Last updated: April 7, 2023

Article

Designing the Desert: Landscape & the Painted Desert Community Complex

NPS / Beinlich

National parks in the southwestern U.S. are renowned for their grand landscapes, outstanding natural formations, and associations with indigenous peoples. The vernacular buildings that comprise the region’s ranches, prehistoric dwellings, trading posts, and colonial sites reveal how people lived and worked on the land. In contrast are the modernist visitor center landscapes that were designed as part of the National Park Service’s Mission 66 program. Petrified Forest National Park’s Painted Desert Community Complex (PDCC) is one of them.

The Petrified Forest was proclaimed a national monument by President Theodore Roosevelt in 1906, recognizing the area’s uniqueness as the world’s largest repository of petrified wood. Public access to the remote site was improved when Route 66 was established in the mid 1920’s. The federal highway passed north of the monument and connected Chicago to Los Angeles with some 400 miles of road through Arizona.

To capitalize on the increased traffic through the region, local resident Herbert Lore built the Stone Tree House out of petrified wood just off Route 66. The lodge and trading post, later renamed the Painted Desert Inn, became a popular stop for tourists and locals. Its isolated but accessible location proved to be a boon for business when the monument was expanded northward in 1931 to include the Painted Desert. By 1950, park planners formally identified the need to locate a new headquarters in the north section of the park. Converting the Painted Desert Inn to meet this need was considered but ultimately rejected. By the end of the decade a new idea about park planning had taken hold that would be realized on an undeveloped site just south of the Inn.

Mission 66 & the NPS Visitor Center

The years after World War II saw an increasingly mobile population put tremendous strain on a national park system that was ill-equipped to handle the influx of visitors. Visitation rose from 3,500,000 to 30,000,000 between 1931 and 1948 while investment in parks’ infrastructure and staffing had languished since the 1930s. In response to this crisis, NPS Director Conrad Wirth promoted a 10-year funding program to modernize park facilities in the lead up to the agency’s 50th anniversary in 1966. The Mission 66 program was intended to improve the visitor experience by bringing park infrastructure and amenities up to contemporary standards while simultaneously conserving natural resources.To meet this dual objective, a new type of building was envisioned. The NPS visitor center was born out of a need to orient visitors to the park while managing their access. A central starting point was intended to reduce unpredictable traffic patterns and prevent damage to the park. In additional, the visitor center was intended to present a modern image of the National Park Service to the 80 million visitors expected by 1966. A total of 109 visitor centers were planned for construction as part of the Mission 66 program.

Painted Desert Community Complex - Entry

Left image

The Painted Desert Community Complex as viewed from the parking lot entrance in 1962.

Credit: NPS / Beinlich

Right image

The same view of the entrance in 2017.

Credit: NPS / J. Holgerson

The Central Plaza

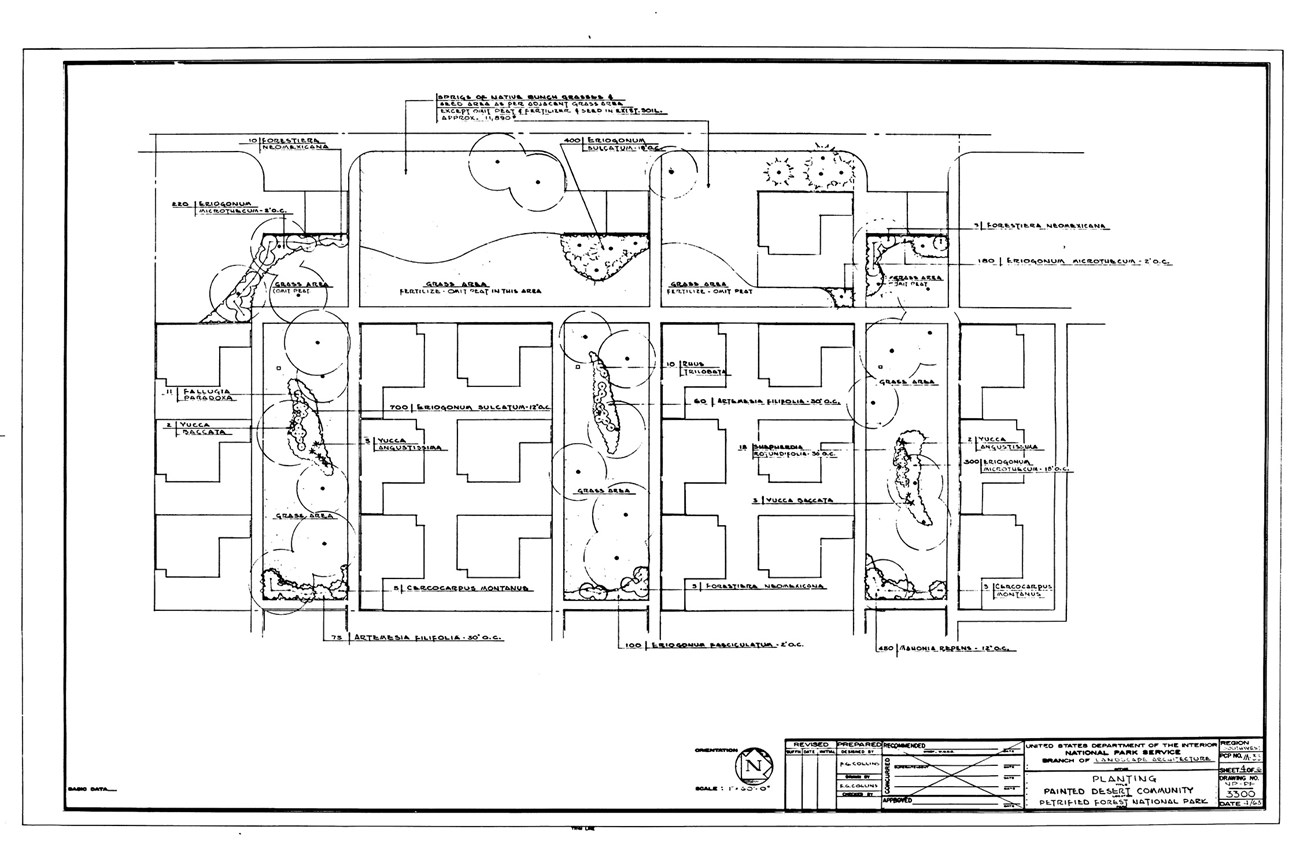

The central plaza lies at the heart of the complex and is enclosed on three sides by the visitor center, apartment wing, and concession building. Viewed from the visitor center’s entrance, the plaza appears as a respite from the open road with trees, shrubs, and a reflecting pool at the far corner. Beyond a free-standing seat wall made of Arizona sandstone, the plaza’s east side blends into an Open Area that was intended for interpreting native vegetation to the public. That use was not realized until recently when the park installed a short loop trail with interpretive signage. The Open Area continues to provide a transition from the central plaza’s public area to the private park residences that lie beyond it.The plaza’s plantings were intended to showcase flora that descended from the area’s prehistoric condition, connecting the park’s lush Triassic past to the arid present. Two specimens of monkey puzzle trees (Araucaria araucana) were ordered from Chile but did not survive the journey. The concept was scaled back in a 1962 plan that shows a “Triassic swamp exhibit” next to the reflecting pool, an exhibit of petrified wood, and two ginkgo trees (Ginkgo biloba) along with other trees and plants. By 1963, an updated plan retained the petrified wood display and one of the ginkgo trees but the swamp and other references to the Triassic period were eliminated in favor of a more general “oasis” concept characterized by non-native ornamentals. Outside the plaza, native plants such as Oneseed juniper (Juniperus monospernum), rabbitbrush (Ericameria nauseosa), Mormon tea plant (Ephedra torreyana), and various yuccas grounded the designed landscape in its regional setting.

Residential Courtyards

At the plaza’s southeast corner the area narrows into a concrete walkway that leads to the residential area of the complex. A canopy covers the sidewalk and provides protection from the sun and seasonal rains. Stands of cottonwoods (P. fremontii, P. acuminata) and pinyon pines (Pinus edulis) were specified to reinforce the change of setting and provide shade and privacy throughout the residential area and trailer park.

NPS

Mission 66: Modern Design Beyond Petrified Forest

Mission 66 visitor centers were intended to function as the hub of the park, but aspirations for the new headquarters at Petrified Forest reached even farther. The Painted Desert Community Complex was envisioned as an "Information Center" for all areas of the National Park System, and it was the first of its kind designed to introduce visitors to the concept of national parks and to parks around the country.The Mission 66 program expanded and standardized visitor services by providing the basic information, visitor facilities, and interpretive programs that remain an essential part of a national park experience. In choosing Neutra and Alexander as architects of the Painted Desert Community Complex, the National Park Service fully accepted modern architecture for the Mission 66 program.

- National Park Service Mission 66 Era Resources - National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form