Last updated: July 19, 2021

Article

The Pioneer Line to California: An Adventure in Transportation

Where there’s gold, there’s opportunity, and the California Gold Rush offered plenty of both.

Thousands of men—potential customers with money in their pockets— would be thronging the Missouri River outfitting towns each spring while the rush lasted. Many would be merchants, doctors, lawyers, teachers, bankers, and hotel-keepers, city men whose life experiences did not prepare them for driving a wagon or packing mules some 2,000 miles across deserts and mountains to California.

So, business idea: sell those men tickets to join a commercial wagon train. Passengers would ride in comfort while experienced staff did the mule-wrangling and driving. Customers would be attended by valets, sleep in coach berths or tents provided by the company, sip wine with their delicious meals, and reach the gold fields in 60 to 70 days—months ahead of everybody else! All for the low, low price of $100 to $300 per person (plus overweight baggage fees).

It seemed too good to be true, and for the most part, it was.

Only one commercial wagon train was ready to roll in 1849, the first year of the rush: the Pioneer Co. of Fast Coaches (known as the Pioneer Line), which was owned, managed, and promoted by a pair of experienced freighters, Thomas Turner and his partner, a man named Allen. Their plan was to provide 20 “handsome carriages,” each drawn by four mules, to carry six men apiece. For hauling baggage and supplies, they’d provide 22 heavy freight wagons. To drive and manage the livestock, they’d hire a 40-man crew. The whole outfit would be guided west by famed mountain man Moses “Black” Harris. At $200 per ticket, Turner and Allen quickly signed up enough passengers for two separate passenger trains. The first would depart on May 15, the other in June.

It seemed like a solid business plan, but then Turner and Allen made some bad mistakes and suffered some bad luck. They bought unbroken mules, and not enough of them. And they overloaded the freight wagons. On his way to meet the wagon train at Independence, Mo., Harris died of cholera, which was raging through the Missouri River towns. Then, the weather on the prairie that spring was horrible, with persistent rain, hailstorms, gales. Mud was deep, rivers in flood. It turned out there were no valets to attend the “gay and festive” passengers, who soon were asked to help harness and drive the wild mules, cook their own meals, and stand guard at night. Eventually they were made to give up their seats and walk. Upon reaching Fort Laramie in eastern Wyoming, Turner made another fateful decision by dumping much of their food, keeping only enough for 60 days.

Mules died. Provisions gave out. Passengers suffered from starvation and scurvy. Many abandoned their baggage and struck out on foot; others were too weak to walk. Twenty-two passengers died, seven of them expiring shortly after reaching Sacramento on October 1. Most of those who stayed with the wagons arrived too crippled to move. One such man, according passenger journals, arrived “drawn up into a kind of ball, and could have been rolled over and over like a bale of carpet.”

The second passenger train rolled into California “in a crippled condition,” as well, and that spelled the end of the Pioneer Line. According to historian Mary McDougal Gordon, a total of 13 more passenger trains set out for California in 1850 and 1852. Only a few, she writes, reached the gold fields; the others broke down along the trail.

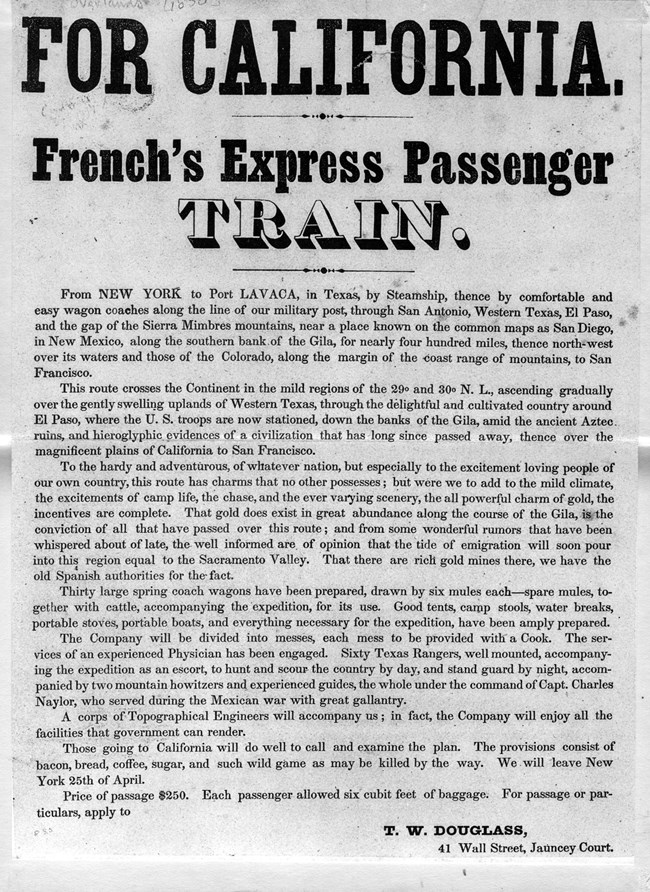

One of the failing 1850 trains was organized by well-known “confidence man” Parker H. French. French promised customers passage by steamer from New York to Port Lavaca, Texas, and thence “by comfortable and easy wagon coaches” across the mild southern climes of Texas to San Francisco. A company of 60 Texas Rangers, he promised, would hunt for the company and stand guard at night with two mountain howitzers. But, pursued by lawmen wanting to arrest him for fraud, French ducked out to Mexico and left his passengers stranded at El Paso without the promised wagons and mules. The company broke up, with men heading in all directions. The first of them to reach San Francisco arrived in mid-December.