Library of Congress

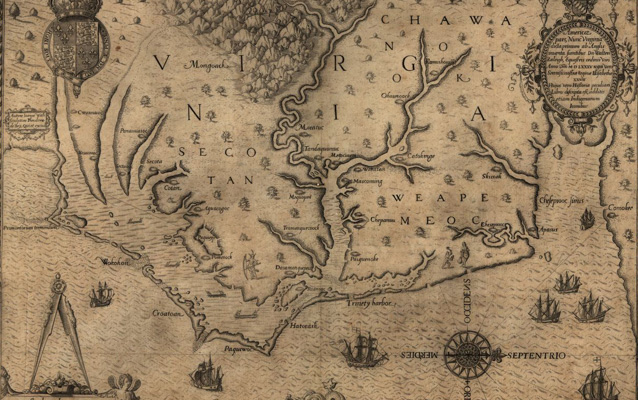

While the fate of the "lost colony", the 117 men, women, and children who vanished from Roanoke Island in 1587, focuses the majority of our attention, most of the backers of and participants in the Roanoke colonies were preoccupied with seizing wealth from the Spanish, the French, even from their own countrymen. If the Roanoke colony had not already been planned as a base for attacks on Spanish shipping in the western Atlantic, the colonists, the mariners who carried them, and the investors who underwrote the enterprise would have had few misgivings about using it as such anyway.

Piracy, the act of seizing a ship or its cargo from its lawful owners or their agents, has been endemic to maritime nations ever since man first set sail upon the high seas. By the time Queen Elizabeth I had ascended the throne in 1558, English piracy had entered into a Golden Age, as freebooters roamed its coastal waters virtually unchallenged. With fat prizes, particularly Spanish treasure ships to be found further out to sea, the plundering spread into the waters of the Atlantic and finally to the Caribbean, the well-spring of Spain's ever increasing wealth. But as the violent, frequently profitable enterprise of piracy escalated into a state of near anarchy, English commerce began to suffer heavy losses in the waters closer to home.

Library of Congress

While he received many offices and lucrative endowments from Queen Elizabeth I, one of Sir Walter Raleigh's main sources of income came from privateering enterprises. When in 1584 Raleigh acquired the patent authorizing him to search out and take possession of, for himself and for his heirs, "remote, heathen and barbarous lands" not held by any Christian prince, he sent the first reconnaissance voyage to Roanoke in the hopes that a colonial privateering scheme would add to his purse.

Since immediate returns on colonization ventures could be extremely speculative, Raleigh encouraged investors by combining colonial plans with privateering enterprises. Roanoke, with its lush vegetation, virgin forests and bountiful harvests from the sea, was indeed "Raleigh's Eden." But it was also ideally suited as a base from which the English could prey upon Spanish treasure ships as they lumbered their way north from the Caribbean to catch the homeward flowing currents of the Gulf Stream just off the coast of the Outer Banks. After leaving Ralph Lane's 1585 military colony on Roanoke, Sir Richard Grenville captured a fortune in Spanish booty on the return trip to England, which no doubt pleased the investors. That same year, the English Crown officially sanctioned the harrassment and disruption of Spanish shipping. However, when this first attempt at colonization ended in disarray in June of 1586 (not surprisingly, Sir Francis Drake rescued Lane and his men after he had returned from plundering Spanish shipping), it became more difficult for Raleigh to secure further financial backing. The tenacious and ambitious Raleigh did not waiver in his determination to gain a permanent foothold in North America and in 1587, another attempt at colonization on Roanoke was made. This time, families were to be settled on their own land in a self-governing community. But once again, privateering was to be a large part of the lucrative bait for investors.

Library of Congress

In the final analysis, interest in privateering came into direct conflict with the business of "settling" and no doubt contributed to the eventual failure of the colony. In 1588, having returned to England for supplies, Governor John White secured two pinnaces and attempted to relieve the colonists he left on Roanoke the previous summer. The captain and crew, bent on privateering enroute, received a taste of their own medicine — during an attempt to take a prize, the two pinnaces were badly damaged and were forced to turn back to England before making Roanoke. The following year yielded a bumper crop of prizes along the Spanish Main and Sir Walter Raleigh continued to reap his share of the spoils. His interest in the Roanoke colony had waned, but not his appetite for lucrative privateering ventures. When John White finally returned to Roanoke in 1590 with another privateering squadron, the colonists had vanished.

Last updated: August 18, 2017