Soldiers in the field often suffered from a lack of food and supplies. Organizations, like the Sanitation Commission, and the civilians that were behind these organizations were truly needed to help with the soldiers everyday needs but also once they were injured or sick. Women, like Clara Barton, made it mission during the Civil War to make an impact on those who were fighting for the cause.

"I may be compelled to face danger, but never fear it, and while our soldiers can stand and fight, I can stand and feed and nurse them." Clara Barton

Clara Barton: Angel of the Battlefield

NPS

Soldiers in the field often suffered from a lack of food and supplies. Clara Barton, a clerk at the Patent Office in Washington, D.C., helped to alleviate this problem, gathering and organizing food and essential items. Risking her life, she took them to the battlefront. On September 17th, 1862, at the Battle of Antietam, Barton provided surgeons with critical supplies, fed and comforted the wounded, and even assisted surgeons during operations. Additionally, she performed minor surgery by removing a bullet from a soldier's cheek with a pocket knife.

Toward the end of the war, Barton was inundated with letters from families and friends of missing soldiers the war department was unable to locate. To further serve the nation, she created with the approval of President Lincoln the Office of the Friends of Missing Soldiers, later renamed the Missing Soldiers Office.

Her search for the missing began at Camp Parole, Maryland, where Union soldiers rehabilitated from their time in Southern prisoner of war camps. Barton operated the Missing Soldiers Office from her boarding house in Washington, D.C. from March 1865 until December 1868. During that time, she received over 63,000 inquiries, located over 22,000 missing soldiers, and helped to organize and establish Andersonville National Cemetery.

After the war, Barton encouraged the United States to sign the treaty proposed at the Geneva Convention in 1864. The treaty dealt with the humane treatment of wounded soldiers, prisoners of war, and civilians during armed conflicts. In 1881, she established the American Association of the Red Cross and was elected president, serving until 1904. Barton died in Glen Echo, Maryland, on April 12th, 1912, and was buried in North Oxford, Massachusetts.

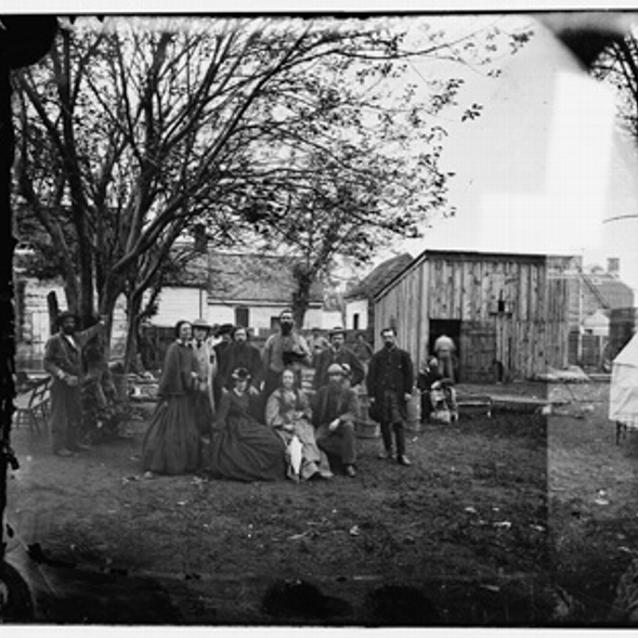

The Sanitation Commission

Library of Congress

Wanting to do more than what could be accomplished through individual efforts, some civilians chose to form medical support organizations. In late April 1861, a group of concerned physicians and citizens met at New York City's Cooper Union to create a national organization dedicated to improving the medical and sanitary conditions within the Union Army. The advisory group hoped to gain the right to investigate and consult the Union Army on medical matters in order to avoid the problems and abuses found in contemporary European wars. After overcoming some initial resistance and agreeing only to be involved with volunteer troops, the group's leadership convinced the Medical Department and the Federal Government of the merits of such a commission. In June 1861, President Lincoln approved the creation of the United States Sanitary Commission.

Shortly after its establishment, the role of the Sanitary Commission changed from being an advisory agency to one involved in major relief activities. What started as an investigation into recruiting practices, diet, camp organization, nursing, and hospital conditions soon evolved into a group active in nearly every aspect of the soldiers' lives. The Commission, aware that many soldiers suffered from poor diet or a shortage of medicines, organized drives to provide the Union Army with supplemental medical supplies, blankets, vegetables, fresh meat, and other essentials.

As originally intended, the Sanitary Commission pressured military authorities to improve the conditions of army camps and taught officers and soldiers the health benefits of proper personal hygiene. The Sanitary Commission continued its mission to supply and advise the Union Army throughout the war, becoming a national voluntary relief agency.

"Our instructions were to accompany the army, and to be ready to render such aid as might be necessary, not only to the really sick and wounded, but to the feeble and to those who were in danger of falling out of the ranks from exhaustion and the want of timely support. Our powers were mainly discretionary, and our wagon was to be regarded merely as the `avant courier' of stores to follow, the supply only to be limited by the demand." - Dr. Lewis H. Steiner, Sanitary Inspector

Part of a series of articles titled A Most Horrid Picture.

Previous: Taking Care of Those in Need

Last updated: August 14, 2017