Unsuspecting visitors’ lack of knowledge of Lyme disease may put them at increased risk of disease and decreased adherence to prevention practices.

Abstract: In 2013, Lyme disease was the fifth most common nationally notifiable disease and is endemic in the Northeast. Greenbelt Park, a National Park Service–administered unit, is located in a highly endemic area of Maryland near Washington, D.C. In 2010, the National Park Service and the Maryland Department of Health and Mental Hygiene implemented a park-based knowledge, attitudes, and practices survey for employees, day visitors, and campers to better understand the risk of exposure to ticks. The survey was administered to employees both before (n = 32) and one month after (n = 19) a tick-borne disease training. Day visitors (n = 127) and campers (n = 53) were invited to participate voluntarily in a parallel survey; they did not receive training, but were asked to complete their survey one month after their visit. Many aspects of employee Lyme disease transmission knowledge improved post-training. Employees with previous Lyme disease were more likely to tuck their pants into socks. However, no other protective measures were significantly changed for employees, day visitors, or campers. Reinforcement of prevention messages, including seasonal education on tick prevention methods as well as signs and symptoms of tick-borne diseases, is warranted for all groups at Greenbelt Park and other national parks where tick-borne diseases are endemic.

Key words: behavior, knowledge, Lyme disease, prevention, zoonoses

CDC/Jim Gathany

LYME DISEASE IS THE MOST COMMONLY REPORTED VECTOR-BORNE DISEASE in the United States. Maryland is one of 13 states that contributed to 96% of all Lyme disease cases reported nationally in 2011, and in 2013 Lyme disease was the fifth most common nationally notifiable disease (CDC 2015). Lyme disease is concentrated heavily in the Northeast and upper Midwest. Concern for the disease is high in Maryland, as evidenced by the presence of several Lyme disease advocacy groups, an increase in congressional funding for Lyme disease prevention activities in 2007, and ongoing state and federal legislative activities. Black-legged tick (Ixodes scapularis) nymphs and adults infected with the bacteria Borrelia burgdorferi can transmit Lyme disease to hosts if attached and feeding for at least 24 hours (fig. 1). Nymphal ticks are the primary vectors because their small size makes it difficult to see and remove them. In addition, their peak host-seeking behavior in the spring and early summer corresponds with peak human outdoor activity. Recommended tick preventive measures include (1) wearing repellents such as DEET, (2) showering within two hours after coming indoors, and (3) regularly checking the body for ticks after being outside.

NPS Photo

Greenbelt Park, a National Park Service (NPS)–administered unit in Maryland located approximately 12 miles (19 km) northeast of Washington, D.C., is an urban oasis featuring a 174-site campground, 9 miles (14 km) of trails, and three picnic areas (fig. 2). From July to November 2010, there were 179,516 total park visitors (including both day visitors and campers) to and 32 employees working at the park. The park is home to numerous deer, mice, and other mammals that support a healthy population of ticks, including I. scapularis and the lone star tick (Amblyomma americanum).

National parks as well as other natural areas present environments for zoonotic disease transmission because of close encounters with fauna that are less common in other settings (Eisen et al. 2013; Adjemian et al. 2012; Han et al. 2014). At Greenbelt Park, both employees and park visitors may have prolonged occupational exposure to wildlife, including those that may harbor zoonotic pathogens. Because Lyme disease is concentrated primarily in the Northeast and upper Midwest in nonurban areas, park visitors from other parts of the United States and other countries may not know that the park has ticks or recognize the associated risk of Lyme disease. The same is true for park visitors who live in nearby urban settings where tick populations are not abundant. Unsuspecting visitors’ lack of knowledge of Lyme disease may put them at increased risk of disease and decreased adherence to prevention practices. To better understand the potential risks of exposure to ticks, the NPS Office of Public Health and the Maryland Department of Health and Mental Hygiene (DHMH) embarked on a collaborative effort to assess the knowledge, attitudes, and practices of employees and park visitors.

Methods

In July 2010, the National Park Service and DHMH implemented a visitor survey that assessed knowledge and attitudes regarding tick-borne disease, activities in the park, proven effective prevention measures taken in the park, and history of physician-diagnosed tick-borne disease. A similar survey was administered to park employees to assess their knowledge, attitudes, and practices regarding tick-borne disease and prevention measures.

The surveys were based on a survey instrument used in a previous collaborative effort between the National Park Service and the Pennsylvania Department of Health at Gettysburg National Military Park (Han et al. 2014). Question formats were true-false, multiple choice, and free form. Paper surveys distributed at the park included a stamped envelope for return to DHMH. Online surveys were administered using Survey Monkey.

On 2 August 2010, Greenbelt Park employees voluntarily and confidentially completed surveys immediately before taking part in required tick-borne disease prevention training. This training provided an overview of ticks and tick-borne diseases of the United States, highlighted those of local concern, and described prevention methods employees could use to protect themselves. One month later, employees completed a post-training survey that included identical knowledge, attitude, and behavior questions as on the pre-training survey. Pre- and post-training surveys were linked using unique identifiers so that responses could be compared directly.

Day visitors and campers were invited to voluntarily participate in a parallel survey. To promote the survey for visitors, flyers were posted at trailheads, the campsite check-in, bathrooms, picnic areas, and other locations inside park headquarters and at the ranger station. Flyers were also carried by roving rangers from July to October 2010. The flyers included a link to the online survey and indicated the four park locations where paper surveys and the disclosure statement were available. The survey link was also displayed on the park Web site. To capture potential tick-borne disease exposure during their park visit, day visitors and campers were requested to complete their surveys approximately one month after their visit. Campers could voluntarily provide an e-mail address at check-in to receive a reminder to complete the follow-up survey. Surveys were also distributed during park events such as weekly bike races.

Analyses were conducted using SAS (SAS. 2011. SAS Version 9.3. SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, North Carolina, USA) and Excel (Excel. 2010. Microsoft Office 2010. Microsoft, Redmond, Washington, USA). Linked responses for the pre- and post-training surveys were compared using McNemar’s exact test. Responses for day visitors and campers are presented jointly when there was no statistically significant difference between the two groups at the 95% confidence level using chi-square and Fisher’s exact tests. Relative risk (RR) was calculated to determine magnitude of difference in outcomes between two groups. All P-values were two-sided with statistical significance evaluated at the 0.05 α level. Records with missing data were excluded from analysis.

Results

Employees

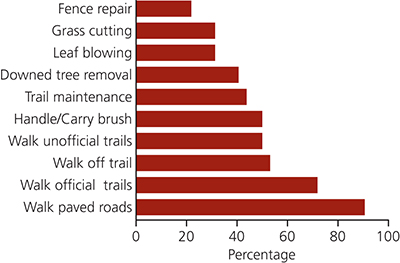

Thirty-two park employees completed the pre-training survey. Twenty-six (81.3%) were male, 23 (71.8%) were more than 45 years of age, and 20 (64.5%) reported that they had worked for Greenbelt Park for 10 or more years (table 1). Most employees had at least one exposure to tick habitat per week. The most frequently reported activities with a high likelihood of tick exposure included walking off trail (n = 17, 53.1%) and carrying brush (n = 16, 50.0%; fig. 3). Twenty-four (75.0%) employees reported finding at least one unattached (nonbiting) tick on their body during the past year and 22 (68.8%) reported finding attached ticks at least once in the past year.

| Table 1. Characteristics of Greenbelt Park employee survey respondents, 2010 | ||

|---|---|---|

| Category | Number | Percentage |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 26 | 81.2 |

| Female | 6 | 18.8 |

| Age (years)* | ||

| <35 | 5 | 16.1 |

| 35–44 | 3 | 9.7 |

| 45–54 | 13 | 41.9 |

| >55 | 10 | 32.3 |

| Employment Status | ||

| Full-time | 23 | 71.8 |

| Seasonal | 4 | 12.5 |

| Volunteer/Intern | 5 | 15.6 |

| Length of Employment* | ||

| <1 | 1 | 3.2 |

| 1–2 | 7 | 22.6 |

| 3–5 | 3 | 9.7 |

| 6–10 | 0 | 0 |

| >10 | 20 | 64.5 |

| Hours Worked Outdoors During Average Week* | ||

| None | 1 | 3.6 |

| <10 | 3 | 10.7 |

| 10–20 | 5 | 17.9 |

| 21–30 | 3 | 10.7 |

| 31–40 | 14 | 50 |

| >40 | 2 | 7.1 |

| Note: Total sample = 32. *Missing data excluded. |

||

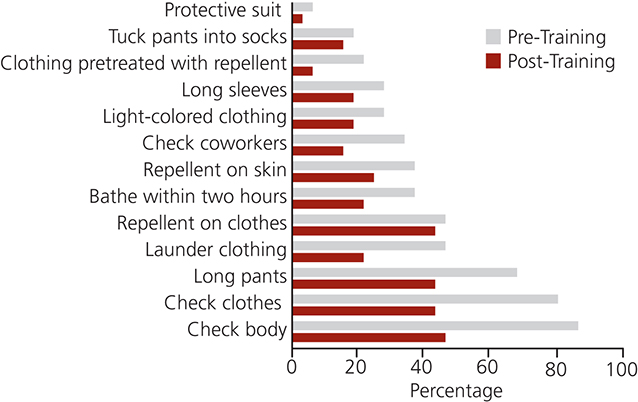

Three preventive measures were frequently reported in the pre-training survey. Twenty-two employees (68.8%) reported wearing long pants as part of the NPS uniform, 26 (81.3%) usually or always checked their clothing, and 28 (87.5%) checked their bodies for ticks after working outdoors. All of the other preventive measures were used by less than half of the respondents. Less than half usually or always used other clothing (long pants, socks, and sleeves) or repellent preventive measures (permethrin-impregnated clothing, skin treatment; fig. 4). When asked why they did not take preventive measures more often, four (12.5%) reported that it was too hard to remember to check for ticks, three (9.4 %) reported that they were unaware of clothing prevention measures, and two (6.3%) reported that uniform requirements did not allow clothing-related prevention measures. Employees reported not taking repellent-related prevention measures because they did not like the way repellent smelled or felt (n = 6, 18.8%), they were concerned about repellent safety (n = 4, 12.5%), it was hard to remember to use repellent (n = 4, 12.5%), and they were unaware of repellent-based preventive measures (n = 3, 6.3%).

Of the 32 employees who completed the pre-training survey, five (15.6%) reported a previous Lyme disease diagnosis and all five were diagnosed at the same time they were working for Greenbelt Park. No new diagnoses of tick-borne disease were reported on the post-training survey. Three of the previously infected employees worked in the Division of Interpretation with the role of interacting with the visitors and campers, one employee worked for the Facility Management Division and had frequent direct exposure to tick habitat, and one at the regional office had no exposure to tick habitat. Three reported working outdoors 10–20 hours per week, one reported working outdoors 31–40 hours, and one reported working outdoors for less than 10 hours per week. The employees with previous Lyme disease were more likely to tuck their pants into socks than those without a history of Lyme disease (p = 0.0039). They were not, however, significantly more likely to employ repellent-based or tick check–based preventive measures or to avoid activities in the park known to be of high risk for tick encounters.

NPS Photos (3)

When responses from all 32 pre-training surveys were compared with the 19 post-training surveys, unlinked analysis demonstrated that knowledge improved for many questions. Employees were 5.6 (95% confidence interval [CI], range = 1.8–18.0) times more likely to answer correctly on the post-survey that ehrlichiosis is another tick-borne disease, and 2.0 (95% CI, range = 0.4–10.9) times more likely on the post-survey to answer correctly that the correct way to remove a tick is to pull it straight out using tweezers. Employees were 2.3 (95% CI, range = 1.4–3.9) times more likely to answer correctly on the post-survey than on the pre-survey that a tick must be attached for at least 24 hours for transmission of the bacterium that causes Lyme disease. Employees were less likely (relative risk ratio [RR] = 0.8, 95% CI, range = 0.4–1.7), however, to answer correctly on the post-survey that the red bull’s-eye rash is not always present with Lyme disease. Employees were equally likely to answer correctly on both surveys (RR = 1.0, 95% CI, range = 0.8–7.4) that Greenbelt Park provided information about tick-borne disease prevention (fig. 5). Similarly, the vast majority of employees responded correctly on both surveys that the park provided repellent for employees (RR = 1.1, 95% CI, range = 0.9–1.3). Most employees before and after the training felt that Lyme disease was a somewhat to very serious problem at Greenbelt Park (93.4% pre-training and 94.5% post-training) and felt that it was somewhat to very likely that they would acquire Lyme disease or another tick-borne disease while employed at Greenbelt Park (87.1% pre-training and 89.0% post-training). A linked analysis comparing the responses of the 19 employees who completed both pre- and post-training surveys confirmed similar results for knowledge and no significant difference in attitudes.

Day visitors and campers

Between 2 July and 1 September 2010, 180 surveys were completed by 127 day visitors and 53 campers (table 2); most completed the survey online. Of the 81 day visitors (64%) who provided a departure date, 30 (37.1%) responded to the survey on their departure date and 14 (17.3%) responded more than 30 days after departure; only nine campers (17.0%) completed the survey one month after their visit. Despite the instructions to wait 30 days from their park visit to complete the survey (to capture any tick-borne disease), 67 (82.7%) of 81 day visitors who reported a departure date and survey completion date completed surveys less than 30 days from their visit.

| Table 2. Characteristics of day visitor and camper survey respondents at Greenbelt Park, 2010 | ||

|---|---|---|

| Category | Number | Percentage |

| Use | ||

| Day visitor | 127 | 70.6 |

| Camper | 53 | 29.4 |

| Origin* | ||

| U.S. Resident | 156 | 90.7 |

| International | 16 | 9.3 |

| Survey Type | ||

| Online survey | 132 | 73.4 |

| Paper survey | 48 | 26.7 |

| Reported6782.7 | ||

| Follow-up survey (campers only, n = 53) | 9 | 17.0 |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 96 | 53.5 |

| Female | 84 | 46.7 |

| Age (years) | ||

| <18 | 6 | 3.3 |

| 18–24 | 14 | 7.8 |

| 25–34 | 35 | 19.4 |

| 35–44 | 44 | 24.0 |

| 45–54 | 47 | 26.1 |

| >55 | 34 | 18.9 |

| How much of day spent in the park* | ||

| Greater than or equal to half | 37 | 40.2 |

| Less than half | 55 | 59.8 |

| Note: Total sample = 180. *Missing data excluded. |

||

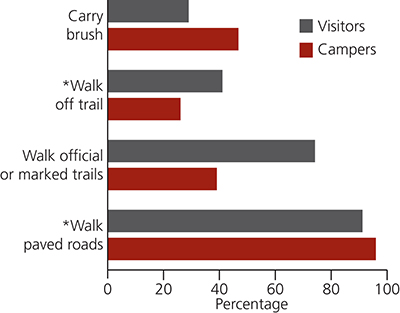

Over half of respondents were male (n = 96, 53.5%) and 81 (45.0%) were at least 45 years of age. Most day visitors and campers had at least one type of exposure to tick habitat. Of those who responded, the most frequently reported outdoor activities with high likelihood of tick exposure included walking on trails (72 day visitors [74.2%] and 18 campers [39.1%]) and carrying brush (27 day visitors [29%] and 22 campers [46.8%]; fig. 6). Forty-six day visitors (41%) and six campers (6.7 %) found at least one unattached tick from their visit to Greenbelt Park, while 41 day visitors (45%) and three campers (12%) found at least one tick attached to them. Neither campers nor day visitors reported a new Lyme disease diagnosis after visiting the park, although 14 (7.8%) reported a previous Lyme disease diagnosis. Those with a previous history of tick-borne disease were no more likely to employ repellent-based (p = 0.9408) or tick check–based (p = 0.8013) preventive measures than campers and day visitors without a history of tick-borne disease.

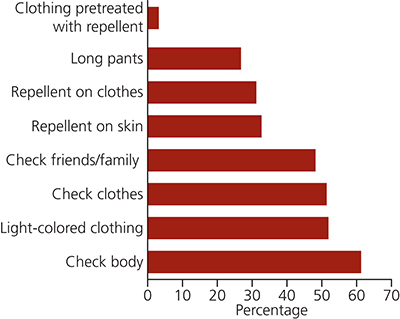

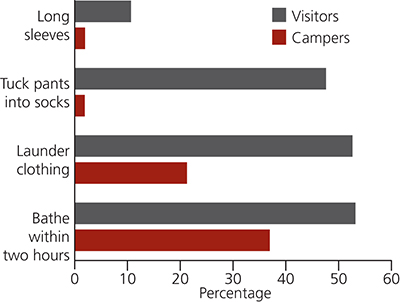

For many preventive measures, there were no significant differences between campers and day visitors (fig. 7). Of those campers and day visitors who responded, 85 (47.2%) usually or always used more than one repellent-based preventive measure per visit and 141 (78.3%) usually or always used more than one clothing-based preventive measure. There were, however, significant differences between behaviors for laundering clothing, bathing within two hours, wearing long sleeves, and tucking pants into socks or boots (fig. 8). In all of these cases day visitors were more likely than campers to employ the preventive measures. When asked why they did not use preventive measures, 93 day visitors and campers (51.6%) responded that it was too hot to wear long sleeves and pants tucked into socks, 28 (15.6%) responded that they did not like the way repellent smelled and felt, 39 (21.7%) were concerned about pesticide safety, and 15 (8.3%) indicated that it was too hard to remember to check themselves for ticks. Only seven day visitors (5.5%) reported being unaware of the tick checking method of prevention compared with 11 (20.7%) campers.

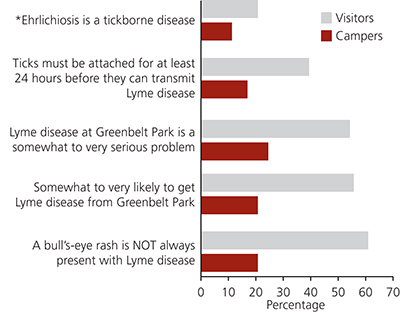

Slightly more than half of day visitors (n = 59, 55.7%) and about a fifth of campers (n =11, 20.8%) responded that they thought it was somewhat to very likely they would acquire Lyme disease from being in Greenbelt Park (RR = 2.7, 95% CI, range = 1.5–4.7; fig. 9). Day visitors were 2.2 (95% CI, range = 1.3–3.7) times more likely than campers to feel that Lyme disease at Greenbelt Park was a serious problem. Day visitors were 2.3 (95% CI, range = 1.2–4.4) times more aware than campers that ticks must be attached for longer than 24 hours to transmit Lyme disease and 2.9 (95% CI, range = 1.7–5.1) times more aware that a bull’s-eye rash does not always accompany Lyme disease infection. Less than a quarter of day visitors (n = 22, 20.8%) and campers (n = 6, 11.32%) were aware that ehrlichiosis is another tick-borne disease affecting residents in Maryland.

Discussion

We learned that employees are concerned about ticks and Lyme disease, that their job activities frequently require them to work outdoors and in tick habitat during months when there are high nymph populations, and that the educational training for employees was effective in increasing knowledge of ticks and tick-borne diseases. Despite increased awareness that Lyme disease was a problem in Greenbelt Park and that certain work activities increased employees’ risk of exposure, the intervention did not effectively increase the use of even the simplest of preventive measures such as checking oneself after going into tick habitat. This highlights the difficulty of behavioral change and emphasizes that a single training is not enough to influence daily tick checking and maintaining behavioral change.

Day visitors and campers also encountered ticks and participated in activities that took them into tick habitat. We did not receive any reports of tick-borne illness through the survey, possibly because most day visitor and camper respondents did not wait at least 30 days to return their survey. This is the minimum time needed to account for the incubation period of Lyme disease plus time for physician diagnosis. Although day visitors perceived that Lyme disease was a problem in the park, half or less of the day visitors reported using protective measures when they were in the park. Paradoxically, day visitors had greater knowledge and implemented more protective measures than campers, even though day visitors spent the shortest time in the park and had relatively little exposure to ticks. Campers also presumably have a relatively increased risk of exposure because of activities such as gathering wood for campfires and clearing brush from campsites. This suggests that campers should be targeted for educational messages through methods such as ranger-led interpretive talks, reminders by rangers on campsite rounds, and online tick-borne disease information for campers making reservations online (Wong and Higgins 2010). Targeted messaging and communication strategies should be developed for different audiences.

That 15% of employees reported contracting Lyme disease while employed at Greenbelt Park demonstrates that the risk is real and is consistent with other reports of occupational risk for Lyme disease (Adjemian et al. 2012; Han et al. 2014; Smith et al. 1988). Employees and park visitors with a prior Lyme disease diagnosis were no more likely to employ protective measures than those who did not report prior Lyme disease. Variability in adherence to personal protective measures to prevent Lyme disease has also been documented previously (Gould et al. 2008; Hayes and Piesman 2003; Phillips et al. 2001; Smith et al. 2001; Vázquez et al. 2008).

Similar to other studies, our findings suggest that knowledge does not always translate to implementation of personal protective measures. However, these low-cost approaches to educate the public, especially if they address knowledge gaps such as those we identified, should not be dismissed, because they do have positive effect. Alternative approaches to reduce the risk of tick encounters should be developed in place of using pesticides that are unpleasant in feel and smell, including measures that rely less on individual motivation and actions or practices with low compliance. Incorporating permethrin-impregnated clothing into uniform requirements for park employees, and increasing the availability of permethrin-impregnated clothing and socks in appropriate fabrics for hot and humid temperatures where Lyme disease is endemic might be an effective way to protect employees. Park managers, for example, made both repellents and permethrin-impregnated socks available to employees immediately after the training. The National Park Service protects the natural ecosystems of its parks with minimal interference. Thus, implementing environmental controls such as widespread application of pesticide to reduce tick populations, exclusion of deer and other Lyme disease vectors, and treatment of tick hosts are generally not viable options to reduce the risk of human tick-borne disease in national parks, according to management policies.

National parks present unique environments for zoonotic disease transmission because of the abundance of fauna and because high-risk behaviors are conducted, often without adequate knowledge of public health risks. Because there were few reports of prior Lyme disease diagnosis and no reports of new diagnoses from the survey, our ability to analyze risk factors for disease was limited. Behaviors were self-reported and could not be validated. The day visitors and campers who responded to our survey were a convenience sample and may not represent the true nature of the visitor and camper population at the park, but these results do provide the best data available. Finally, while survey respondents provided insights regarding activities conducted within the park, they might also have additional potential to develop diseases from tick exposures outside of the park.

Conclusions

We learned that respondents with previous Lyme disease diagnosis will tuck in their pants more often than those without a previous diagnosis, and that day visitors are more aware of the risk than campers who tend to travel the farthest. The lack of other correlations provides numerous opportunities for education, including messaging to change behaviors and fill knowledge gaps. Even with knowledge of the risk, individuals are reluctant to implement personal protective measures, highlighting the difficulty of implementing interventions effectively to change health behaviors. These results and implications support the need for continued efforts to increase and monitor tick-borne disease prevention behaviors and knowledge among park visitors and employees alike.

Acknowledgments

This study would not have been possible without the active involvement of S. B. Wee, Kimberly Mitchell, Rene Najera, Byron Pugh, and Kis Robertson, Maryland Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, Center for Zoonotic and Vectorborne Diseases; Ellen Stromdahl, U.S. Army Public Health Command, Entomological Sciences Program; Eli Alfred, Major Horsey, Robin Martin, and other staff of Greenbelt Park, National Park Service; and John Carroll, United States Department of Agriculture, Agriculture Research Service. And a special thank you to George Han, epidemic intelligence officer, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The DHMH Institutional Review Board approved the methodology (protocol 10-22) and the National Park Service provided a permit (NACE-2010-SCI-0019) to conduct the study. This study was supported in part by an appointment to the Applied Epidemiology Fellowship Program administered by the Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists and funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Cooperative Agreement #1U38HM000414. The findings and conclusions are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, U.S. Army, or National Park Service.

References

Adjemian J., I. B. Weber, J. McQuiston, K. S. Griffith, P. S. Mead, W. Nicholson, A. Roche, M. Schriefer, M. Fischer, O. Kosoy, J. J. Laven, R. A. Stoddard, A. R. Hoffmaster, T. Smith, D. Bui, P. P. Wilkins, J. L. Jones, P. N. Gupton, C. P. Quinn, N. Messonnier, C. Higgins, and D. Wong. 2012. Zoonotic infections among employees from Great Smoky Mountains and Rocky Mountain National Parks, 2008–2009. Vector-Borne and Zoonotic Diseases 12:922–931.

Centers for Disease Control (CDC). 2015. Lyme disease data, statistics, and data file. Accessed 7 October 2015 from http://www.cdc.gov/lyme/stats/index.html.

Eisen, L., D. Wong, V. Shelus, and R. J. Eisen. 2013. What is the risk for exposure to vector-borne pathogens in the United States national parks? Journal of Medical Entomology 50:221–230.

Gould, L. H., R. S. Nelson, K. S. Griffith, E. B. Hayes, J. Piesman, P. S. Mead, and M. L. Cartter. 2008. Knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors regarding Lyme disease prevention among Connecticut residents, 1999–2004. Vector-Borne and Zoonotic Diseases 8:769–776.

Han, G. S., E. Y. Stromdahl, D. Wong, and A. C. Weltman. 2014. Exposure to Borrelia burgdorferi and other tick-borne pathogens in Gettysburg National Military Park—South-central Pennsylvania, 2009. Vector-Borne and Zoonotic Diseases 14(4):227–233.

Hayes, E. B., and J. Piesman. 2003. How can we prevent Lyme disease? New England Journal of Medicine 348:2424–2430.

Phillips, C. B., M. H. Liang, O. Sangha, E. A. Wright, A. H. Fossel, R. A. Lew, K. K. Fossel, and N. A. Shadick. 2001. Lyme disease and preventive behaviors in residents of Nantucket Island, Massachusetts. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 20:219–224.

Smith, G., E. P. Wileyto, R. B. Hopkins, B. R. Cherry, and J. P. Maher. 2001. Risk factors for Lyme disease in Chester County, Pennsylvania. Public Health Reports 116:146–156.

Smith, P. F., J. L. Benach, D. J. White, D. F. Stroup, and D. L. Morse. 1988. Occupational risk of Lyme disease in endemic areas of New York State. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 539:289–301.

Vázquez, M., C. Muehlenbein, M. Cartter, E. B. Hayes, S. Ertel, and E. D. Shapiro. 2008. Effectiveness of personal protective measures to prevent Lyme disease. Emerging Infectious Diseases 14:210–216.

Wong, D., and C. L. Higgins. 2010. Park rangers as public health educators: The Public Health in the Parks Grants Initiative. American Journal of Public Health 100:1370–1373.

About the authors

At the time of this study Erin H. Jones was a recipient of the Applied Epidemiology Fellowship funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Council of State and Territorial Health Officials located at the Maryland Department of Health and Mental Hygiene in Baltimore, Maryland. She then worked for three additional years with the Maryland Department of Health and now is with Clinical RM, Inc. Her primary research interests include the occurrence, transmission, and prevention of zoonotic diseases. Amy Chanlongbutra and David Wong are epidemiologists with the National Park Service, Office of Public Health. Fred Cunningham was the superintendent of Greenbelt Park, National Park Service. Katherine A. Feldman was and still is the State Public Health Veterinarian at the Maryland Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. Please direct correspondence to Erin Jones.

Data for figures 3, 4, 6, 7, 8, and 9

| Figure 3 (data table). Percentage of employees with exposure to a given outdoor habitat or activity at least once a week | |

|---|---|

| Category | Percentage |

| Fence repair | 21.9 |

| Grass cutting |

31.3 |

| Leaf blowing | 31.3 |

| Downed tree removal | 40.6 |

| Trail maintenance | 43.8 |

| Handle/carry brush | 50.0 |

| Walk unofficial trails | 50.0 |

| Walk off trail | 53.1 |

| Walk official trails | 71.9 |

| Walk paved roads | 90.6 |

| Figure 4 (data table). Percentage of employees who usually or always used selected tick prevention measures prior to and one month following an educational training on ticks and tick-borne disease prevention | ||

|---|---|---|

| Practice | Pre-Training | Post-Training |

| Protective suit | 6.3 | 3.1 |

| Tuck pants into socks | 18.8 | 15.6 |

| Clothing pretreated with repellent | 21.9 | 6.3 |

| Long sleeves | 28.1 | 18.8 |

| Light-colored clothing | 28.1 | 18.8 |

| Check coworkers | 34.4 | 15.6 |

| Repellent on skin | 37.5 | 25.0 |

| Bathe within two hours | 37.5 | 21.9 |

| Repellent on clothes | 46.9 | 43.8 |

| Launder clothing | 46.9 | 21.9 |

| Long pants | 68.8 | 43.8 |

| Check clothes | 81.3 | 43.8 |

| Check body |

87.5 |

46.9 |

| Figure 6 (data table). Percentage of day visitors (n = 127) and campers (n = 53) who always or usually took tick prevention measures during their visit were significantly different between the two groups, Greenbelt Park, 2010 | ||

|---|---|---|

| Activity | Visitors | Campers |

| Carry brush | 29.0 | 46.8 |

| *Walk off trail | 41.1 | 26.1 |

| Talk official or marked trails | 74.2 | 39.1 |

| *Walk paved roads | 91.2 | 96.0 |

| *Difference is significant. | ||

| Figure 7 (data table). Percentage of day visitors and campers combined (n = 180) who always or usually took tick prevention measures during their visit to Greenbelt Park, 2010 | |

|---|---|

| Prevention Behavior | Visitors and Campers Combined |

| Clothing pretreated with repellent | 3.2 |

| Long pants | 26.8 |

| Repellent on clothes | 31.2 |

| Repellent on skin | 32.7 |

| Check friends/family | 48.2 |

| Check clothes | 51.4 |

| Light-colored clothing | 51.9 |

| Check body | 61.3 |

| Figure 8 (data table). There were statistically significant differences between day visitors (n = 127) and campers (n = 53) who always or usually took the four tick prevention measures during their visit to Greenbelt Park, 2010 | ||

|---|---|---|

| Prevention Measures | Visitors | Campers |

| Long sleeves | 10.7 | 2.0 |

| Tuck pants into socks | 47.6 | 1.9 |

| Launder clothing | 52.6 | 21.3 |

| Bathe within two hours | 53.2 | 37.0 |

| Figure 9 (data table). Percentage of day visitors (n = 127) and campers (n = 53) who responded correctly to knowledge and attitude questions at Greenbelt Park, 2010 | ||

|---|---|---|

| Statement/Perception | Visitors | Campers |

| Ehrlichiosis is a tickborne disease* | 20.8 | 11.3 |

| Ticks must be attached for at least 24 hours before they can transmit Lyme disease | 39.4 | 17.0 |

| Lyme disease at Greenbelt Park is a somewhat to very serious problem | 54.3 | 24.5 |

| Somewhat to very likely to get Lyme Disease from Greenbelt Park | 55.7 | 20.8 |

| A bulls-eye rash is NOT always present with Lyme disease | 61.0 | 20.8 |

| *Note: The differences in responses for knowledge about ehrlichiosis were not statistically significant. | ||

Download: PDF of this article

This article published

Online: 6 May 2016; In print: 25 March 2016

URL

https://www.nps.gov/ParkScience/articles/parkscience32_2_46-53_jones_et_al_3835.htm

Suggested citation

Jones, E. H., A. Chanlongbutra, D. Wong, F. Cunningham, and K. A. Feldman. 2016. Knowledge, attitudes, and practices regarding Lyme disease prevention among employees, day visitors, and campers at Greenbelt Park. Park Science 32(2):46–53.

This page updated

5 May 2016

Site navigation

• Back to Volume 32, Number 2

• Back to Park Science home page

Last updated: August 9, 2018