Last updated: August 29, 2020

Article

Pipestone Indian Reservation

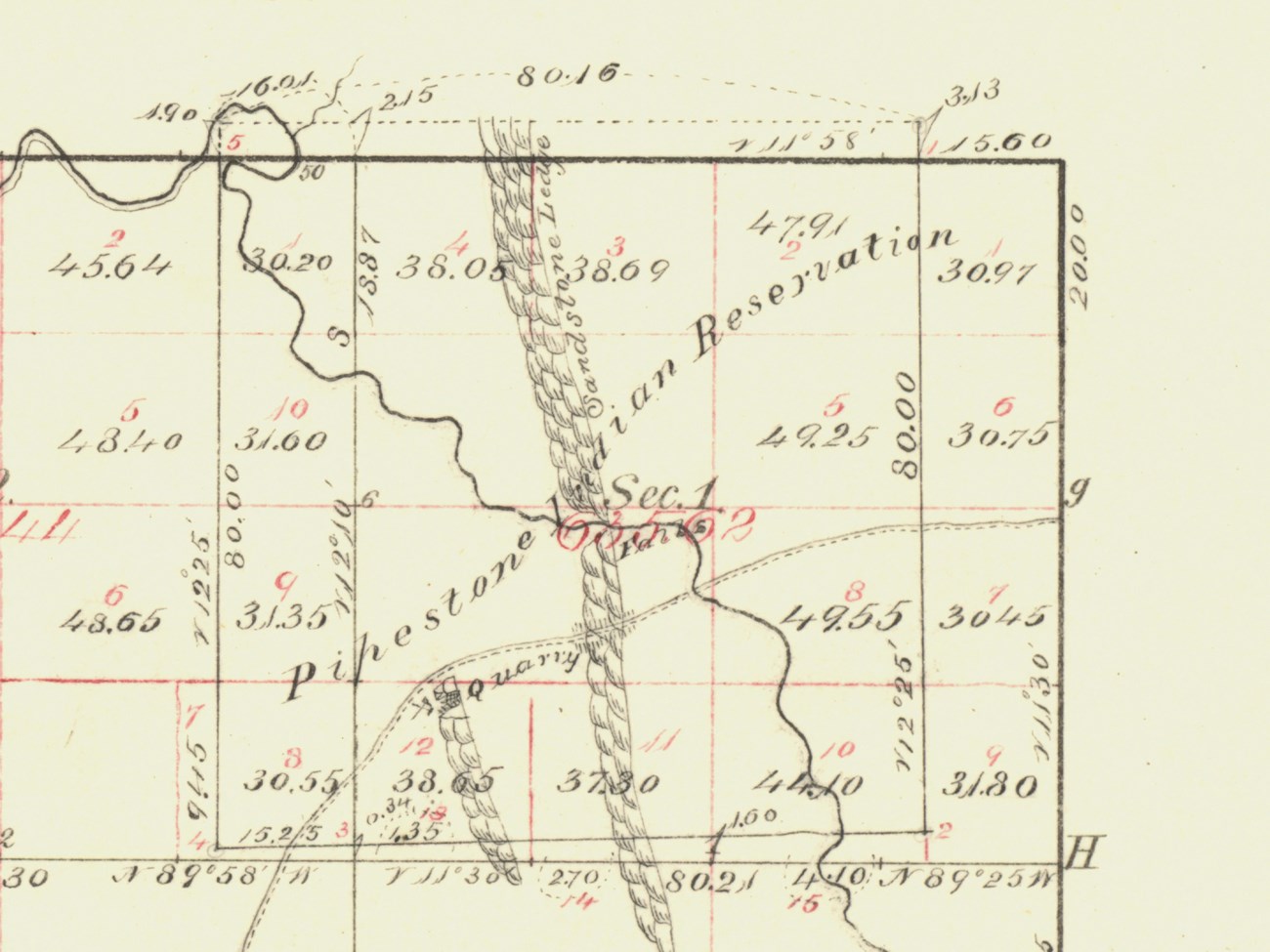

Bureau of Land Management's Government Land Office.

The Pipestone Indian Reservation was a 1 square mile (640 acre) plot of land that was set aside by the United States Government in the Treaty of 1858 with the Yankton Sioux Tribe (known as the Ihanktowan Oyate, a western Dakota group). The purpose of this reservation was not to be a place for the resettlement of the Ihanktowan Oyate, but rather to protect the tribe’s interests in quarrying for pipestone, which they used to carve pipes and other culturally significant objects. The tradition of quarrying at the pipestone quarries reaches back thousands of years by many of the American Indian groups historically affiliated with the location. Today, these quarries are protected on the former reservation’s land, at Pipestone National Monument.

The Pipestone Indian Reservation has faded into obscurity in the eyes of the United States Government, replaced by the current institutions that stand on it today. However, the subtle glimpses of its existence are still visible. The property has had a conflicted and storied past. Below, a brief overview of the land is included, but is not meant to be all encompassing.

The Creation of the Pipestone Indian Reservation

In the mid 1850s negotiations were opened with the Ihanktowan Oyate to cede land to the United States Government in the area that would become the State of Minnesota. A Ihanktowan Chief named Struck By The Ree negotiated as a representative of the Ihanktowan Oyate, and would only cede the territory if the Ihanktowan’s ability to quarry at the pipestone quarries was protected. The United States Government agreed to the protection of the land, and with this concession Chief Struck By The Ree agreed to sign the Treaty of 1858:

ARTICLE VIII. The said Yancton Indians shall be secured in the free and unrestricted use of the Red Pipe-stone Quarry, or so much thereof as they have been accustomed to frequent and use for the purpose of procuring stone for pipes; and the United States hereby stipulate and agree to cause to be surveyed and marked so much thereof as shall be necessary and proper for that purpose, and retain the same and keep it open and free to the Indians to visit and procure stone for pipes so long as they shall desire.

Today, the Yankton Sioux Treaty Monument stands at the Missouri National Recreational River to commemorate the Treaty of 1858.

After the Treaty was ratified by Congress on February 16, 1859, and signed by President James Buchanan, the Department of the Interior ordered a plat of the area by the Bureau of Land Management, setting aside 1 square mile of land to protect the quarries from homesteading and trespassing. The 640 acres of land was to be centered around the Nicollet Marker, an inscription on the cliffs next to the pipestone quarries left by the Nicollet Expedition in 1838. The surveyed piece of land was designated the Pipestone Indian Reservation and placed under the jurisdiction of the Bureau of Indian Affairs.

As the United States grew, a large populace moved West under various homesteading laws. Euro-American settlers tested the bounds and limits not only of the lands, but also the authority and enforcement of the United States Government. The Pipestone Indian Reservation was not immune to these growing pains.

Despite instructions to the Bureau of Land Management to not allow settlement, when Minnesota became a state and opened to homesteading, several homesteading permits were issued within the bounds of the Pipestone Indian Reservation. Most of these homesteading permits were caught and cancelled; however, one was approved under suspicious means. This incorrectly issued land patent was discovered years later, and the issue was subject to a Supreme Court case in 1884. The homesteader’s case argued that the Reservation only protected the quarrying rights of the Ihanktowan, and that these rights were not infringed. Ultimately, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that the land within the Reservation was not open to homesteading, as the land was set aside from settlement and should not have been issued in the first place (United States v. Carpenter, 111 U.S. 347).

Trespassing and squatting on the Pipestone Indian Reservation was rampant in the early years, and became a consistent concern of the Ihanktowan. One such claim jumper, C.C. Goodnow, built a house and fenced in area on the land, and built another house nearby for his mother on the Reservation in 1883. After the initial house was built by C.C. Goodnow, several other illegal homesteads were developed on the land.

The squatters were peacefully removed by a military detachment from Fort Randall under the orders of the Department of the Interior in 1887. When the military attachment arrived to resurvey the land and enforce the reservation boundaries by evicting the squatters, the engineers discovered that the Burlington, Cedar Rapids, and Northern Railway had laid a line through the Reservation!

This added to the conflict and tensions between all the involved parties. To settle the issue of the railroad laying track through the Reservation, the U.S. Congress passed a bill in 1889 for the Ihanktowan Oyate to receive compensation for the land used by the Burlington, Cedar Rapids, and Northern Railway. This bill also included provisions for certain tracts of lands within the Reservation to be appraised, and upon agreement by the Ihanktowan, to be sold. Another provision within that bill stated that the squatters who were evicted from the Reservation by the military were to have a chance to acquire the land they had illegally occupied if the lands were opened up for sale. The Ihanktowan Oyate declined for the lands to be sold to the squatters.

The Pipestone Indian School Reservation

In 1891 the United States Congress passed “An act for the construction and completion of suitable school buildings for Indian industrial schools in Wisconsin and other States”, signed into law by President Benjamin Harrison. The goal of this law was to create Indian Schools in the states of Michigan, Wisconsin, and Minnesota. The law explicitly selected the reservation at Pipestone, Minnesota, as the location for the government-funded Indian industrial school. The northeast section of the Pipestone Indian Reservation was selected as the ideal location for the school. The Pipestone Indian School was based off of the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Carlisle, PA. The goal of these schools was to assimilate American Indian youth into a modern United States society, by training them for futures in industry and farming. These schools effectively destroyed many aspects of American Indian culture by removing youth from their homes, families, cultures, and communities. Native languages and names were suppressed, enforced by punishments. Across the country, various American Indian boarding schools were operated by governments or religious groups and were devastating to American Indian culture.

With the land for the school being selected on the Pipestone Indian Reservation, the property became alternately known as the Pipestone Indian School Reservation, and these names have been used somewhat interchangeably at times.

The Ihanktowan contested the decision of the Federal government to use the Pipestone Indian Reservation as the location of the Pipestone Indian School. They believed that the United States Government had seized the land from the tribe and sought reparations. For years the Ihanktowan pushed the issue by fighting for justice and eventually sued. The case followed a difficult path, but was taken up by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1926. The U.S. Supreme Court ruled that Federal actions amounted to an illegal seizure and that the Ihanktowan Oyate were due compensation for the land. With the court settlement established and the Ihanktowan paid reparations, the Pipestone Indian Reservation came under full control of the U.S. Government.

The Pipestone Indian School continued its operations and grew from a small campus occupying two buildings to a large complex of 63 buildings including a hospital and staff housing. After the Pipestone Indian School was created, American Indian groups were allowed to quarry with the permission of the School’s Superintendent.

The Creation of Pipestone National Monument

The land surrounding the pipestone quarries was always an attractive site, and from the early years of the city of Pipestone, Minnesota, many residents fell in love with the land. Long before the creation of Pipestone National Monument in 1937, local citizens and businesses supported efforts to create a park at the quarries. The citizens were persistent, signing many petitions and lobbying various government agencies about the importance of the pipestone quarries and surrounding areas. At one point, the State of Minnesota had a law in place to designate the area as a State Park, but only if the land could be acquired by the state. At that time, the property was still contested and subject to then-ongoing legal battles. In 1926, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that the U.S. Government had seized the land, and that the Ihanktowan Oyate were to be paid for the whole property’s value. With the Pipestone Indian Reservation’s title cleared and in full control of the United States Government, the gates were open for the creation of a park.

In 1937 Pipestone National Monument was created through an Act of Congress, and was signed into law by Franklin Delano Roosevelt. The Monument was created to protect the pipestone quarries, but also to preserve the tradition of quarrying on the property. The original monument consisted of approximately 115 acres, which had been carved out of the Pipestone Indian School Reservation. In 1956, the acreage was increased to 301 acres, taking again from the Reservation’s acreage. The law passed in 1956 also had provisions within it to acquire small portions of land from the “Pipestone Indian School Reservation”.

The End of the Pipestone Indian Reservation

In 1953, nearly 100 years after the creation of the Pipestone Indian Reservation, the Pipestone Indian School was closed. With the closure of the School, the Bureau of Indian Affairs transferred approximately 114 acres in the northwest corner of the Reservation to the State of Minnesota Department of Natural Resources and the United States Fish and Wildlife Service as the Pipestone Wildlife Management Area. In 2019 the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources transferred the property to the full custody of the United States Fish and Wildlife Service, and it became a wildlife refuge. The Pipestone Indian School grounds west of Hiawatha Avenue were sold to the State of Minnesota Board of Education, and now serve as a campus for the Minnesota West Community & Technical College. The Pipestone Indian School Superintendent’s House is still standing on a portion of the land next to the school, and is on the National Park Service’s National Register of Historic Places. The building, as well as the small plot it stands on, is currently owned by Pipestone National Monument’s cooperating association, the Pipestone Indian Shrine Association. The land east of Hiawatha Avenue was mostly sold to the City of Pipestone, and the eastern boundary of the Pipestone Indian Reservation is still visible along those parcels’ property lines.

Today, Pipestone National Monument stands on the former lands of the Pipestone Indian Reservation, and seeks to preserve to the Pipestone Indian Reservation’s legacy.

Tags

- pipestone national monument

- american indian heritage

- american indian sites

- american indian history and culture

- pipestone

- history

- quarry

- quarry history

- stories

- boarding school

- pipestone indian school

- james buchanan

- struck by the ree

- yankton

- yankton sioux reservation

- carlisle indian industrial school

- midwest

- american indian culture

- american indian history

- native american culture

- native american heritage