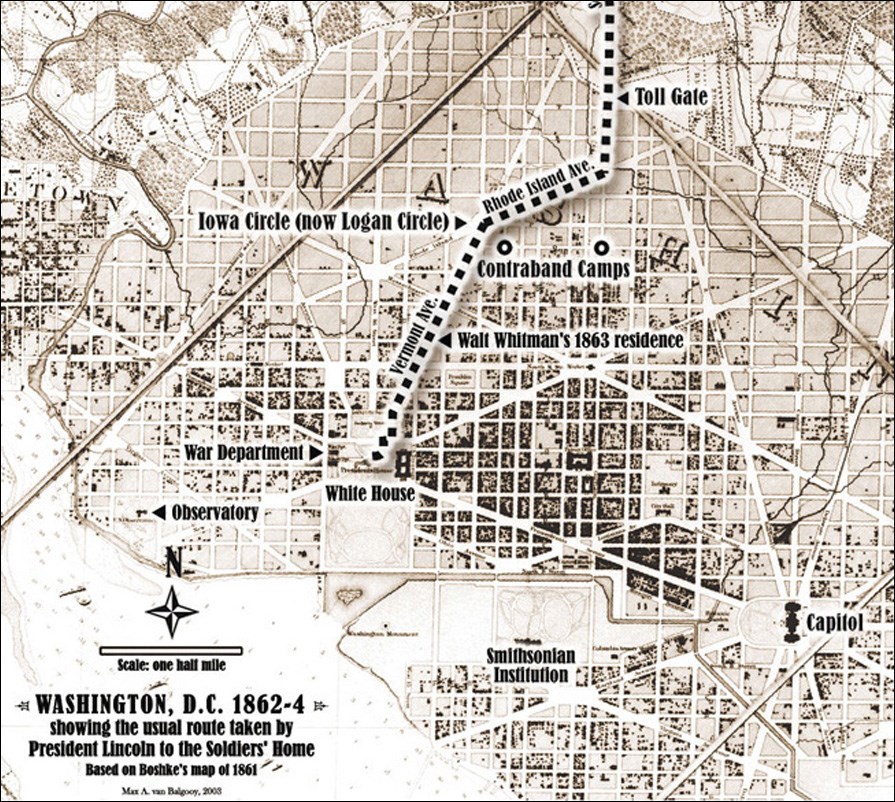

Map 1b: Lincoln's commute from the White House to the Soldiers' Home: southern portion.

President Abraham Lincoln and his family spent the summers of 1862, 1863, and 1864 living in a cottage on the grounds of the Soldiers’ Home, a home for elderly and disabled army veterans. Even when he was staying at the cottage, President Lincoln commuted to and from the White House every day, either on horseback or in a carriage, escorted by soldiers for protection. During his commute, President Lincoln passed many sites that reminded him of the ongoing Civil War.

Please note: On Map 1a, the diagonal lines not labeled as streets are folds on the original map. On Map 1b, the two diagnoal lines forming a point at the top of the page also show folds on the original map.

Questions for Map 1a and 1b

1. Trace the route that Lincoln traveled between the White House and the Soldiers’ Home. What types of places did Lincoln pass? Based on the map scale in the lower left corner of Map 1b, what was the distance between the Soldiers’ Home and the White House? How many miles did Lincoln ride from the White House before he left the city? (Hint: the toll gate marks the edge of the city.)

2. How long might Lincoln’s commute have taken by horseback, assuming that his horse traveled at about 6 miles an hour? At www.wmata.com, use the trip planner to find out how long the same trip would take today via public transportation. The White House street address is 1600 Pennsylvania Ave, NW and the Soldiers’ Home is at the intersection of Rock Creek Church Rd. and Upshur St., NW.

3. On Map 1b, locate the contraband camps (which were temporary shelters built to house the thousands of former slaves that escaped to freedom behind Union Army lines). These usually were built in great haste, overcrowded and unsanitary. Lincoln probably could see the closest one to his route. How do you think he would have felt as he passed it? What people or places do you pass on your way to school? What do they make you think about?

4. Find the Seventh Street Turnpike. This was one of the main routes into Washington from the North. How do the locations of forts built to protect the city during the Civil War relate to the Seventh Street Turnpike? Why might that be the case? How close are they to the Soldiers’ Home?

5. Find a map of Washington, DC today in an atlas or online. What streets did Lincoln travel on the historical map? Can you find those same streets on the current map? Compare the two maps. What has changed? What has stayed the same?

Determining the Facts

Reading 1: President Lincoln at the Soldiers' Home

Only three miles from the White House, the Soldiers’ Home was created in 1851 as a home for retired or disabled enlisted soldiers. The cottage where the Lincoln family lived during the warmer months of 1862, 1863, and 1864 was built in 1842 as the summer house of George Washington Riggs, a prominent banker. In 1851, Riggs sold the property to the federal government, and that same year, Congress passed legislation that established the Soldiers’ Home as a place for retired or disabled soldiers.

The Soldiers’ Home was President Lincoln’s retreat from the White House. Considered “rural” at the time, the higher elevation of the Soldiers’ Home offered pleasant breezes and was an escape from the heat and humidity of the city summers. Washington was overcrowded with soldiers, businessmen, and fugitive slaves flocking to the city. Troops were drilling at all hours of the day and night. As a result of the population explosion, the water was polluted and disease was a constant threat.

President Lincoln first visited the Soldiers’ Home a few days after his inauguration. During the Lincolns’ time at the Soldiers’ Home, the president would have shared the grounds with approximately 200 residents who lived in the dormitory next to the cottage, the presidential guard camped on the grounds, and the officers who managed the retirement home and lived in houses on the property. When standing at the front door of the cottage, the president would have been able to see graves multiply in the Soldiers’ Home National Cemetery, and from the veranda on the south side of the cottage, he would have been able to see the Washington Monument and the Capitol dome, both of which were unfinished at the time.

President Lincoln’s wife, Mary Todd Lincoln, and their two sons, Robert and Tad, also spent time at the cottage at the Soldiers’ Home. A third son, Willie, died in February 1862 due to drinking bad water and contracting what was likely typhoid. Mary Lincoln was devastated by her son’s death and wore mourning dress (black clothes) for a full year, not uncommon in the Victorian era. During his father’s presidency, Robert Lincoln attended Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts, while Tad lived with his parents. While staying at the cottage, the Lincolns enjoyed the relaxed atmosphere of the Soldiers’ Home. On July 26, 1862, Mary Lincoln wrote a letter to a friend, Fanny Eames, from the Soldiers’ Home. “We are truly delighted with this retreat, the drives & walks around here are delightful, & each day, brings its visitors. Then too, our boy Robert is with us, whom you may remember. We consider it a ‘pleasant time’ for us, when his vacations, roll around, he is very companionable, and I shall dread when he has to return to Cambridge. I presume you will not return to W.[ashington] before cool weather, thus far we have found the country very delightful.1 After Lincoln's assassination, Mary Lincoln reflected, “How dearly I loved the ‘Soldiers’ Home’ and how little I supposed, one year since, that I should be so far removed from it."2

Another view of the Lincoln family at the Soldiers’ Home comes from Albert See, a member of the presidential guard stationed at the White House and Soldiers’ Home during the Civil War. He was a soldier in Company K of the 150th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry. In his autobiography, Albert See recollected, “When at the Soldiers’ Home one bright moonlight night, the president and Tad were playing checkers on the porch and as the sentinel passed by the president asked him if he ever played checkers and the sentinel said he did and the president said, “Set down your gun and come up with us, take a game.” He did so and said he did his best but was badly beaten."3

However, even though he was living at the Soldiers’ Home during the summertime, Lincoln kept up with his presidential duties. He commuted daily to the White House, passing hospitals and contraband camps on his way. He also conducted business at the cottage, holding meetings and welcoming visitors, including political opponents. President Lincoln could also reflect on the progress of the war and formulate major decisions. One of the biggest decisions of his presidency was to issue the Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863, which symbolically changed the course of the war. The president issued the Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation on September 22, 1862 while living at his seasonal retreat, indicating the course of action he planned to pursue regarding slavery.

It is believed that Abraham Lincoln visited the cottage for the last time on April 13, 1865.4 The Lincolns planned to spend the upcoming summer season at the cottage, their first without an ongoing war. Their plans were dashed when actor John Wilkes Booth assassinated President Lincoln the next day, April 14, 1865, in Washington, DC, as the president and his wife enjoyed a play at Ford’s Theater.

1Mary Todd Lincoln to Mrs. Charles (Fanny) Eames, July 26, 1862 in Justin G. Turner and Linda Levitt Turner, eds., Mary Todd Lincoln: Her Life and Letters (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1972), 130-31.

2Matthew Pinsker, Lincoln’s Sanctuary: Abraham Lincoln and the Soldiers’ Home (New York: Oxford University Press, 2003), 183.

3Albert N. See, Autobiography of Albert Nelson See with an introduction by Joseph S. Northrop (originally published by author 1921; Huntington, Ind.: Joseph S. Northrop, 1983), Henry Horner Lincoln Collection, Illinois State Historical Library, Springfield, Ill.

4Pinsker, 204.

Questions for Reading 1

1. Look up the word “retreat”-- what is the definition? Why do you think Lincoln needed a retreat?

2. How did President Lincoln spend his time at the Soldiers’ Home?

3. Who were the primary residents of the property and how many were here during Lincoln’s time? How do you think the presence of retired and disabled soldiers would have affected the Lincoln family?

4. How did Mary Lincoln feel about living at the cottage at the Soldiers’ Home? What adjectives or words did Mary Lincoln use to describe life at the cottage?

5. Based on Mrs. Lincoln’s letter to Mrs. Charles (Fanny) Eames letter, how might you describe the Lincoln family’s private life at the cottage? How does it compare with the ways that you and your family or friends spend time together?

6. What is your impression of Lincoln based on his behavior toward the soldier in the See story? How does this story support that impression?

Reading 1 is adapted from Justin G. Turner and Linda Levitt Turner, eds., Mary Todd Lincoln: Her Life and Letters (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1972); Matthew Pinsker, Lincoln’s Sanctuary: Abraham Lincoln and the Soldiers’ Home (New York: Oxford University Press, 2003); Albert N. See, Autobiography of Albert Nelson See with an introduction by Joseph S. Northrop (originally published by author 1921; Huntington, Ind.: Joseph S. Northrop, 1983).

Determining the Facts

Reading 2: Walt Whitman and President Lincoln

Walt Whitman was a poet who first came to Washington during the Civil War looking for his injured brother. He stayed and continued to care for wounded soldiers at area hospitals. He lived in a house at the intersection of Vermont Avenue and L Street and often witnessed President Lincoln riding by on his way to or from the cottage. Below is an excerpt from his journal, written on August 12, 1863.

I see the President almost every day, as I happen to live where he passes to or from his lodgings out of town. He never sleeps at the White House during the hot season, but has quarters at a healthy location some three miles north of the city, the Soldier's Home, a United States military establishment. I saw him this morning about 8:30, coming in to business, riding on Vermont Avenue, near L Street. He always has a company of twenty-five or thirty cavalry, with sabers drawn and held upright over their shoulders. They say this guard was against his personal wish, but he lets his counselors have their way. The party makes no great show in uniform or horses. Mr. Lincoln on the saddle generally rides a good-sized, easy-going gray horse, is dressed in plain black, somewhat rusty and dusty, wears a black stiff hat, and looks about as ordinary in attire, etc., as the commonest man. A lieutenant, with yellow straps, rides at his left, and following behind, two by two, come the cavalry men, in their yellow-striped jackets. They are generally going at a slow trot, as that is the pace set them by the one they wait upon. The sabers and accoutrements clank, and the entirely unornamental cortège [the group following and attending to some important person] as it trots toward Lafayette Square arouses no sensation, only some curious stranger stops and gazes.

I see very plainly ABRAHAM LINCOLN'S dark brown face, with the deep-cut lines, the eyes, always to me with a deep latent sadness in the expression. We have got so that we exchange bows, and very cordial ones. Sometimes the President goes and comes in an open barouche [horse-drawn carriage]. The cavalry always accompany him, with drawn sabers. Often I notice as he goes out evenings - and sometimes in the morning, when he returns early - he turns off and halts at the large and handsome residence of the Secretary of War, on K Street, and holds conference there. If in his barouche, I can see from my window he does not alight, but sits in his vehicle, and Mr. Stanton comes out to attend him. Sometimes one of his sons, a boy of ten or twelve, accompanies him, riding at his right on a pony. Earlier in the summer I occasionally saw the President and his wife, toward the latter part of the afternoon, out in a barouche, on a pleasure ride through the city. Mrs. Lincoln was dressed in complete black, with a long crape veil. The equipage [a carriage and all that attends it, such as horses and servants] is of the plainest kind, only two horses, and they nothing extra. They passed me once very close, and I saw the President fully, as they were moving slowly, and his look, though abstracted, happened to be directed steadily in my eye. He bowed and smiled, but far below his smile I noticed well the expression I have alluded to. None of the artists or pictures has caught the deep, though subtle and indirect, expression of this man's face. There is something else there. One of the great portrait painters of two or three centuries ago is needed.

Questions for Reading 2

1. Locate Whitman’s home on Map 1b. Based on that and the reading, do you think Whitman would have been very close as Lincoln drove or rode past?

2. Using your own words, how does Walt Whitman describe President Lincoln?

3. Why do you think Whitman would say that Lincoln had a “deep, latent sadness in his expression?” Can you find other examples in the writing that support this statement?

4. How does Whitman’s description of President Lincoln and his traveling companions compare to the travel of today’s presidents? Why was Lincoln accompanied by soldiers with their sabers drawn? How have transportation methods changed? Are there any similarities?

5. Whitman greatly admired Lincoln. Read over the poem, “Oh, Captain, My Captain” that Whitman wrote after Lincoln’s death. After reading this poem, describe Whitman’s feelings about Lincoln. How do you think these feelings might have affected his description in the journal entry above?

Reading 2 is quoted from Walt Whitman, “Abraham Lincoln,” No. 45 (August 12, 1863), Specimen Days in Prose Works (Philadelphia: David McKay, 1892; http://www.bartleby.com/229/1045.html).

Determining the Facts

Reading 3: The Emancipation Proclamation

On September 22, 1862, while living at the Soldiers’ Home, President Lincoln issued the Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation, which announced his intention to free the slaves in Confederate states. Lincoln was working on the Emancipation Proclamation during his first summer at the Soldiers’ Home. The cottage offered Lincoln a place to reflect and think through his ideas on emancipation. He also had the opportunity to discuss ideas with visitors and guests to the Soldiers’ Home.

Lincoln noted that, “I put the draft of the Proclamation aside, waiting for a victory. Well the next news we had was of Pope’s disaster at Bull Run. Things looked darker than ever. Finally came the week of the Battle of Antietam. I determined to wait no longer. The news came, I think, on Wednesday that the advantage was on our side. I was then staying at the Soldiers’ Home. Here I finished writing the second draft of the Proclamation; came up on Saturday, called the cabinet together to hear it, and it was published the following Monday. I made a solemn vow before God that if General Lee was driven back from Maryland I would crown the result by the declaration for freedom to the slaves.”¹

Excerpts from the final Emancipation Proclamation, issued January 1, 1863:

By the President of the United States of America:

A Proclamation.

…That on the first day of January, in the year of our Lord one thousand eight hundred and sixty-three, all persons held as slaves within any State or designated part of a State, the people whereof shall then be in rebellion against the United States, shall be then, thenceforward, and forever free; and the Executive Government of the United States, including the military and naval authority thereof, will recognize and maintain the freedom of such persons, and will do no act or acts to repress such persons, or any of them, in any efforts they may make for their actual freedom...

Now, therefore I, Abraham Lincoln, President of the United States, by virtue of the power in me vested as Commander-in-Chief, of the Army and Navy of the United States in time of actual armed rebellion against the authority and government of the United States, and as a fit and necessary war measure for suppressing said rebellion, do, on this first day of January, in the year of our Lord one thousand eight hundred and sixty-three, and in accordance with my purpose so to do publicly proclaimed for the full period of one hundred days, from the day first above mentioned, order and designate as the States and parts of States wherein the people thereof respectively, are this day in rebellion against the United States, the following, to wit:

Arkansas, Texas, Louisiana, (except the Parishes of St. Bernard, Plaquemines, Jefferson, St. John, St. Charles, St. James Ascension, Assumption, Terrebonne, Lafourche, St. Mary, St. Martin, and Orleans, including the City of New Orleans) Mississippi, Alabama, Florida, Georgia, South Carolina, North Carolina, and Virginia, (except the forty-eight counties designated as West Virginia, and also the counties of Berkley, Accomac, Northampton, Elizabeth City, York, Princess Anne, and Norfolk, including the cities of Norfolk and Portsmouth), and which excepted parts, are for the present, left precisely as if this proclamation were not issued.

And by virtue of the power, and for the purpose aforesaid, I do order and declare that all persons held as slaves within said designated States, and parts of States, are, and henceforward shall be free; and that the Executive government of the United States, including the military and naval authorities thereof, will recognize and maintain the freedom of said persons.

And I hereby enjoin upon the people so declared to be free to abstain from all violence, unless in necessary self-defense; and I recommend to them that, in all cases when allowed, they labor faithfully for reasonable wages.

And I further declare and make known, that such persons of suitable condition, will be received into the armed service of the United States to garrison forts, positions, stations, and other places, and to man vessels of all sorts in said service.

And upon this act, sincerely believed to be an act of justice, warranted by the Constitution, upon military necessity, I invoke the considerate judgment of mankind, and the gracious favor of Almighty God...

By the President: ABRAHAM LINCOLN

¹Paul R. Goode, The United States Soldiers’ Home (Richmond, Virginia, 1957), 68, as quoted in the “U.S. Soldiers’ and Airmen’s Home” (Washington, DC) National Register of Historic Places Inventory—Nomination Form (Washington, DC: Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 1973).

Questions for Reading 3

1. According to President Lincoln, what gave him the authority to make this proclamation?

2. What did President Lincoln say that “the Executive Government of the United States, including the military and naval authority thereof” will do to aid, “persons so declared free”?

3. What did President Lincoln ask the freed slaves to do? What did he tell them not to do?

4. In what region do the persons declared, “thenceforward, and forever free” live? Why do you think some states were not included in the proclamation? Do you think many of those enslaved were likely to have gained their freedom as a result of this proclamation? Why or why not?

5. Why do you think the Emancipation Proclamation is considered such an important document?

Visual Evidence

Illustration 1: Soldiers' Home, Washington DC.

Buildings in this illustration from left to right: Quarters One, Quarters Two, Lincoln Cottage, Sherman Building.

Questions for Illustration 1

1. How would you describe the Soldiers’ Home? Do you think this looks like a suitable home for retired and disabled soldiers? Why or why not?

2. Why do you think several presidents selected this as their summer retreat?

3. Find Lincoln Cottage in the picture above. How does the cottage differ from other buildings you see? Do any of these fit your image of a cottage? Why or why not?

4. The Soldiers’ Home is a National Historic Landmark, and the National Park Service designated the cottage as the President Lincoln and Soldiers’ Home National Monument. Do you think these buildings deserve this honor (refer to Readings 1 and 3, if necessary)? Why or why not?

Visual Evidence

Photo 1: South side of the White House, ca. 1861.

Photo 2: South side of the cottage, from Mary Todd Lincoln's photo album.

Questions for Photos 1 & 2

1. Examine both buildings in the photographs, paying close attention to the size of each building, the design, and other features, such as the number of windows or chimneys. Notice that neither photograph illustrates the “front” side with the main entrance doors. How are these residences similar or different? Which is the more formal home? Which do you think looks more comfortable? How can you tell?

2. Based upon these photographs, in which house do you think you would prefer to live and why?

3. Locate both houses on Map 1a and 1b. How do you think a city house would differ from a country house? How do you behave in different places, such as a friend’s house, your grandparents’ house, at school, or at a job? Do you think you would behave differently in each of the pictured houses? Why or why not?

Visual Evidence

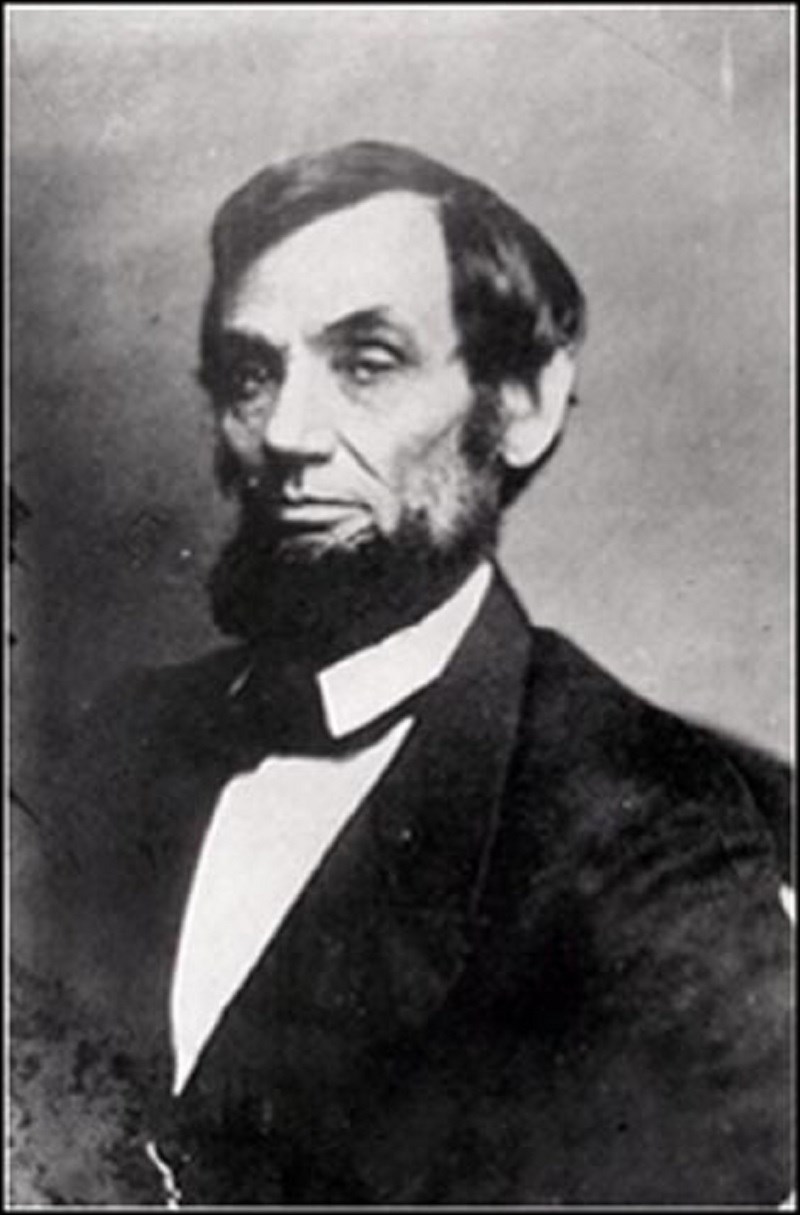

Photo 3: Abraham Lincoln.

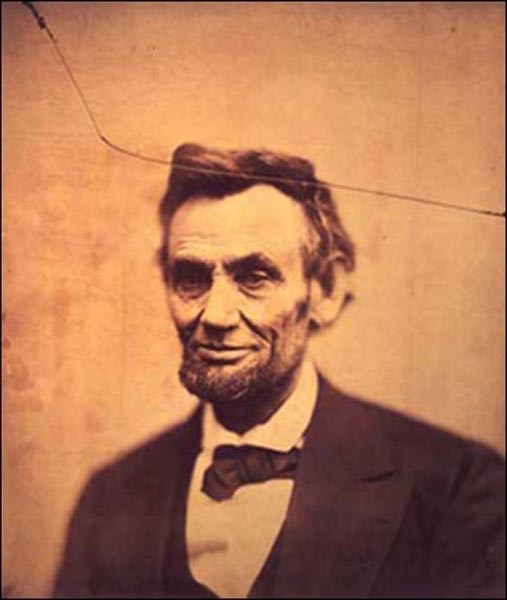

Photo 4: Abraham Lincoln.

Questions for Photos 3 & 4

1. Compare the two portraits of President Lincoln. Can you tell which picture is taken at the beginning of his presidency and which picture is taken at the end? What clues support your answer?

2. How does President Lincoln’s face look different in the two photographs? Can you infer anything about his duties as president during the Civil War?

3. Referring back to Reading 2, think about Walt Whitman’s observations about President Lincoln and look at your answers to the Walt Whitman reading questions. Do any of those same words apply to these photographs? How would you describe the president in each photo?

4. Look at photographs of a modern president from the beginning and end of his presidency. Compare these modern photographs with the Lincoln images. Has the face of the modern president changed as much as Lincoln’s did? What does this tell you about the job of a president?

Putting It All Together

The following activities will help students connect what they have learned about Abraham Lincoln, the Soldiers’ Home, emancipation, and the importance that retreats can play in people’s lives.

Activity 1: Journal Entry

Historians depend primarily on written records. Much of what we now know about President Lincoln's journey to the cottage at the Soldiers' Home is based upon first-hand accounts. Ask your students to keep a journal for two weeks of what they see, experience, and feel on their way to and from school. Tell them to include cars, people, houses, trees, etc. and whether they sang songs, sat in traffic jams, etc. Emphasize that they should both record repeated sights and experiences and also try to record something new each day. They also may draw pictures as part of the record.

After two weeks, have students review their journal and write a summary about what they saw and felt. Did they feel differently each day when they got to school or returned home based on things they had observed or experienced during their trips? Why or why not? Ask if any students would like to share their conclusions with the class. Hold a general class discussion about what remained similar or formed a pattern during that two weeks and what, if anything, changed. What do students think might change on that route over the course of the next 100 years?

Activity 2: Retreats in your Local Community

Perhaps no American president endured more than Abraham Lincoln during his Civil War era presidency. During this time the cottage truly was a retreat for the Lincoln family. Although the cottage was just three miles north of the White House, the rural setting was much more relaxing. Presidents are not the only people who need beautiful places to relax and get away from the pressures of their work. What places in your own community provide peace and quiet for everybody? Are there parks and nature preserves nearby? Buildings where people go for rest, relaxation, and a change from the demands of day-to-day life?

Have any of these places in your community been used historically as a retreat? Talk with adults and research an area retreat.

Students should draw the surroundings of the retreat and the route they would take to get there. Then have the students write a report in which they describe the retreat and answer the following questions. What does the word “retreat” mean to them? How did that influence their selection? Who has used this retreat in the past? How is it used today? What do you see along the way to this place? Would you use it as a retreat today? Find our who owns the retreat and how it is maintained. If upkeep relies on volunteer help, have students sign up to volunteer.

Divide students into groups and ask them to come up with a list of qualities that characterize a retreat. Once they have done this, if they were able to find a retreat in their community, have them compare that retreat with their list. Hold a class discussion about whether the local retreat has the characteristics they listed. Ask students, in groups, to design a retreat for their own community, which might be a building or a site. Students should select a suitable location and create a design for their retreat. Have the class vote on the design they like best and that they believe best incorporates the qualities important to them. Ask students if they would like to submit the design to their local government representative for consideration with arguments for the benefits it would bring to the community.

Activity 3: Emancipation Proclamation and Reparations

Abraham Lincoln struggled with the decision to issue the Emancipation Proclamation. Even in its realized form, it was a monumental statement for the future of America, but complex social, political, and racial issues of the 1860s and the prolonged war restrained the document. From today’s perspective it is very easy to see the limitations of the Emancipation Proclamation. Since the Civil War, the issue of reparations (compensation given to the descendants of slaves for the centuries their relatives spent in bondage) has come up again and again. Various forms of reparations have been suggested, from monetary compensation to community improvement projects to free healthcare and education. At the end of the Civil War, General William Tecumseh Sherman issued Special Field Order no. 15, which has come to be known as the “40 acres and a mule” plan.

Basically, Sherman’s plan set aside land in parts of Georgia and South Carolina to help the formerly enslaved build a better future. However, after Lincoln’s death, President Johnson struck down Sherman’s orders. Many proponents of reparations point to the termination of this program as proof of the government’s failure to take responsibility for slavery, and the debate over reparations continues today.

Have students research the reparations debate of 1865. Using what they have learned through their research and referring back to the Emancipation Proclamation, ask the students to add an amendment to the Emancipation Proclamation. The amendment should answer the question of what will become of the freed slaves. Would they give reparations to those formerly enslaved? If so, what is their plan? Would the freed slaves stay in the south? Would they move to the north or west? Would students give the freed slaves land, money, livestock, and/or supplies? Where would they get the land and/or money for this? If they displaced southern whites, what would students do with those they displaced? Or would students not intervene and leave those formerly enslaved to work out their own economic situation? Finally, how might students use this newly created section of the Emancipation Proclamation to build an integrated society based on equal opportunity? Encourage your students to be creative. Students should write out their reasoning.

Activity 4: Current Issues

The debate over slavery challenged the United States since its beginning. For decades prior to the Civil War, the debate raged. Many wanted to expand slavery west into the new territories while others called for the end of slavery. Even those advocating the abolition of slavery couldn’t agree. Some thought freed blacks should enter American society; others promoted re-colonization to Africa. After two devastating years of civil war, President Lincoln felt he had to take decisive action against slavery.

Today, there also are issues that spark heated debates within communities, states, and the nation. Ask students to research a current event in which there is an obvious dispute over the best resolution. The issue can be national, state, or local. Students should research both sides of the issue. They should list the main points of contention, the major arguments, and the resolutions offered by each side. They should also state how the issue originated and give a little background as to whether it is new or ongoing. After outlining the different positions, ask students to formulate and write out their own solution to the issue, as if they held elected office. How would they resolve this issue? Would they take one side over the other? Would they come to a middle ground? Or would they do something unique, coming to a totally different conclusion? What factors influenced their decision? Did they have a difficult time making a decision? Stage a debate between two or more students holding different opinions.

President Lincoln's Cottage: A Retreat--

Supplementary Resources

President Lincoln’s Cottage: A Retreat teaches students about President Abraham Lincoln’s public and private activities during the Civil War, focusing especially on the importance of his family’s retreat at the Soldiers’ Home in Washington, DC Those interested in learning more will find that the Internet offers a variety of interesting materials.

President Lincoln’s Cottage at the Soldiers’ Home

Visit the website for President Lincoln’s Cottage at the Soldiers’ Home for more information about the history of the cottage and the Lincoln presidency, as well as current efforts to preserve and restore the building for the public. They have a great blog that is constantly updated with useful Lincoln websites and news.

Library of Congress

The Library of Congress’ American Memory website includes Abraham Lincoln’s papers, Civil War photographs, sheet music about President Lincoln, Emancipation, and the Civil War, and more.

National Archives--The Emancipation Proclamation and The Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation

President Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863, and the Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation on September 22, 1862.

The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History

The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History offers thousands of documents related to the political and social history of the United States.

Washington, DC: The American Experience

Washington, DC: The American Experience offers information about visiting Washington, DC and contains numerous maps of the city and surrounding area. Most of the maps are interactive and easy to browse.

New Jersey Division of Parks and Forestry: The Walt Whitman House

Visit the Walt Whitman House website to discover more information about Walt Whitman. This site offers historical background information on Whitman, teaching resources, and links for students. The site also contains a link to more of Whitman’s poetry.

For Further Reading

There are two books that focus specifically on Lincoln’s time at the Cottage: Lincoln’s Sanctuary: Abraham Lincoln and the Soldiers’ Home by Matthew Pinsker (2003) and Lincoln’s Other White House: The Untold Story of the Man and His Presidency by and Elizabeth Smith Brownstein (2005).

Tags

- presidential history

- president abraham lincoln

- white house

- soldiers homes

- soldiers

- civil war

- washington dc

- dc history

- national register of historic places

- nrhp listing

- teaching with historic places

- twhp

- african american history

- emancipation proclamation

- slavery

- american presidents

- civics

- civil war history

- twhplp

- cwr aah