Last updated: December 12, 2019

Article

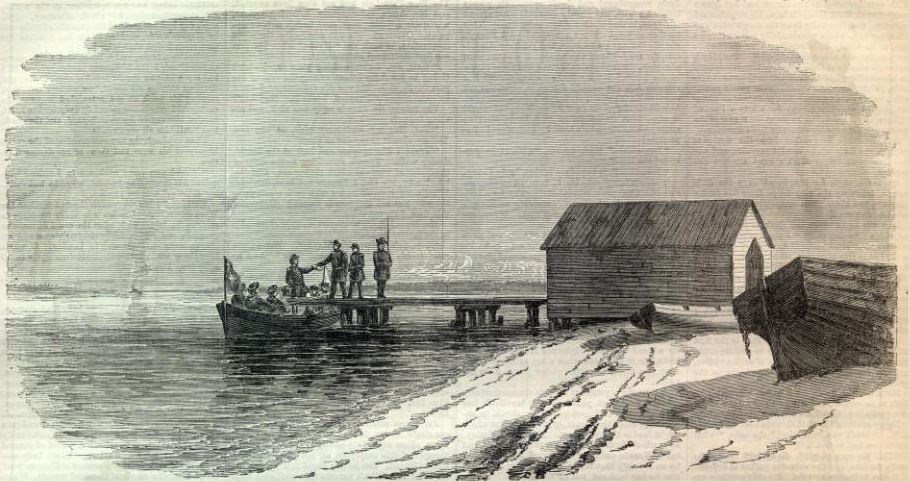

The Fort Pickens Parley

Harpers Weekly April 13, 1861.

"not worth one drop of blood"

A high-stakes meeting took place outside Fort Pickens three months before the start of the Civil War. Four men—William H. Chase, Ebenezer Farrand, Jeremiah H. Gilman, and Adam J. Slemmer—met to negotiate for the fort. The meeting's outcome would decide who controlled the most powerful fort on Pensacola Bay and one of the most important ports in the United States.

The January 15, 1861 meeting took place at a troubling time for the US. A growing sectional crisis between northern free states and southern slaveholding states threatened to tear the nation apart. Chase, Farrand, Gilman, and Slemmer illustrated the nation's divisions on a personal level.

Each man was a northerner by birth. Each had taken an oath to support and defend the US Constitution as military officers. Colonel Chase, with 42 years of service as an Army engineer, had supervised the building of Pensacola Bay's fortifications before the war. When Florida seceded from the Union, Chase followed. Commander Farrand had served in the Navy for about 38 years and also sided with the South.

2nd Lieutenant Gilman had four years of Army service before the meeting took place. Gilman remained loyal to the Union and served as Slemmer's top officer and closest adviser. 1st Lieutenant Slemmer, meanwhile, had served in the Army for 10 years. Like Gilman, Slemmer remained loyal to the Union. As the senior army officer present for duty, it fell onto Slemmer to defend the bay.

Pensacola Bay was the site of four masonry forts, 376 cannon, 17,452 projectiles, and 52,254 pounds of gun powder. A navy yard capable of building, repairing, modifying, and supporting ships sat within the forts' protection. Beyond the forts and the navy yard was the bay, the deepest anchorage on the US Gulf Coast.

To lose the bay could be seen as evidence that the Union was crumbling. To take it could strengthen Southern resolve. Though militarily more important than South Carolina's Charleston Harbor, Pensacola was not the commercial and political center Charleston was. When the black clouds of war rolled over the nation, most people looked to South Carolina.

Slemmer's orders from Washington were clear: work with the Navy to prevent the loss of the forts. But the assignment was impossible. Slemmer took 82 men to Fort Pickens by January 10, the same day Florida seceded. Two days later, Alabama and Florida militia seized the navy yard and forts McRee, Barrancas, and Advanced Redoubt. On January 15, Chase, in command of Florida's militia, set his eyes on Fort Pickens.

Chase and Farrand crossed the bay to meet Slemmer and Gilman. "I have full powers from the governor of Florida to take possession of the forts and navy-yard . . ." Chase's terms stated. "I desire to perform this duty without the effusion of blood." Chased wished to parole Slemmer and his men. Under pressure, Slemmer asked for extra time to consider the offer. Chase agreed.

Chase received Slemmer's response the next day. "We have decided . . . that it is our duty to hold our position until such a force is brought against us as to render it impossible to defend it," Slemmer wrote, "or the political condition of the country is such as to induce us to surrender the public property in our keeping. . ."

Whoever attacked the fort, Slemmer made clear, would be responsible for the bloodshed. Yet Southern leaders also avoided attacking. "The possession of the fort is not worth one drop of blood to us," they believed.

The matter was soon out of Chase and Slemmer's hands. On January 28, Stephen R. Mallory, one of Florida's former senators in Congress, sent President James Buchanan a message. As long as reinforcements stayed away, the militia would not attack the fort. This truce ensured Fort Pickens would become Abraham Lincoln's problem when he became president.

The truce broke down after March 4, the day Lincoln became president. Shortly after, Confederate General Braxton Bragg replaced Chase. Slemmer, who still occupied Fort Pickens, and Bragg struggled to maintain peace. Confederate President Jefferson Davis gave Bragg the option to attack if it led to victory. Bragg knew that victory was almost impossible, so he waited.

In his new role as commander in chief, Lincoln saw it as his duty to preserve the Union. Lincoln ordered reinforcements to land at Fort Pickens on April 1. They did not do so until the night of April 12, the same day as the first shot of the Civil War in Charleston, South Carolina.

The United States was at a crossroads when the Chase-Slemmer meeting took place. The meeting underscored the growing crisis, sweeping Americans toward war. Slemmer, Gilman, Chase, and Farrand prevented open warfare, but only temporarily. Events soon proved more potent than their feeble attempts to save human lives.

Bearss, Edwin C. “Civil War Operations in and around Pensacola.” The Florida Historical Quarterly, vol. 36, no. 2 (October 1957): 125-165.

Cullum, George W. Biographical Register of the Officers and Graduates of the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, N.Y., From its Establishment, in 1802, to 1890, with the Early History of the United States Military Academy. New York: Houghton, Mifflin and Company, 1891. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=coo.31924092703937&view=1up&seq=1.

Dibble, Ernest F. William H. Chase of Pensacola: Gulf Coast Fort Builder. Wilmington, DE: Gulf Coast Collection, 1978.

Ellis, William A. Norwich University. Her History, Her Graduates, Her Roll of Honor. Concord, NH: The Rumford Press, 1898. https://books.google.com/books?id=UJgaAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA147&lpg=PA147&dq=ebenezer+farrand&source=bl&ots=T4TJUosxyU&sig=ACfU3U0QifiwqBHW7a5qB8A8Qq9-iNRjig&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwjBmMux_4njAhUNWs0KHYgWB3Y4ChDoATAHegQICBAB#v=onepage&q&f=false.

Gambone, Albert M. The Life of Adam Jacoby Slemmer: One Strong Voice of Defiance. Baltimore: Butternut & Blue.

Gilman, Jeremiah H. "With Slemmer in Pensacola Harbor." Battles and Leaders of the Civil War: being for the most part contributions by Union and Confederate officers. New York: The Century Company, 1884. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=coo1.ark:/13960/t7dr3f63p&view=1up&seq=11.

Haskin, William L. The History of the First Regiment of Artillery, From its Organization in 1821, to January 1st, 1876. Portland, ME: B. Thurston and Company, 1879. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=chi.16542922&view=1up&seq=5.

Pearce, George F. Pensacola During the Civil War: A Thorn in the Side of the Confederacy. Miami: University Press of Florida, 2000.

U.S. Government. The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, ser. 1, vol. 1. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1880. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=coo.31924077725913&view=1up&seq=3.

Walby, David L. William Henry Chase: Uniquely American. Denver: Outskirts Press, 2014.