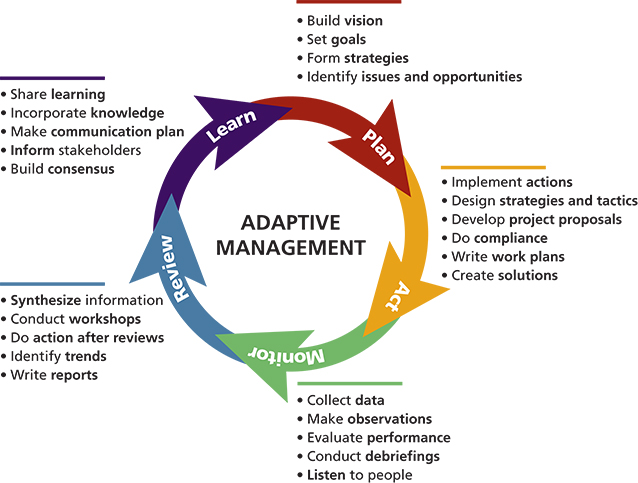

Abstract: In 2015, Rocky Mountain National Park (Colorado) celebrated 100 years of protecting high-elevation ecosystems and wilderness character while providing visitors access to inspiring wild places. We took this centennial year as a time of celebration and a time for reflection on the strengths and weaknesses of our resource stewardship program. While the mountains within the park have changed relatively little over the past century, our approach to integrating science into park and wilderness management has changed dramatically. It is only recently that we have had the capacity to embrace adaptive management (fig. 1) and work with partners to effectively use science to inform policy and management actions.

Key words: history, research, research learning centers, resource management, Rocky Mountain National Park

National Park Service

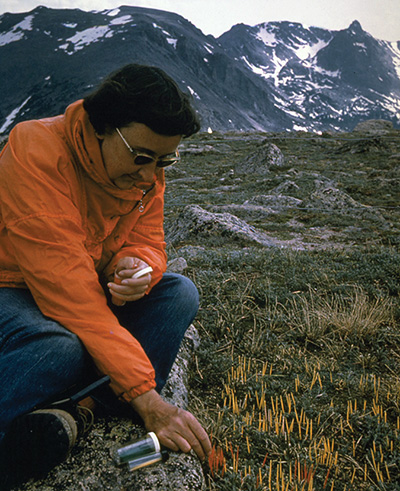

NPS Photo

IN THE FIRST 30 YEARS OF PARK HISTORY, naturalists from the park, other federal agencies, academic partners, and citizens were inspired to catalog and describe what the American public had decided to protect and preserve for future generations. For instance, in 1917 Dr. Willis Lee published “The Geological Story of Rocky Mountain National Park” and in 1933 Ruth Nelson published “Plants of Rocky Mountain National Park.” In the following decades, similar works appeared about subalpine lakes, glaciers, plants, birds, conifer distribution, and mammals. By the 1960s, research began to address specific management questions. As an example, in the 1960s and 1970s, Beatrice Willard investigated the effects of road construction and visitor trampling on alpine tundra (fig. 2), which altered the way the park manages its alpine resources and visitor use. Sporadic research by NPS staff, other agencies, and academics continued through subsequent decades, but it lacked a clear agency mandate and the administrative support required to ensure an integration of research and park management (see Hess 1993 for a more thorough discussion).

The National Parks Omnibus Management Act of 1998 (Public Law 105-391, 112 Statute 3497) and the subsequent Natural Resource Challenge initiative (NPS 1999) had a huge impact on Rocky Mountain. The Omnibus Management Act directed park units to utilize the “highest quality science and information” in decision making (Section 202). A year later, the Natural Resource Challenge provided funding for a dedicated research administrator and, in 2000, funding was provided for the creation of the Continental Divide Research Learning Center (https://www.nps.gov/rlc/continentaldivide) as part of the NPS Research Learning Center Network (https://www.nature.nps.gov/rlc).The purpose of the network is to bring “science to parks and park science to the public.” At the same time, the Cooperative Ecosystem Studies Unit (CESU) Networks were also established by the Challenge. The Rocky Mountain CESU (http://www.cfc.umt.edu/cesu) provided the park with a mechanism for partnering with and funding academics and other federal agencies on science, technical assistance, and education projects. With better administrative, logistical, and political support, many researchers were attracted to work in Rocky Mountain. On an annual basis, the park now issues an average of 120 research permits, with researchers working in the park on a diversity of topics including social science, archaeology, plant and animal species, wetlands, alpine tundra, and the spread of exotic species.

Our current challenge has not been the park’s or our partners’ capacity for research, but rather synthesizing and communicating the vast amount of science information to park management and the public. The park has worked to communicate science to a range of audiences through research briefs, lecture series, ranger programs, short videos, publications, and Web content. One of our most successful strategies to foster research and communication has been to hold two-day research conferences during which staff, students, and researchers are encouraged to share their work with the public. Recently, the park has tried a new approach to synthesizing research efforts in a Natural Resource Vital Signs Report (Franke et al. 2015). This short collection of articles provides another example of our science communication program.

In the following four articles, we provide a few vignettes of the success stories from the last 100 years of research and science in Rocky Mountain National Park. In the first vignette, Therese Johnson and colleagues explore how a foundation of science allowed the park to move forward on an elk and vegetation management plan. Next, Kathy Tonnessen shows the strong link between science and management as it relates to air quality. The author highlights the efforts across park boundaries to build collaborations with industry and regulators to reduce nitrogen deposition in Rocky Mountain. Mark Fiege then surveys environmental history at Rocky Mountain and its connections to science. His work serves to remind us that history and science are integrally linked, and that it is necessary to explore the past to understand the present condition of the park. Finally, Ben Bobowski provides the conclusion and describes opportunities for the future of science in Rocky Mountain.

Literature cited

Franke, M. A., T. L. Johnson, I. W. Ashton, and B. Bobowski. 2015. Natural resource vital signs at Rocky Mountain National Park. Natural Resource Report NPS/ROMO/NRR–2015/946. National Park Service, Fort Collins, Colorado, USA.

Hess, K. 1993. Rocky times in Rocky Mountain National Park: An unnatural history. University Press of Colorado, Boulder, Colorado, USA.

National Park Service (NPS). 1999. Natural Resource Challenge: The National Park Service’s action plan for preserving natural resources. U.S. Department of the Interior, Washington, D.C., USA. Available at https://www.nature.nps.gov/challenge/assets/actionplan.index.htm.

About the authors

Isabel Ashton was the director of the Continental Divide Research Learning Center at Rocky Mountain National Park. She is now an ecologist with the NPS Northern Great Plains Inventory and Monitoring Network. Ben Baldwin was a research learning specialist with the Continental Divide Research Learning Center. He is now the Volunteer and Youth Programs manager for the Intermountain Region. Ben Bobowski is the chief of Resource Stewardship at Rocky Mountain National Park. Scott Esser and Paul McLaughlin are ecologists with the Continental Divide Research Learning Center at Rocky Mountain National Park.

Download: PDF of this article

This article published

Online: 6 May 2016; In print: 25 March 2016

URL

https://www.nps.gov/ParkScience/articles/parkscience32_2_68-69_ashton_et_al_3840.htm

Suggested citation

Ashton, I., B. Baldwin, B. Bobowski, S. Esser, and P. McLuaghlin. 2016. Honoring the past and celebrating the present: 100 years of research at Rocky Mountain National Park. Park Science 32(2):68-69.

This page updated

5 May 2016

Site navigation

• Back to Volume 32, Number 2

• Back to Park Science home page

Last updated: February 15, 2026