Do humpback whales vocalize differently in “loud” environments than they do in

quiet ones?

Project Dates

August 2012 - December 2013

Did You Know?

Humpback whales can produce sounds underwater continuously for 15 minutes or more, during which time no air escapes from either the blowhole or mouth. Whales apparently produce sounds by circulating air through their lungs, mouth, and a huge, expandable larynx that serves as a resonating chamber.

Introduction

Graduate student Kerri Seger is investigating how all the different sources of physical, biological, and anthropogenic sound in an area combine to create an underwater soundscape, and how soundscapes affect the calls made by humpback whales. This information is of interest to resource managers because whales use calls in Glacier Bay to assist in vital life functions such as facilitating feeding groups and protecting their calves. Sound is how whales engage with the world around them.

This study will investigate temporal patterns in humpback whale acoustical activity as it relates to human activity. By recording underwater sounds at four different locations, the researchers seek answers to several questions: How can the ambient noise environments of the locations be characterized, and how do they compare with each other and change over time? What are the relative contributions of noise by large ships and small vessels? Are the sound levels and frequency bands sufficient to impede communication between individuals by drowning out (or “masking”) their own acoustic signals?

Finally, differences in humpback whale sounds will be examined for correlation with levels of human activity, to help in understanding whether whales change the structure of their calls to accommodate for human noise sources.

Methods

Expanding upon long-term acoustic monitoring begun by the NPS and U.S. Navy in 2000 at the entrance to Bartlett Cove, the researchers deployed underwater microphones (hydrophones) in four new locations with differing restrictions on (and levels of) human activity.

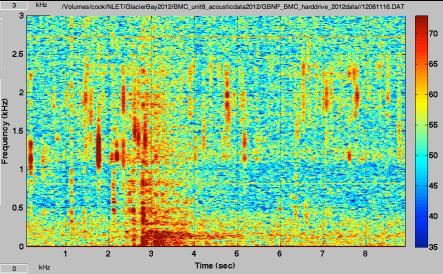

Two autonomous passive-acoustic hydrophones were deployed outside Blue Mouse Cove (a regulated but well-traveled area) and in Hugh Miller Inlet/Scidmore Bay (a designated Wilderness area where motorized vessels are prohibited) during the humpback whale feeding season in August-September 2012 and again in May-October 2013. The sites were selected to compare the underwater "noise budgets" of a relatively heavily-used portion of the park with a relatively isolated portion. In 2013, two hydrophones were also placed in unregulated waters outside the park in Icy Strait so that a broader span of human activity levels could be explored. The hydrophones are tethered to the seafloor and kept at an average depth of 70 meters by subsurface buoys until the researchers call them back to the surface.

It will be important to characterize the variability in whale calls among individuals in order to understand whether changes in humpback whale call types can be correlated with different sound levels in the environment.

Findings

The researchers are still analyzing the 2012 data, but have made some general observations. Three types of sounds were recorded: biological, human, and physical (weather-related). At least three different humpback whale sounds (“grunt,” “grumble,” and “whup”) were recorded at both sites. Seal mating calls and knocking sounds believed to be produced by fish were commonplace. “Seal bombs” (small—and illegal—explosives used to scare seals away from fishing equipment) were detected at both sites. At 2:00 pm every day the tour boat was a dominant noise source in Blue Mouse Cove; some of the sound seemed to spread into the Wilderness site, too. Physically, a storm on August 28-29 created the highest overall sound levels for the entire audio record at both sites.

Learn More

Glacier Bay National Park website. www.nps.gov/glba/naturescience/acoustics.htm

Last updated: September 28, 2016