Last updated: November 14, 2019

Article

Peter, Property, and Posterity

Florida Memory

There are many unanswered questions about the enslaved African American men who built Pensacola’s masonry fortifications. What were their names? What did they look like? Did they have wives or children? What about their fears? What were their dreams? We may never know the answers to all these questions, but one person provides a glimpse of who these people were: Peter Dyson.

Peter was possibly born in Kentucky to an enslaved couple. At some point in time he showed up in the Pensacola region. Whether Peter moved from Kentucky with his master or was separated from his family and sold to a new slave owner in Florida is a mystery.

The slave economy grew in Pensacola between 1820–1830, around the same time Peter was born. The US military rented slaves for many projects on the bay. The practice of paying slave owners to rent enslaved people was common in the South, and proved quite profitable. In Pensacola, the Navy used enslaved men to build a new navy yard to construct and fix ships. The Army depended on enslaved workers too. Enslaved men built Fort Pickens, Fort McRee, Fort Barrancas, Barrancas Barracks, and part of Advanced Redoubt.

Three of Pensacola's defenses were completed by 1851 when Peter was rented as a mason. His work likely included laying missing or damaged bricks and repointing mortar joints. Peter received a cash incentive of $3.50 a day, which was customary for rented slaves. These incentives were commonly divided with owners who used them to control the enslaved population. A few years later, Peter was sent to work in the navy yard.

With the start of the Civil War in April 1861, enslaved men, women, and children in the South hoped that the moment for their liberation was near. Union armies immediately became magnets for enslaved refugees. The Union army at Fort Pickens was no exception. Peter likely believed if he and his wife Henrietta could escape to the fort that they would be given protection and freedom.

Peter planned an escape in the first summer of the war. He was determined to run away with Henrietta after overhearing his owner threaten to use slaves to fight for the Confederacy. “The slaves were to be put in front of the rebel batteries with arms in their hands, and forced to fight,” Peter told a reporter. “In case they refused,” explained Peter, “they were to be shot down by the rebels themselves.”

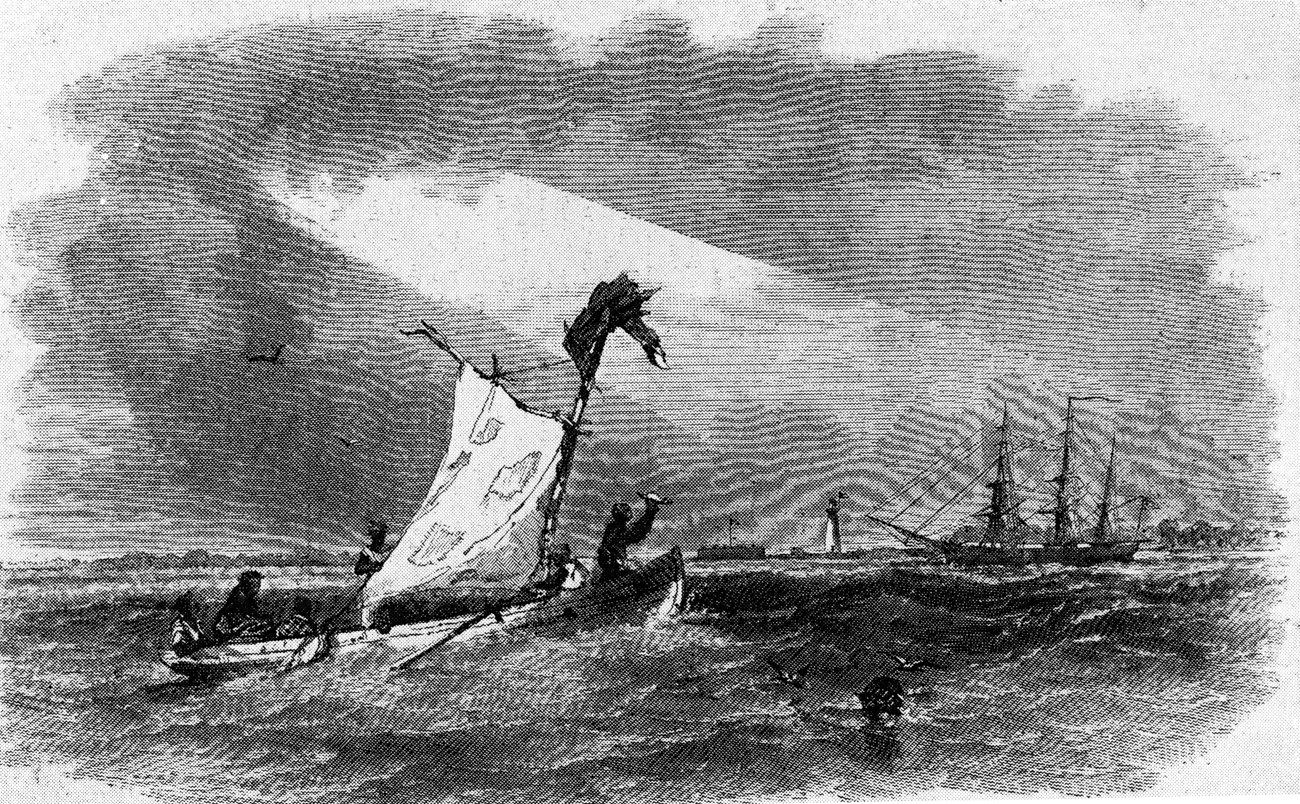

The first escape attempt failed because of Confederates patrolling Pensacola Bay. Undaunted, the couple devised a second escape, which succeeded. The pair slipped by the Confederate patrols in a skiff and crossed the bay. Peter and Henrietta remained with the Union army until October when they sailed northward, bound for freedom.

Peter and Henrietta reached New York City in October 1861. They likely settled in or near the bustling city where Peter could find work. Though they resided in a free state, they were still legally enslaved. They lived in the shadow of a nation struggling over the legality and morality of slavery and the future of human equality and civil rights. Peter continued living in New York until his death in 1888.

The Emancipation Proclamation of 1863, followed by the 13th Amendment in 1865, eventually broke the shackles that bound nearly 4 million African Americans to slavery. Through his escape, Peter fought the injustice and barbarism of his enslavement. While the Civil War was an event that decided the fates of the United States and of slavery, people like Peter knew it was something so much more. To him and many others, it was an instrument of progress.

Peter Dyson’s plight transcends time and place. Today his legacy endures in the masonry forts that still stand on Pensacola Bay and in every person who advocates for human equality and decency. His stands as a testament to the nameless, faceless, and forgotten people who still suffer under the yokes of hate and intolerance. His story serves as a rallying cry for us to learn about the forgotten champions of human rights.