Last updated: November 29, 2021

Article

The Philippine War - A Conflict of Conscience for African Americans

Phillipine War

Following the Treaty of Paris, which ended the Spanish American War in December of 1898, the United States took control of the former Spanish colonies of Puerto Rico, Guam, and the Philippines.

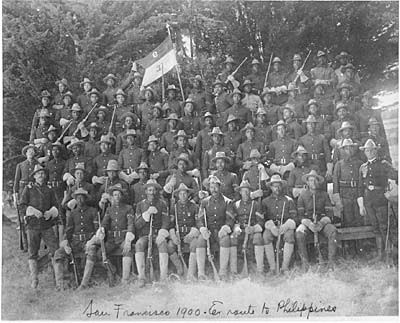

Companies from the segregated Black infantry regiments reported to the Presidio of San Francisco on their way to the Philippines in early 1899. In February of that year Filipino nationalists (Insurectos) led by Emilio Aguinaldo resisted the idea of American domination and began attacking U.S. troops, including the 24th and 25th Infantry regiments.

The 9th and 10th Cavalry were sent to the Philippines as reinforcements, bringing all four Black regiments plus African American national guardsmen into the war against the Insurectos.

Within the Black community in the United States there was considerable opposition to intervention in the Philippines. Many Black newspaper articles and leaders supported the idea of Filipino independence and felt that it was wrong for the United States to subjugate non-whites in the development of what was perceived to be the beginnings of a colonial empire. Bishop Henry M. Turner characterized the venture in the Philippines as "an unholy war of conquest." (21)

But many African Americans felt a good military showing by Black troops in the Philippines would reflect favorably and enhance their cause in the United States.

![“Ida B. Wells-Barnett, wearing ‘Martyred Negro Soldiers’ button, ca. 1917-1919, 23.8 x 19 cm.” Source: Wells, Ida B. Papers(link is external), [Box 0010, Folder 12], Special Collections Research Center, University of Chicago Library. “Ida B. Wells-Barnett, wearing ‘Martyred Negro Soldiers’ button, ca. 1917-1919, 23.8 x 19 cm.” Source: Wells, Ida B. Papers(link is external), [Box 0010, Folder 12], Special Collections Research Center, University of Chicago Library.](/articles/images/ida_b_wells_1600x1200.jpg?maxwidth=650&autorotate=false)

“Ida B. Wells-Barnett, wearing ‘Martyred Negro Soldiers’ button, ca. 1917-1919, 23.8 x 19 cm.” Source: Wells, Ida B. Papers(link is external), [Box 0010, Folder 12], Special Collections Research Center, University of Chicago Library.

Editorials Against Fighting

"Ida Wells-Bartlett Against Expansion"

Ida Wells-Barnett spoke on "Mob violence and Anarchy, North and South." She said Negroes should oppose expansion until the government was able to protect the Negro at home. -- Cleveland Gazette, January 7, 1899, from an account of a meeting of the Afro-American Council, Washington D.C.

"Colonization Against the Declaration of Independence"

Particularly at this while she [the U.S.] is busy on a hair-brained attempt to go into the colonizing business against its own Declaration of Independence and while she is making such frantic clamor of some kind of independence which she has up her sleeve for Cuba and the Filipinos, would it be extremely wise for the American Negro to show up to the entire civilized world the class of liberty they enjoy here...

-- Washington Bee, June 24, 1899

"End the War in the Philippines"

The colored American is for "expansion," but he wants expansion on lines consistent with the human principles, for the establishment of which he has given his labor and shed his blood in four wars....

-- Colored American (Washington, D.C.), December 2, 1899

Editorials For Fighting

"Black Troops Should Go to the Philippines"

It is now said that colored troops are to be sent to the Philippines. The sooner the better. The Negroes must be taught that the enemy of the country is a common enemy and that the color of the face has nothing to do with it. -- Indianapolis Freeman, July 1, 1899

"The Philippine War is No Race War"

It pays to be a little thoughtful.... The strife [against the Philippines] is no race war. It is quite time for the Negroes to quit claiming kindred with every black face from Hannibal down. Hannibal was no Negro, nor was Aguinaldo [the Filipino nationalist leader]. We are to share in the glories or defeats of our country's wars, that is patriotism pure and simple. -- Indianapolis Freeman, October 7, 1899

Source: George P. Marks, III, The Black Press Views American Imperialism (1898-1900), Arno Press and the New York Times, New York, 1971

The service of the cavalry in the Philippines was described as daily and nightly patrols by small detachments commanded by junior officers or sergeants. Troops often encountered insurgent bands armed with captured Spanish and American guns and bolos. (22)

As the war progressed many African American soldiers increasingly felt they were being used in an unjust racial war. The Filipino insurgents subjected Black soldiers to psychological warfare, using propaganda encouraging them to desert. Posters and leaflets addressed to "The Colored American Soldier" described the lynching and discrimination against Blacks in the United States and discouraged them from being the instrument of their white masters' ambitions to oppress another "people of color." Blacks who deserted to the Filipino nationalist cause would be welcomed and given positions of responsibility. (23)

During the war in the Philippines, fifteen U.S. soldiers, six of them Black, would defect to Aquinaldo. One of the Black deserters, Private David Fagen became notorious as a "Insurecto Captain," and was apparently so successful fighting American soldiers that a price of $600 was placed on his head. The bounty was collected by a Filipino defector who brought in Fagen's decomposed head.

A Black newspaper, the Indianapolis Freeman, editorialized in December, 1901, "Fagen was a traitor and died a traitor's death, but he was a man no doubt prompted by honest motives to help a weakened side, and one he felt allied by bonds that bind. (24)

The sentiments of most Black soldiers in the Philippines would be summed up by Commissary Sergeant Middleton W. Saddler of the 25th Infantry, who wrote, "We are now arrayed to meet a common foe, men of our own hue and color. Whether it is right to reduce these people to submission is not a question for soldiers to decide. Our oaths of allegiance know neither race, color, nor nation." (25)

Credit: U.S. Army Military History Institute

Wars End

Resistance finally collapsed with the capture of independence leader Aguinaldo and the eventual wearing down of the indigenous fighters by the better armed and trained American soldiers.

The African American regiments would be honored for their service in the Philippines, and several senior noncommissioned officers, such as Medal of Honor recipient Edward L. Baker, would become officers in the newly established Philippine Scouts. (26)

One Black infantryman described his duty with resignation, "We're only regulars and black ones at that, and I expect that when the Philippine question is settled they'll detail us to garrison the islands. Most of us will find our graves there." (27)

Following the war, Buffalo Soldier regiments continued to serve at a series of army posts in the United States, Hawaii, and the Philippines. It was in the following early years of the 20th century that these troops played a prominent role on the West Coast at the Presidio of San Francisco, Yosemite National Park, and Sequoia National Park.

Article Footnotes #21 - 27