© Specimen from the collections of the Natural History Museum, London

Bees and flower flies are two important groups of pollinators in Denali. Without their help in carrying pollen between flowering plants, there would be no wildflowers on the tundra, no blueberries for grizzlies to eat, and no fireweed blazing along the park road. Researchers already knew pollinators are vital to Denali ecosystems, but until recently, the park knew little about the individual species that make up this invaluable group of animals.

NPS Photo / J. Rykken

Exploration of the Denali Microwilderness

During the summer of 2012, researchers collected more than 552 bees and 328 flower flies in the park. That included 20 different species of bees and 42 species of flies. In subarctic landscapes like Denali, the majority of bees you see are big fuzzy bumble bees. The reason why might seem obvious, they are wearing thick furry coats! But bumble bees have several other important adaptations for living in cold, inhospitable environments:

- They are able to shiver to raise their body temperature so they can fly in cool temperatures

- Queen bumble bees incubate their eggs to keep them warm (like birds)

- Bumble bees eat a large variety of flowers over the summer so they don’t run out of food

- Only the newly mated queens have to survive the winter, which they do by hibernating underground. The rest of the colony dies off in the fall.

Not surprisingly, of the 20 bee species collected in 2012, 13 were bumble bees. Or was it 14 species?

Photo by The President and Fellows of Harvard College

New Bumble Bee Species

A recent (2016) paper published in the Journal of Natural History by Paul Williams and colleagues describes a brand new species of bumble bee. Thus far it has only been found in two places on Earth-- Denali National Park and in the Yukon, Canada. This is big news, because bumble bees are one of the best-known native bee groups in North America. Before this discovery, it had been almost 90 years since the last new bumble bee species was discovered on this continent.

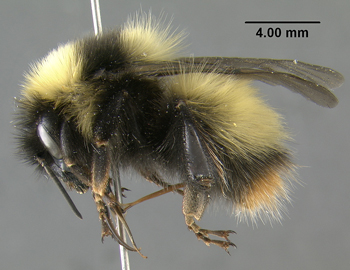

This new bumble bee, named Bombus kluanensis, resembles a bee commonly known as the “active bumble bee” (Bombus neoboreus). Both bees are members of the subgroup Alpinobombus. As the name suggests, Alpinobombus species are found in arctic and alpine places all around the northern hemisphere (e.g., Greenland, Siberia, and Norway). In Denali, there are three other species in this subgroup. One species is a “social parasite” (Bombus hyperboreus—aka the high arctic bumble bee). This bee invades the nests of other bumble bees, kills the queen, and forces the workers to raise her young! Since Alpinobombus species live in harsh conditions, all tend to have bigger bodies and extra-long fur. So how did scientists know that they had found a new species if it looked so much like the other arctic bees?

The first evidence indicating that Bombus kluanensis was a new species came from examining its DNA. Routine sequencing of bee genes determined that two bees collected in the Yukon were different enough genetically from Bombus neoboreus that they likely represented a new species. That prompted researchers to check for more bees with matching gene sequences. Sure enough, three more bees (all from Denali) were found among the many examined. On closer examination, there were also some subtle anatomical differences between B. kluanensis and B. neoboreus. These anatomical differences could be used to tell them apart (without extracting DNA), including the length of the “cheek” and the color patterns of fur on the thorax and abdomen. Using these characteristics, researchers can look out for more specimens of this species in future surveys of Denali pollinators.

Photo by The President and Fellows of Harvard College

New Flower Fly Species

Bombus kluanensis isn't the only new kid on the block. Another new pollinator researchers would like to find more individuals of is a flower fly in the genus Cheilosia. A single unique individual was found in 2012, near the East Fork River in Denali. No other specimens like this one have been found anywhere in the world. Chris Thompson, a retired entomologist from the Smithsonian Institution, discovered the new Cheilosia species among samples sent to him from the 2012 survey. In this case, he could tell they were a different species entirely from external anatomy.

There are about 11 other species of Cheilosia already known from Alaska and more than 80 found in North America. They are generally small, black, shiny flies, unlike most flower flies that are black and yellow mimics of wasps and bees. Flower fly adults feed on nectar and pollen much like bees. But, unlike bee larvae that develop in a nest and have pollen and nectar supplied to them, flower fly larvae must go out and find their own food. In the case of Cheilosia larvae, this means feeding on fungi or plant stems, roots, or leaves.

Pollinator inventory work continues in Denali. Over the coming years, researchers hope to find more surprises in the micro-wilderness as they work to get a better understanding of the full diversity of these amazing and irreplaceable insects.

Last updated: December 19, 2016