Part of a series of articles titled Park Paleontology News - Vol. 09, No. 2, Fall 2017.

Previous: Park Paleontologist Retires

Article

Mural by Kaern Carr.

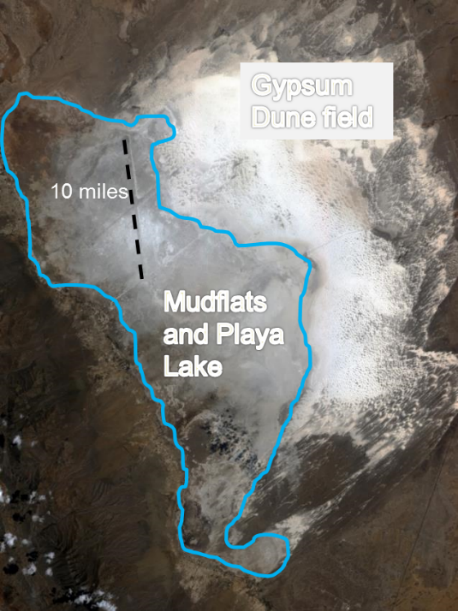

Base photo courtesy of NASA.

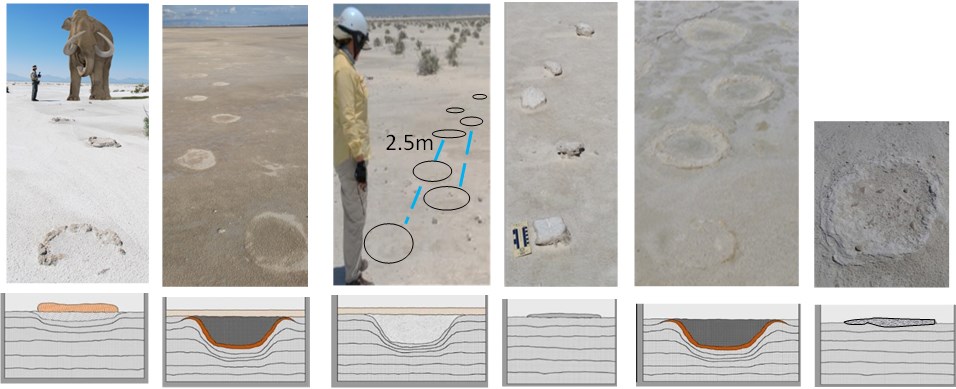

NPS photos.

NPS photos.

These fossil tracks have unusual preservation in soft gypsiferous lacustrine and playa lake-margin sediments. Prints are preserved in soft gypsum and carbonate sediment, making them extremely fragile and susceptible to rapid weathering once exposed. Some prints and trackways have an ephemeral expression, only visible when sediment moisture is high enough to create a contrast with surrounding sediment. The ephemeral expression is believed to be related to texture differences from the print infill and the surrounding sediment. As the surface becomes wet or dry, prints absorb or release moisture at different rates than the surrounding sediment, allowing prints to disappear and reappear as conditions changes; at times salts will form at the outer edges of the prints.

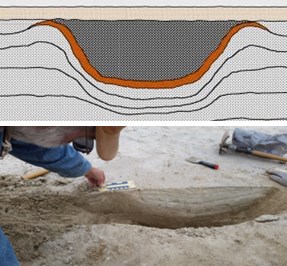

NPS Photo and graphic.

The prints can be raised above or depressed below the surface. We interpret the raised tracks to represent compressed sediment from below the track being exposed by wind erosion and, in some cases, affected by diagenetic alteration or precipitation of dolomite. Sediment that infills the tracks includes fine-grained or coarse-grained gypsum sand, siliciclastic mud, and dolomite. Many tracks are very fragile, but those comprised of dolomite are comparatively resistant. Less obvious are tracks that are present as shallow surface depressions. Sediment surrounding these tracks are distorted as seen in natural vertical exposures or excavations into track-bearing strata.

NPS photos and graphics.

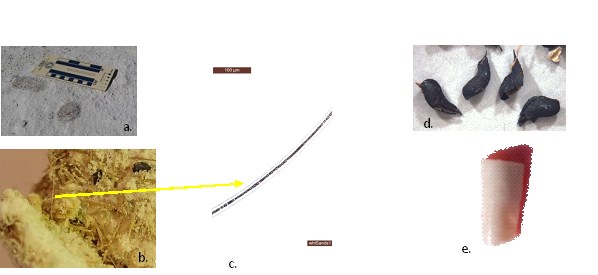

In addition to the prints, layers of vegetation have been found preserved beneath and above many of the tracks, and hair and possible coprolites have also been found in association with the trackways.

a., b., and e. NPS photos; d. USGS photo; and c. USFWS photo.

Although the monument has a very small resource staff (two FTE), it has had incredible support from the NPS Intermountain Region and WASO, and great partnerships with many universities within the U.S. and the U.K., and federal and state agencies. This survey continues to discover new trackways as they are exposed from eroding sediment. This study is part of an ongoing effort to catalog and correlate sediments and trackways at White Sands National Monument to better plan for their preservation and interpretation.

Part of a series of articles titled Park Paleontology News - Vol. 09, No. 2, Fall 2017.

Previous: Park Paleontologist Retires

Last updated: April 22, 2020