Last updated: December 23, 2019

Article

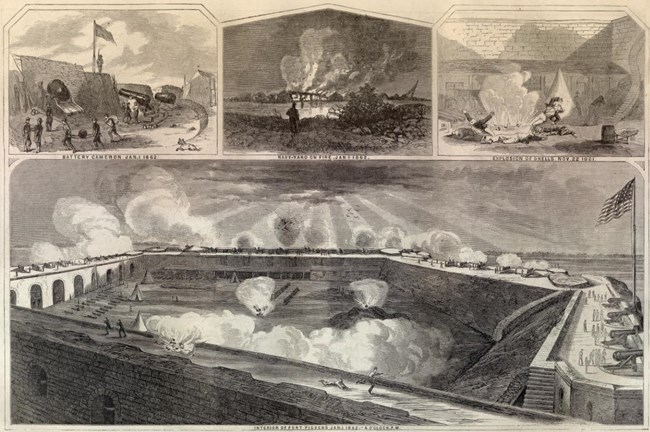

The Second Bombardment of Pensacola Bay

Harper's Weekly

“a perfect hell of confusion & strife”

Civil war engulfed the United States by January 1862. East and west of the Appalachian Mountains, Union and Confederate forces dotted the landscape, ready to march and fight. In northwest Florida, Union and Confederate soldiers welcomed the New Year engaged in a fierce bombardment that warned of hardships and sacrifices for both the North and the South.

Little had changed on Pensacola Bay since the battles fought in October and November 1861. The Union army, under the command of Colonel Harvey Brown, firmly held the western end of Santa Rosa Island. Their defenses included Fort Pickens and four sand batteries made of sandbags and lumber, named batteries Lincoln, Cameron, Scott, and Totten. The arrival of the 75th New York Volunteer Infantry Regiment in December 1861, and the continued support of the 6th New York Volunteer Infantry Regiment, cemented Brown’s hold of the barrier island.

Major General Braxton Bragg’s Confederate army stood defiantly to the north and west of Fort Pickens. Bragg’s army possessed a strong defensive line that stretched for about four miles, with the Pensacola Navy Yard on the mainland to the east and Fort McRee on Perdido Key to the west. Situated between were numerous defenses, including Fort Barrancas, the Spanish Water Battery, and more than a dozen sand batteries. Confederate and Union soldiers, sailors, and marines went about their day-to-day duties, their cannon aimed at one another, waiting to be provoked.

On the afternoon of January 1, a steamer bound for the navy yard came within cannon range of Fort Pickens. Colonel Brown ordered his artillerymen to fire several shots at the ship, which prompted a sporadic response from the Confederates. The exchange awakened the fury of both armies, and soon a bombardment ensued.

Fighting continued all day and late into the night. “The scene during the night,” wrote a Northern reporter, “was magnificent in the extreme . . . every shell could be traced in its course through the air from the time it left the gun until it exploded”. John N. Chamberlin, a soldier from New York, described the power of the cannon in a letter to his mother. “The calm of Nature seemed turned into a perfect hell of confusion & strife," Chamberlin wrote.

Alexander C. Jones, a Confederate officer from Mississippi, tried to do more than paint the scene for his sister. He tried to express how he felt in his first battle. “I do not know how I felt,” he admitted. “I know it was not fear or anything like it that came over me. Every one seemed to be like myself actuated by some superhuman desire to take part in the engagement . . . I do wish I could convey an idea of the scene & the feelings that inspire men on such occasions.” His efforts, Jones finally conceded, were useless. “I am ashamed of my attempt at a description . . . for my description falls so short of the reality . . .”

The fight ended in the predawn hours of January 2. Bragg, who was absent during the battle, lamented the loss of a “large and valuable store-house, with considerable property, in the navy-yard . . .” To his relief, Bragg reported no men killed, wounded, or missing. Brown reported two men injured, but neither severely, and that his defenses suffered no severe damage. Most of the damage, it seemed, was in the villages of Woolsey and Warrington, which bordered the navy yard.

For many Americans, the New Year’s holiday was a day to reflect upon the past while looking forward to the future. It was a day when neighbors, friends, and families gathered to celebrate a shared tradition and strengthen the bonds of community. On January 1, 1862, however, Americans were incensed over current events, and division replaced feelings of community. This bombardment indicated that the struggle over the Union and the institution of slavery would be full of more pain and deeper division.