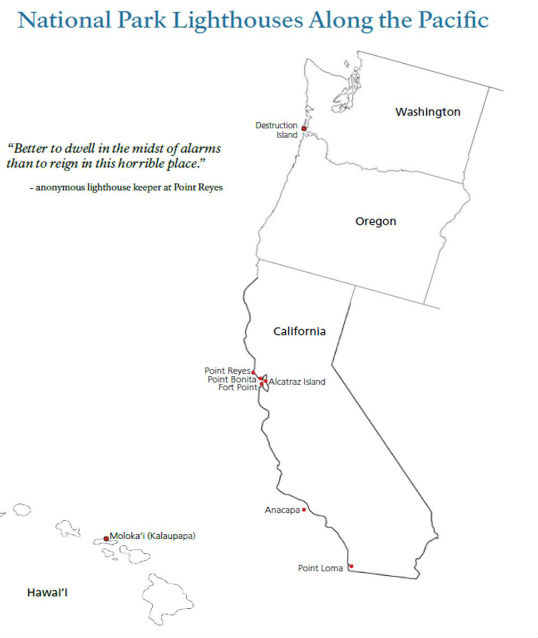

"Better to dwell in the midst of alarms than to reign in this horrible place." Anonymous lighthouse keeper at Point Reyes

A Beacon of Light for the Channel Islands

© Tim Hauf

The thick fog and strong currents of the Santa Barbara Channel have proved treacherous to maritime traders and other vessels for centuries. Sea captains traveling to San Francisco along the west coast of Central and South America avoided the narrow passage for much of the nineteenth century, for fear of colliding with one of the islands in darkness, fog or stormy conditions. Since its completion in 1932, the Anacapa Island Lighthouse has helped guide sailors through the precarious Channel waters. Still, the fractured remains of shipwrecks are chilling reminders of nature’s enormous power.

An estimated nine-tenths of all vessels trading up and down the Pacific Coast were passing through the Santa Barbara Channel by 1920. Members of the American Association of Masters, Mates and Pilots demanded a fog signal as well as a light. A permanent lighthouse, however, required authorization by Congress. When the tank steamer Liebre grounded on the east end of Anacapa Island on February 28, 1921, directly under the light tower, local inspectors blamed the inadequate station.

In 1928, the Bureau of Lighthouses allotted funds for fog signal and radio apparatus for Anacapa, as well as boats and miscellaneous improvements for water supply, sanitation, and grounds improvement. The new lighthouse’s keeper, Frederick Cobb, lit the first light on March 25, 1932. In 1939 the U.S. Coast Guard replaced the Lighthouse Service.

Atop the Cliffs of Anacapa

Located on the highest point of East Anacapa Island, the Anacapa Island Lighthouse became an indispensable resource to shipping and passenger boats. At the top of the 39-foot concrete cylindrical tower flashed a third-order Fresnel lens, one of the most advanced lighthouse beacons in the world. From 1931 through the 1960s, the light station housed a crew of between 15 and 25 people who maintained the lens, fog signal and tower, hourly weather and radar monitoring and reports, and a radio tower. When the US Coast Guard automated the station in the 1960s, the need for a fully manned station ended and the light station was able to be operated from the mainland.

For 57 years the light station aided ships traveling through the Santa Barbara Channel. In 1989, the Coast Guard replaced the historic Fresnel lens with a solar-powered acrylic lens. These modern lenses are small versions of Augustin Fresnel’s invention, using the same technology employed by the nineteenth-century physicist. In 1961 the Coast Guard modernized the light station by replacing the fog signal system and installing electrical appliances. The following year, however, a new plan was outlined to automate the Anacapa Island Light Station and to establish a rescue facility at Point Hueneme Light Station.

By 1970 the National Park Service and the U.S. Coast Guard reached an agreement that awarded joint custody and use of the unimproved land areas of East Anacapa, the wharf, hoist house, and hoist. NPS park rangers now occupy the residence quarters and operate the other buildings. While the park service manages the island, the Coast Guard operates the lighthouse and fog signal building.

For safety reasons, visitors to Anacapa Island are not permitted to tour the lighthouse, but the Park Service welcomes you to explore the area surrounding this historic structure and to experience the unparalleled views from Anacapa’s rocky shores.

Illuminating the Past

The Old Point Loma Lighthouse stood watch over the entrance to San Diego Bay for 36 years. At dusk on November 15, 1855, the light keeper climbed the winding stairs and lit the light for the first time. What seemed to be a good location 422 feet above sea level, however, had a serious flaw. Fog and low clouds often obscured the light. On March 23, 1891, the light was extinguished and the keeper moved to a new lighthouse location closer to the water at the tip of the Point. Today, the Old Point Loma Lighthouse still stands watch over San Diego, sentinel to a vanished past. The National Park Service has refurbished the interior to its historic 1880s appearance - a reminder of a bygone era. Ranger-led talks, displays, and brochures are available to explain the lighthouse’s interesting past.

© Tim Hauf (left), NPS (right)

A Challenging Place

© Bruce Farnsworth

Point Reyes is the windiest place on the Pacific Coast and the second foggiest place on the North American continent. Weeks of fog, especially during the summer months, frequently reduce visibility to hundreds of feet. The Point Reyes Headlands, which juts 10 miles out to sea, posed a threat to each ship entering or leaving San Francisco Bay. The historic Point Reyes Lighthouse, built in 1870, warned mariners of danger for more than a hundred years.

After the gold rush, Point Reyes became San Francisco’s chief supplier of dairy products and hogs, carried by schooners which sailed from Tomales Bay and Drakes Estero to the city. As early as 1849, it was recognized that Point Reyes would play an important role in the protection of coastal traffic and in the economic prosperity of the western United States. However, land disputes and political intrigue delayed the establishment of a lighthouse for another twenty years.

At a total cost of around $100,000 for the building and equipment, well over the initial $16,000 allocated for it, the Point Reyes Lighthouse began operation on December 1, 1870. The historic light remained in operation until it was decommissioned in 1975. Its navigational function has been replaced by an automated beacon located in a separate building below the lighthouse. The original lighthouse, including its remarkable lens and clockworks, is now preserved as an historic landmark.

Isolation within Isolation

© Melissa Simon

Just before sunset on September 9, 1909 a solitary light more than 200 feet off the ground beaconed to the rough seas surrounding Kalaupapa Peninsula on Moloka’i Island in the Territory of Hawai’i for the first time. Those who ran the lighthouse formed a small community at the tip of the rugged and windswept peninsula. Isolation is not unique for light stations and their keepers, but in this case there were hundreds of people (Hansen’s disease patients) living only 1.5 miles away, but contact with them was prohibited. Keepers and their families needed special permission every time they left or arrived at the station.

Patients who themselves had been isolated (often forcefully) could see the light keepers were the ones who actually felt alone and longed for companionship, so they would sneak over to talk to them.

Dean Love, 1991 Lighthouses of Hawai’i. Moloka’i. University of Hawai’i Press: Honolulu. Pgs: 97-207

Destruction Island Lighthouse

NPS

The Destruction Island Lighthouse was a warning beacon for ships passing along the Olympic Peninsula’s notorious “ship wreck coast.” For thousands of years, the island was known by its Quileute name, T’achisqu. As a canoe landing base, T’achisqu served as a meeting point during times of ocean harvests. Seals, whales, bass, halibut, salmon and shellfish, as well as “sea parrot” eggs provided important resources for coastal tribes. Later, English Captain Charles Vancouver named the island Destruction during his exploration of the coast from 1792-94.

In 1866, President Andrew Jackson used an executive order to set aside the thirty-three acre island for government use and the island was reserved under the coastal sentinel system. Over the next twenty years, Congress appropriated eighty-five thousand dollars to build the Destruction Island Lighthouse and associated buildings.

By 1889, construction problems were evident: the cisterns did not hold water, the basement was poorly laid and rain washed paint off the buildings. Laborers made repairs, but there was no budget for the tower or fog signal. So when the first keepers, Christian Zauner and his assistant arrived in 1889, there was little for them to do.

Congress appropriated an additional ten thousand dollars in 1890 for building the tower and completing the iron work. By the end of 1891, a first-order Fresnel lens was installed in the lantern room and a new steam powered fog siren began blasting every minute for five seconds. On January 1, 1892, the keeper lit five concentric wicks in the lantern room and the revolving light began flashing every ten seconds.

A principle keeper and three assistants lived on the island with their families to maintain the lighthouse and signal. The tiny community had a school for young children. Chickens, cows, rabbits and a vegetable garden supplemented rations and other supplies delivered to the island.

The Coast Guard attempted to abandon the lighthouse in 1963, but local mariner protests kept the light burning. Then an automated, low maintenance light was put into the lens in 1965. A modern light replaced the lens in 1995. The intricate Fresnel lens is now displayed at the United States Coast Guard Westport Maritime Museum in Westport, Washington. With the introduction of modern navigation and GPS, the Coast Guard turned the Destruction Island light off in April 2008.

Destruction Island is closed to the public. The island and its resources are co-managed by Olympic National Park and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s Quillayute Needles Wildlife Refuge. The waters surrounding Destruction Island are protected by NOAA’s Olympic Coast National Marine Sanctuary. Rafts of sea otters congregate in the kelp beds surrounding the island. The island is also home to the southern-most breeding colony of the burrowing rhinoceros auklet or the “sea parrot” whose eggs were prized by coastal tribes.

© U.S. Coast Guard

Contributors

John Dell’Osso, Point Reyes National Seashore

Ann Huston, Channel Islands National Park

Judy Lively, Olympic National Park

Dean Love, excerpts from his book, Lighthouses of Hawai’i

Yvonne Menard, Channel Islands National Park

Editor:

John Dell’Osso, Point Reyes National Seashore

Part of a series of articles titled Pacific Ocean Education Team (POET) Newsletters.

Previous: POET Newsletter May 2013

Next: POET Newsletter May 2014

Tags

- alcatraz island

- cabrillo national monument

- channel islands national park

- fort point national historic site

- golden gate national recreation area

- kalaupapa national historical park

- olympic national park

- point reyes national seashore

- lighthouse

- pacific ocean

- pacific ocean education team

- channel islands

- hawaii

- molokai

- ocean

- oceans

- lighthouses

- channel islands national park

- anacapa island lighthouse

- anacapa island

- east anacapa island

- santa barbara channel

- u.s. coast guard

- coast guard

- uscg

- old point loma lighthouse

- cabrillo

- cabrillo national monument

- point reyes

- point reyes national seashore

- point reyes lighthouse

- kalaupapa lighthouse

- kalaupapa national historical park

- destruction island lighthouse

- olympic national park

- olympic

Last updated: October 8, 2021