Last updated: February 15, 2026

Article

Canyoneering at Grand Canyon National Park: Monitoring pockets of wilderness in the canyon corridor

By Matt Jenkins

Visitors to Grand Canyon National Park (Grand Canyon) associate the area with breathtaking vistas and the 277-mile (446 km) stretch of the Colorado River that flows within the boundaries of the park. However, tucked deep below the canyon’s north and south rims is an extensive network of rugged gorges and slot canyons replete with vast natural beauty and cultural resources and the potential for a lifetime of adventure for intrepid explorers. In particular, four spectacular side canyons, Garden Creek, Pipe Creek, Phantom Creek, and Ribbon Falls, are mostly “hidden” in plain view of three of the most popular hiking trails in the National Park System (see map). These pockets of scenic wilderness require technical canyoneering skills to reach, and have remained relatively untouched until recently (fig. 1). In this article I outline the growth of canyoneering at Grand Canyon and current management frameworks used to study the related impacts. I also present a case study that characterizes challenges related to visitor experience and resource protection.

NPS/Matt Jenkins

The rise of canyoneering at Grand Canyon

Outdoor activities with elements of risk and challenge have been growing in popularity nationwide, and they are anticipated to continue to expand (Access Fund 2008; Cordell 2012; White et al. 2014). This growth can be attributed to a variety of factors, including newer, safer, and more easily available equipment; an increase in college and university outdoor programs that offer adventure recreation curricula; new instructional texts and videos; the growth of commercial guide and instructional programs; and the widespread availability of information on recreation areas through guidebooks and the Internet (Access Fund 2008). This rise in adventure recreation is mirrored by the increasing popularity of canyoneering at Grand Canyon, which has been documented by park rangers, reported in backcountry use statistics, and evidenced by the increasing number of social media–related trip accounts posted on the Internet by park visitors.

Canyoneering is a multidisciplinary activity that emerged in the 1960s as distinct from mountaineering and rock climbing, although it has similarities to both, particularly with regard to the use of ropes and anchors to facilitate rappelling and provide protection from falls. It developed primarily in southern Utah in areas near Zion Canyon, the Escalante River, and the San Rafael Swell but has now spread to Grand Canyon where participants explore, traverse, and descend the park’s remote canyon tributaries (fig. 2).

Courtesy of Rich Rudow

In 2011 Todd Martin published Grand Canyoneering: Exploring the rugged gorges and secret slots of the Grand Canyon, the first guidebook to feature technical canyoneering routes in the park. The influential guide documents 105 canyoneering routes within park boundaries of which 68 require rappelling, 63 necessitate swimming or wading, and 78 usually take more than one day to complete. Many of the routes also require the use of pack rafts—small, lightweight, inflatable boats—to navigate the Colorado River in order to facilitate a return back to one of the canyon rims. In addition to the routes described in Grand Canyoneering, I have concluded from analysis of other publications, NPS GIS data, and informal personal communications that approximately 200 more routes could exist in the park.

These routes vary in popularity likely because of length, type, approach, difficulty, crowding, quality, scenic value, distance from urban population centers, area ethics, regulations, and need for specialized gear (Access Fund 2008). Studies of rock climbers, for example, revealed that the two most important factors affecting their choice of a climb are quality and difficulty of the route. Murdock (2010, p. 117) determined that “climbers are seeking a high return, or a high quality climbing experience that also matches difficulty requirements, for their hiking investment in wilderness.” In that study of climbers at Joshua Tree National Park, all selected routes ranked at least 2 on a 0−5 quality scale, and the great majority were only moderately difficult (Yosemite Decimal System 5.7–5.9).

At Grand Canyon National Park, backcountry patrols have documented increasing canyoneering activity over the past several years. The most popular routes are scenic, accessible, moderately difficult, and can be completed in a day with gear that most canyoneers already own. These routes are within a one-day drive of popular tourist hubs such as Phoenix, Flagstaff, and Las Vegas, and are located in popular backcountry use areas with large campgrounds. Thus canyoneering has become a priority for park management because of the need to balance recreational use opportunities with adequate resource and visitor experience protections.

Management context

More than 1.1 million acres (94% or 0.4 million ha) of Grand Canyon National Park qualify for wilderness designation, and are managed as “proposed wilderness” to protect the character and suitability of these lands for possible inclusion in the National Wilderness Preservation System (USDI 1995; US Wilderness Act 1964). Although none of the side canyons discussed in this article are located in designated or proposed wilderness, they are nonetheless untrammeled and undeveloped, with a primeval character that park policy protects.

This setting contrasts with much of the corridor trail system where bridges, buildings, utilities, and other improvements mark the landscape. Murdock’s (2010) conclusions about climbers’ route selection and observations by Grand Canyon backcountry rangers suggest that the side canyons associated with the corridor trail system present several canyoneering routes that entice those who have not learned low-impact ethics specific to technical canyoneering. This is important because inexperienced canyoneers may go on to alter the character of other routes located throughout the proposed wilderness of Grand Canyon (Miller et al. 2001).

Grand Canyon National Park’s 1988 Backcountry Management Plan outlines three long-range goals that apply generally to canyoneering: (1) maintain and perpetuate natural ecosystem processes, (2) protect and preserve historical and prehistoric cultural resources, and (3) provide and promote a variety of backcountry recreational opportunities that are compatible with resource protection and visitor safety (USDI 1988, p. 4). In 1995 the park’s General Management Plan added five objectives to help meet these goals for the management of undeveloped areas. First, visitor use and park resources are to be monitored and managed to protect resources, ecosystem processes, and wilderness experiences, and a primitive experience should be preserved in areas that are not proposed wilderness. Second, indicators are established so that management actions can be initiated as resource conditions fall below a certain threshold. Third, opportunities for primitive types of recreation are provided, consistent with NPS policy. Fourth, administrative activities such as search and rescue are conducted as needed. Fifth, user conflicts are minimized (USDI 1995).

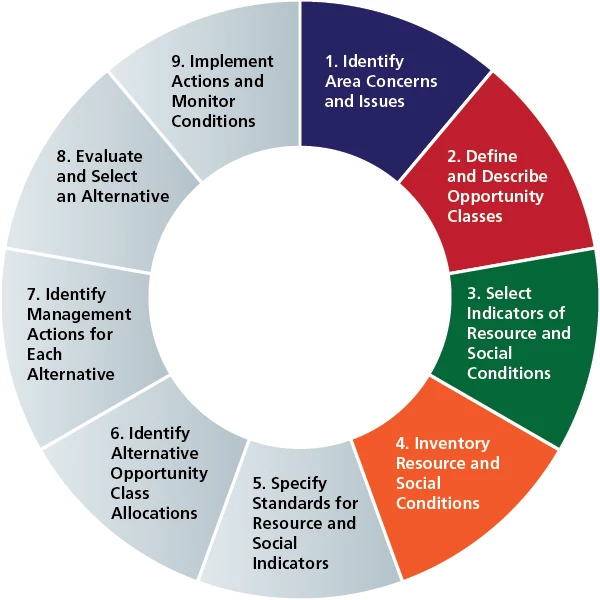

Limits of Acceptable Change (LAC)

LAC is a wilderness planning framework (fig. 3) that is suitable for management of conflicting goals and concerns about change in resources, social conditions, or management. It is fundamentally similar to the Visitor Experience and Resource Protection (VERP) framework, and both work well in situations where recreation conflicts with resource preservation, as is the case with canyoneering (Dawson and Hendee 2009; Lime and Stankey 1971; Hof and Lime 1997).

Illustration adapted from Lime and Stankey (1971) by NPS/Matt Jenkins

In 2012, park managers completed the first and third steps in the LAC process (fig. 3), identifying issues and concerns related to canyoneering, and selecting indicators of resource and social conditions. Step 2, which defines an area’s “opportunity class,” or management zone, is addressed in the backcountry and general management plans. Grand Canyon National Park has four opportunity classes: corridor, threshold, primitive, and wild. The corridor zone is characterized by structures, maintained trails, and the availability of potable water, whereas the wild zone lacks routes and reliable water sources. The threshold and primitive zones are the middle two opportunity classes and vary by the degree to which routes and water sources exist or are difficult to locate (i.e., more difficult in the primitive zone).

These opportunity classes were designed with traditional backcountry uses, such as day hiking, backpacking, and stock use, in mind and they do not translate directly to canyoneering. All of the side canyons are rugged, pristine, and inaccessible even though they may be located in any of the four opportunity class zones. Moreover, at present, regulations and permitting are the same for canyoneering routes regardless of opportunity class.

By going through the process to analyze limits of acceptable change and in consideration of management objectives, the backcountry rangers implemented a canyoneering monitoring program in 2012. This program serves as the foundation of a revised management strategy for addressing the rising popularity of canyoneering. Program staff completed an initial survey of 36 canyoneering routes from March 2012 to January 2013 and identified indicators of resource and social conditions. Since then, we have formally monitored numerous other canyoneering routes as part of LAC step 4. We gathered data on route characteristics such as use levels; social impacts on the route, approach, and exit (table 1); natural resource features such as soil, springs, and wildlife; and cultural resource conditions.

Table 1. Social impacts monitored as part of the canyoneering monitoring protocol |

||

| Impact | Detail | How Measured/Documented |

| Rope | Number of abandoned ropes, excluding hand lines, on route | |

| Hand line | Number of abandoned hand lines on route | |

| Anchor | Unnecessary | Number of unnecessary anchors on route |

| Removed | Yes/No (Monitor removes unnecessary webbing and rope) | |

| Notes | Narrative provided by monitor about abandoned technical gear encountered | |

| Social trails | A, B, or C, as follows: A = none, B = 1–5 visible social trails, C = more than 5 | |

| Cairns | A, B, or C, as follows: A = none, B = 1–5 cairns, C = more than 5 | |

| Graffiti | Yes/No | |

| Litter | Nonorganic | Yes/No (Includes tape, adhesive bandages, plastic bags, and similar items) |

| Organic | Yes/No (Includes banana peels, apple cores, and similar items) | |

| Human waste | Yes/No (Monitor notes improper disposal of human waste in canyon) | |

Through continued monitoring managers hope to answer questions of how canyoneering affects wildlife habitat (particularly bighorn sheep), how to minimize the unnecessary placement of fixed anchors, and what the best strategies are for avoiding conflicts between user groups. Although recreational climbing has been managed for many decades at many levels of government throughout the country, few precedents exist for the management of technical canyoneering and its broader implications for wilderness character. The following case study illustrates a primary concern related to canyoneering at Grand Canyon National Park.

Case study: Proliferation of fixed anchors in the corridor

In 2011 Todd Martin, author of Grand Canyoneering, described Garden Creek as “a hidden gem located in close proximity to the most popular trail in Grand Canyon National Park.” He also indicated surprise that “more people hadn’t discovered the canyon.” Still a gem, it has since been discovered.

Initially descended in the 1990s, the Garden Creek canyoneering route remained relatively dormant because of high-volume waterfalls, challenging down-climbs, and a lack of publicly available information. In approximately 2010, canyoneers installed a single rappel anchor, a bolt (fig. 4), midway down the largest waterfall. Before the addition of this bolt, at least 700 feet (213 m) of rope was needed to descend Garden Creek because of a 350- to 400-foot (107−122 m) rappel halfway through the canyon. The addition of the bolt divided the rappel into two shorter sections and diminished the amount of rope necessary for the rappel to 400 feet (122 m), a more affordable and common length of rope.

NPS/Matt Jenkins

Next, Grand Canyoneering was published in 2011. This widely distributed book describes every available rappel anchor on the 105 documented routes, including the aforementioned bolt. In a matter of months, the simple combination of a more convenient rappel point and publicity of the route made Garden Creek one of the most popular and sought-after canyoneering routes in the park.

Rappel anchors are given substantial scrutiny by resource managers compared with other social impacts of wilderness adventure sports. Some of the most popular hiking and climbing routes in the National Park System, such as the famous Cable Route hike on Half Dome and the Nose climb on El Capitan in Yosemite National Park, depend on fixed anchor placements. However, controversy revolves around them because fixed anchors remain in place, often for long periods, and are considered installations or improvements (American Safe Climbing Association 2001). This has ramifications for areas managed as wilderness or for retention of primitive recreational values because fixed anchors can either be permitted as a minimum tool or prohibited as an installation (Murdock 2010). Table 2 outlines different fixed anchor management policies in various units of the National Park System. At Grand Canyon, the guidelines in Director’s Order 41, Section 7.2, are followed with respect to fixed anchors (USDI 2013).

Table 2. Fixed anchor management strategies at various units of the National Park System |

||||||||

| Activity and Wilderness Setting | Park | |||||||

| Arches National Park | Black Canyon of the Gunnison National Park | Devils Tower National Monument | Grand Canyon National Park | Joshua Tree National Park | Rocky Mountain National Park | Yosemite National Park | Zion National Park | |

| Climbing | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Canyoneering | Yes | No | No | Yes | Limited | Limited | Limited | Yes |

| Wilderness status | Proposed | Yes | No | Proposed | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Motorized drilling | Proposed wilderness: no motorized drills. Non-wilderness: Special use permit required | No | No | No | Permit required | No | No | No |

| Bolting | Permit for new bolts; one-to-one replacement of old bolts | Permit for new bolts; one-to-one replacement of old bolts with hand drill | No new bolts. Permit required for one-to-one replacement of old bolts with a hand drill | Permit for new bolts. Authorization for the replacement or removal of existing fixed anchors. See USDI 2013. | Non-wilderness: No permit for hand drilling. Wilderness: One-to-one replacement of old bolts; permit for new bolts. |

Clean anchor ethic whenever possible | Hand drill for all new and old bolts | Hand drill for all new and old bolts |

An alternative to a fixed anchor is a small loop of removable nylon webbing slung around a natural feature (fig. 5), and this is the most common form of anchor found in Grand Canyon. Bolts, pitons, and other metal hardware are used less frequently because of the need for special equipment, the expenditure of time, and the physical effort required for their placement (Access Fund 2008). Most uses of removable nylon webbing are considered “clean” anchors, while hardware such as bolts and pitons are considered “fixed.” Table 3 shares the total number of anchors per canyoneering route in Grand Canyon, and table 4 illustrates the different types of anchors.

NPS/Debbie Brenchley

Table 3. Anchors per canyoneering route, Grand Canyon National Park |

|

| Number of Anchors | Corresponding Number of Routes |

| 0 | 31 |

| 1 | 6 |

| 2 | 18 |

| 3 | 5 |

| 4 | 14 |

| 5 | 9 |

| 6 | 5 |

| 7 | 7 |

| 8 | 6 |

| 9 | 1 |

| 10 | 1 |

| 11 | 1 |

| 12 | 0 |

| 13 | 1 |

| Note: Data are from Grand Canyoneering (Martin 2011). | |

Table 4. Clean vs. fixed anchors |

||

| Type | Number | Percentage of Total Anchors |

| Clean | ||

| Pinch point | 95 | 29% |

| Rock chock | 55 | 17% |

| Boulder | 38 | 12% |

| Tree | 36 | 11% |

| Rock bollard | 21 | 6% |

| Knot chock | 15 | 5% |

| Rock horn | 13 | 4% |

| Natural arch | 12 | 4% |

| Deadman | 0 | 0% |

| Shrub | 0 | 0% |

| Total | 285 | 88%* |

| Fixed | ||

| Bolt (single) | 23 | 7% |

| Bolt (multiple, with chain) | 15 | 5% |

| Piton (single) | 2 | 1% |

| Other | 2 | 1% |

| Total | 42 | 14%* |

| *Totals do not equal 100% because of rounding. Notes: Data are for 105 canyoneering routes described in Grand Canyoneering (Martin 2011). Most uses of removable nylon webbing are considered clean, while hardware such as bolts and pitons is considered fixed. |

||

In 2012, a second bolt was installed next to the preexisting bolt in Garden Creek (fig. 4). Then, in spring 2013, visitors reported numerous additional bolts and a follow-up monitoring trip documented 12 new bolts installed along the route. Not only had the previously installed clean anchors been replaced by bolts, but also multiple pour-offs that had not had any kind of anchor were now bolted.

My analysis of rappel anchor data throughout the park reveals one significant finding regarding bolts and other fixed hardware placements in Grand Canyon. Once an initial piece of fixed gear has been installed along a route, more fixed gear placements are likely to follow. Several canyons, including Garden Creek, exemplify this trend.

National Park Service policy recognizes canyoneering as a legitimate and appropriate use of backcountry and wilderness (USDI 2013). Fixed anchors such as those found throughout Garden Creek should be used only rarely and they should serve as a “minimum tool” when the terrain or features limit the possibility of clean anchor use. The initial bolt placed in Garden Creek arguably was not necessary since the first party to descend the canyon did not put it there, and certainly the installation of 12 additional bolts was unnecessary and a degradation of park resources.

Conclusion

According to the American Canyoneering Academy (2002, p. 13), “Part of the attraction of canyoneering is the sense of discovery and adventure [canyoneers] feel as [they] descend each canyon for the first time. This sensation is heightened when [the canyons are] in their natural state, showing minimal evidence of previous visitors.” Despite Garden Creek being located in one of the busiest backcountry areas in the National Park System, it remained relatively pristine until recently. The type and rate of impacts documented in this canyon raise concerns that are being addressed by park staff in the revision of the park’s backcountry management plan. Alternatives being considered are day-use permits, group size limits, revised fixed anchor policies, and the requirement for human waste to be packed out of narrow canyons.

Park resources, visitor experiences, and wilderness values could be jeopardized if the trends continue. Dawson and Hendee (2009, p. 490) believe that “recreational use will continue to grow; and there will be more demand for day use and easy access; more demand for information; more demand for challenge, adventure, and risk-taking activities; and, a greater diversity of users.”

Staff at Grand Canyon National Park recognizes that the bureau must balance resource preservation with visitor use and enjoyment. In addition to supporting long-term park planning such as the revision of the backcountry management plan, the canyoneering monitoring program is being used to increase educational and public outreach efforts. First, canyoneering-specific Leave No Trace information is distributed to all visitors who identify themselves as canyoneers during the backcountry permitting process. The data and photography collected by park employees while on monitoring patrols are being used to develop a canyoneering-specific addition to the park website. And the National Park Service has partnered with the Coalition of American Canyoneers, a nonprofit organization, on restoration and cleanup projects such as bolt and trash removal at Grand Canyon.

Garden Creek is an icon of the corridor trail system and may be a looking glass for long-term trends in resource conditions in the remote, wilderness side canyons of Grand Canyon National Park. It demonstrates that resource and social conditions can degrade quickly through the careless acts of one group or the cumulative effects of many well-intentioned groups. Implementation of new management strategies, including the canyoneering monitoring program, revision of the backcountry management plan, and increased education and outreach, will help ensure that the National Park Service’s mission of resource preservation and visitor enjoyment will be maintained in Grand Canyon’s tributaries, such as those in the corridor.

References

Access Fund. 2008. Climbing management: A guide to climbing issues and the development of a climbing management plan. The Access Fund, Boulder, Colorado, USA. Available at https://www.accessfund.org/uploads/ClimbingManagementGuide_AccessFund.pdf.

American Canyoneering Academy. 2002. Canyoneering. Accessed 12 August 2012 at http://www.canyoneering.net.

American Safe Climbing Association. 2001. Climbing history and the ethics of bolting. Available at http://www.safeclimbing.org/conservation_bolthist.htm.

Cordell, H. K. 2012. Outdoor recreation trends and futures: A technical document supporting the Forest Service 2010 RPA Assessment. General Technical Report SRS-150. Southern Research Station, USDA Forest Service, Asheville, North Carolina, USA. Available at http://www.srs.fs.usda.gov/pubs/40453.

Dawson, C., and J. Hendee. 2009. Wilderness management. Fulcrum Publishing, Golden, Colorado, USA.

Hof, M., and D. W. Lime. 1997. Visitor experience and resource protection framework in the National Park System: Rationale, current status, and future direction. Pages 29–36 in S. F. McCool and D. N. Cole, compilers. Workshop proceedings: Limits of acceptable change and related planning progress. General Technical Report INT-GTR-371. Rocky Mountain Research Station, USDA Forest Service, Ogden, Utah, USA. Available at http://www.treesearch.fs.fed.us/pubs/23907.

Lime, D., and G. Stankey. 1971. Carrying capacity: Maintaining outdoor recreation quality. Pages 174–184 in E. vH. Lason, editor. The Forest Recreation Symposium, State University of New York College of Forestry. USDA Forest Service, Northeastern Forest Experiment Station, Syracuse, New York, USA. Available at http://www.treesearch.fs.fed.us/pubs/14579.

Martin, T. 2011. Grand Canyoneering: Exploring the rugged and secret slots of the Grand Canyon. Todd’s Desert Hiking Guide, Phoenix, Arizona, USA.

Miller, T., W. Borrie, and J. Harding. 2001. Basic knowledge of factors that limit the practice of low-impact behaviors. Draft report INT-97068-RJVA on file at Rocky Mountain Research Station, Aldo Leopold Wilderness Research Institute, University of Montana, Missoula, Montana, USA.

Murdock, E. 2010. Perspectives on rock climbing fixed anchors through the lens of the Wilderness Act: Legal and environmental implications at Joshua Tree National Park, California. Dissertation. University of Arizona, Tempe, Arizona, USA.

United States Department of the Interior (USDI). 1988. Backcountry Management Plan, Grand Canyon National Park. National Park Service, Grand Canyon National Park, Arizona, USA.

———. 1995. General Management Plan, Grand Canyon National Park. National Park Service, Grand Canyon National Park, Arizona, USA.

———. 2013. Director’s Order 41: Wilderness stewardship. National Park Service, Washington, DC, USA. Available at https://www.nps.gov/policy/DOrders/DO_41.pdf.

US Wilderness Act of 1964. Public Law 88-577. 78 Statute 890. 3 September 1964.

White, E. M., J. M. Bowker, A. E. Askew, L. L. Langner, J. R. Arnold, and D. B. K. English. 2014. Federal outdoor recreation trends: Effects on economic opportunities. National Center for Natural Resources Economic Research, Working Paper Number One. US Forest Service, Washington, DC, USA. Available at http://www.fs.fed.us/research/docs/outdoor-recreation/ficor_2014_rec_trends

_economic_opportunities.pdf.

About the author

Matt Jenkins is a backcountry law enforcement ranger stationed at Grand Canyon National Park, Arizona. He can be reached by e-mail at e-mail us.