Last updated: April 12, 2023

Article

Not to Be Forgotten: Camp Chase Confederate Cemetery (Teaching with Historic Places)

Many, many Confederates were captured whose families have never known their fate, although prayerful diligence was exercised as long as there was a ray of hope. May this list of thousands of names give consolation to mourning hearts, as it will when found that husband, brother or son, having stood by their colors until overwhelming numbers compelled capitulation, and that whatever opportunities for freedom that may have come to him, all were rejected, and he went down to death a faithful Confederate soldier!

Quote from Confederate Veteran magazine, Nashville, TN, January 1898, in reference to the list of the Confederate prisoners of war buried in Ohio.

Today as you pass through the entrance in the stone wall surrounding Camp Chase cemetery, the bustle of Columbus fades behind. Camp Chase encompasses less than two acres, so it is easy to appreciate the entire landscape. More than 2,000 headstones stretch out before your eyes, some so close together they nearly touch. Throughout the cemetery, large old trees with broad canopies offer cool shade on even the hottest summer days. It is hard to imagine that this cemetery was once one of the largest Union Civil War prisoner-of-war camps for thousands of captured troops who served in the Army of the Confederate States of America (CSA).

About This Lesson

This lesson is based on the National Register of Historic Places nomination for Camp Chase Confederate Cemetery (with photographs), Columbus, Ohio, Shriver and Breen's Ohio's Military Prisons in the Civil War, and other sources. The lesson plan was written by Paul LaRue, high school history teacher at Washington Senior High School in Washington Court House, Ohio, with help from the 2003-2004 Research History class students. It was supplemented and edited by the staff of the History Program, National Cemetery Administration, Department of Veterans Affairs, and the Teaching with Historic Places staff. This lesson is one in a series that brings important stories of historic places to the classroom.

Where it fits into the curriculum

Topics: This lesson covers aspects of U.S. history, social studies, Civil War, Reconstruction, and geography. Students will gain an understanding and appreciation for the complex issue of marking graves for Civil War soldiers, especially the prisoner-of-war (POW) populations.

Time period: Civil War Era to 1929

United States History Standards for Grades 5-12

Not to Be Forgotten: Camp Chase Confederate Cemetery

relates to the following National Standards for History:

Era 5: Civil War and Reconstruction (1850-1877)

-

Standard 2B- The student understands the social experience of the war on the battlefield and home front.

-

Standard 3A- The student understands the political controversy over Reconstruction.

-

Standard 3B- The student understands the Reconstruction programs to transform social relations in the South.

Curriculum Standards for Social Studies

National Council for the Social Studies

Not to Be Forgotten: Camp Chase Confederate Cemetery

relates to the following Social Studies Standards:

-

Standard B - The student explains how information and experiences may be interpreted by people from diverse cultural perspectives and frames of reference.

-

Standard E - The student articulates the implications of cultural diversity, as well as cohesion, within and across groups.

Theme II: Time, Continuity and Change

-

Standard B - The student identifies and uses key concepts such as chronology, causality, change, conflict, and complexity to explain, analyze, and show connections among patterns of historical change and continuity.

-

Standard C - The student identifies and describes selected historical periods and patterns of change within and across cultures, such as the rise of civilizations, the development of transportation systems, the growth and breakdown of colonial systems, and others.

Objectives for students

1) To locate POW camps in the North and determine how they rank in population size and mortality rates.

2) To learn about the history of Camp Chase and how its use changed over time.

3) To determine Ohio's role and influence in the creation of a policy by the federal government to recognize the sacrifice of POWs.

4) To outline the evolution of the federal government's policies guiding the marking of POW graves.

5) To design a memorial for veterans buried in their local cemetery.

Materials for students

The materials listed below either can be used directly on the computer or can be printed out, photocopied, and distributed to students. The maps and images appear twice: in a smaller, low-resolution version with associated questions and alone in a larger version.

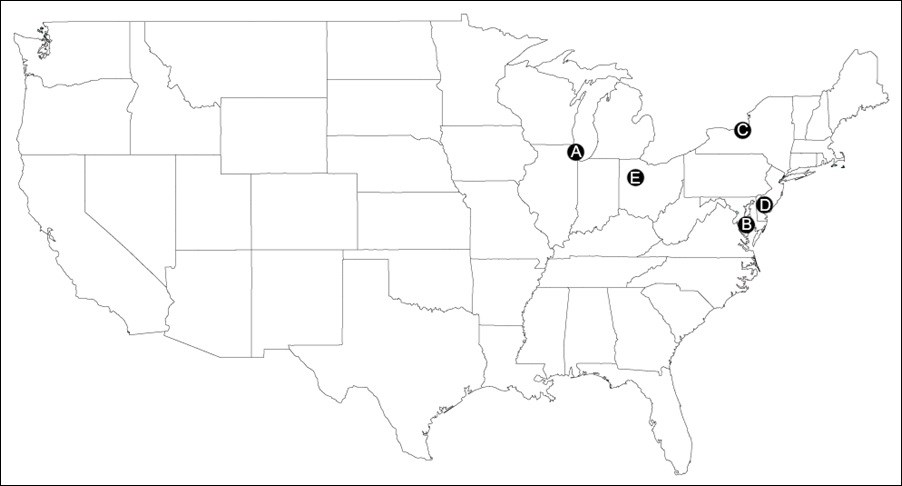

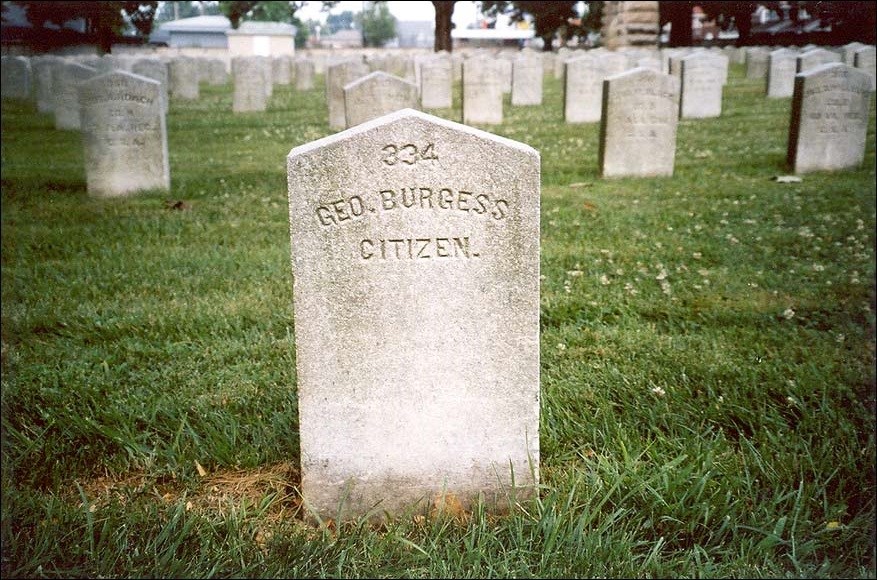

1) one map of Northern prisoner-of-war camps during the Civil War;

2) three readings about Camp Chase Prison and Cemetery: an excerpt from the National Register nomination about Camp Chase, correspondence regarding Confederate POW burials, and an article printed in the Confederate Veteran magazine about the dedication of a Confederate monument at Camp Chase;

3) five photos of Camp Chase Cemetery and its memorial.

Visiting the site

Camp Chase Confederate Cemetery is located at 2900 Sullivant Ave., Columbus, Ohio. It is one of 33 small soldiers' lots and Confederate cemeteries maintained by the National Cemetery Administration (NCA), Department of Veterans Affairs. It is open daily from 8 a.m. to 5 p.m. Camp Chase is not staffed on site and is under the supervision of Dayton National Cemetery. For more information, please contact Dayton National Cemetery, 4100 West Third Street, Dayton, Ohio, 45428, or call 937-262-2115.

|

|

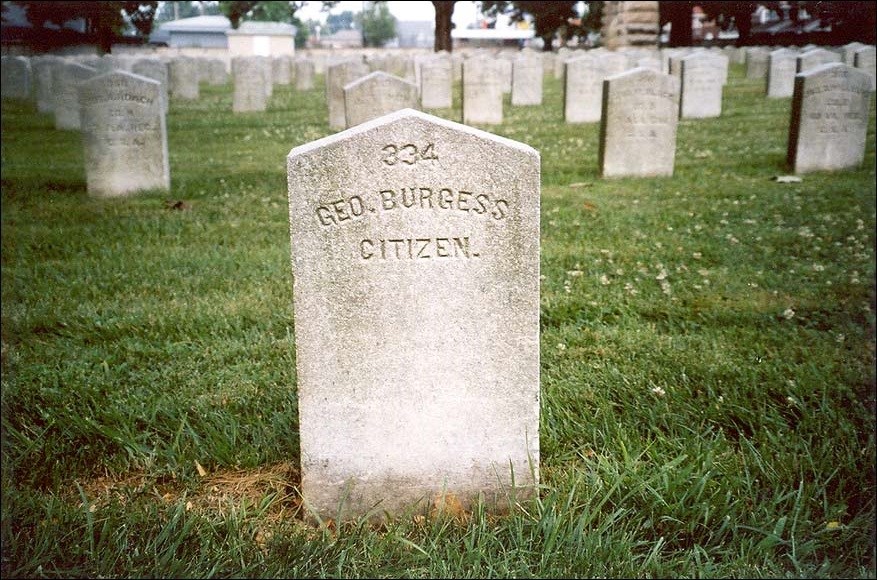

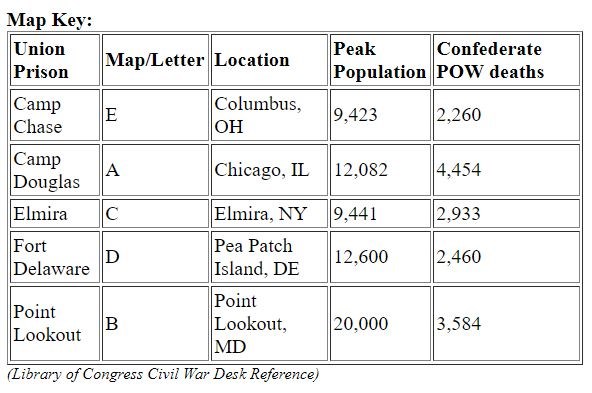

What is unusual about the inscription on this tombstone?

Setting the Stage

When the Civil War began in 1861, no one anticipated a war that would last for several years and cost the lives of nearly 500,000 men. Even less thought was given to prisoners of war. However, by the end of the war over 400,000 Union and Confederate soldiers were held as prisoners of war. In the North the Union Army oversaw 214,865 Confederate prisoners in 78 principal prisons. Prisoners were also held in many other small settings. Of the 194,743 Union prisoners of war, 30,218 died in Confederate prison camps. The 25,976 Confederate prisoners of war who lost their lives in Union camps can be found buried in cemeteries scattered across the north. ¹

The process of marking the graves of Civil War veterans evolved over nearly 70 years. Initially, the federal government focused solely on marking the graves of the Union dead. However, some northern state governments developed independent policies and entitlements for Confederate veterans.

The earliest government mention of marking Confederate graves was 1876 in a report of the Senate Committee on Military Affairs. It discussed the purchase of land for the burial of Confederate prisoners of war. "Should there be other Confederate prisoners who died under similar circumstances, lying buried upon private lands, it is the duty of the Government to make reasonable outlay to secure title to the narrow earth in which their remains do rest."² In 1901, a number of re-interred Confederate remains, as well as several existing graves, at Arlington National Cemetery, Virginia, were the first to be marked with the permanent headstones.

Camp Chase Confederate Cemetery now stands on what was one of the largest Confederate prisoner-of-war camps. Today the graves of the Confederate prisoners of war interred in this small national cemetery are here to tell the story of the treatment of these men and the evolution of the federal government's policy in marking their graves.

¹ Margaret E. Wagner, Gary W. Gallagher, and Paul Finkelman, The Library of Congress Civil War Desk Reference (New York: Simon and Schuster Publishing, 2002), 583-596.

² Final Report of the Commission for Locating and Marking Confederate Graves, 21 February 1916. RG 92, National Archives and Records Administration (NARA).

|

|

Keep in mind that peak population in the above chart means the number provided was the most prisoners at each camp at one time, not the total number of prisoners who passed through each camp during the course of the war.

Questions for Map 1

1. Which camp had the highest number of deaths? Which camp had the highest percentage of deaths?

2. Locate Camp Chase on the map and key. What was the total number of deaths at Camp Chase? How does this number compare with the other Union prisons listed in the chart?

3. Can you think of reasons why a war prison might have such a high death rate?

Determining the Facts

Reading 1: Camp Chase

Camp Chase was one of the five largest prisons in the North for Confederate prisoners of war. Camp Chase's prison population peaked at 9,423 on January 31, 1865. The Army ensured that the graves of those who died were marked with thin headboards and "only the number of the grave and name of its individual occupant;" thus the "graves of the Confederate soldiers were not marked as soldiers, and remained thus inadequately," until the 20th century when Congress approved efforts to recognize the sacrifice of CSA soldiers.¹

The following information is excerpted from the National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form for Camp Chase Site, Columbus, Ohio.

Statement of Significance: Camp Chase was officially dedicated June 20, 1861. It is named in honor of Salmon Portland Chase (1808-1873), former governor of Ohio, the Secretary of the Treasury under President Abraham Lincoln, and later Chief Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court. Initially designated as a training camp for new recruits in the Union Army, Camp Chase was converted to a military prison as the first prisoners of war arrived from western Virginia. In the early months of the Civil War, Camp Chase primarily held political prisoners--judges, legislators and mayors from Kentucky and Virginia accused of loyalty to the Confederacy. In early 1862, Camp Chase served briefly as a prison for Confederate officers. But after a military prison for Confederate officers opened at Johnson's Island, Ohio, Camp Chase housed only non-commissioned officers, enlisted men, and political prisoners.

In February 1862, 800 prisoners of war (officers and enlisted men) arrived at Camp Chase. Included among the 800 Confederate soldiers were approximately 75 African Americans; about half of whom were slaves, the other half being servants to the confederate officers. Much to the horror and dismay of the citizens of Columbus, these men continued to serve their master's in the prison camp. An Ohio Legislative committee was formed and protests over the continued enslavement of these men were sent to Washington D.C. The African Americans were finally released in April and May of 1862; some then enlisted in the Union army.²

According to an exchange agreement reached between North and South on July 22, 1862, Camp Chase was to operate as a way station for the immediate repatriation (return to country of birth or citizenship) of Confederate soldiers. After this agreement was mutually abandoned July 13, 1863, the facility swelled with new prisoners, and military inmates quickly outnumbered political prisoners. By the end of the war, Camp Chase held 26,000 of all 36,000 Confederate POWs retained in Ohio military prisons. Crowded and unhealthy living conditions at Camp Chase took a heavy toll among prisoners. Despite newly constructed barracks in 1864, which raised the prison capacity to 8,000 men, the facility was soon operating well over capacity. Rations for prisoners were reduced in retaliation against alleged mistreatment at Southern POW camps. Many prisoners suffered from malnutrition and died from smallpox, typhoid fever or pneumonia. Others, even those who received meager clothing provisions, suffered from severe exposure during the especially cold winter of 1865. In all, 2,229 soldiers died at Camp Chase by July 5, 1865, when it officially closed.

Original Physical Appearance: The flat, farming land that became Camp Chase was leased to the U.S. Government at the beginning of the Civil War. One hundred sixty houses were built on the site to replace the overflowing barracks at Camp Jackson on the north side of Columbus. When the first prisoners of war arrived, a stockade was built on the southeast corner of the campgrounds. This stockade rested on a half-acre plot and accommodated 450 prisoners in three single-story frame buildings with partitioned rooms and tiered bunks. Two of the buildings measured 100' x 15', and a third measured 70' x 20'. A 12' high plank wall with flanking towers surrounded the stockade, named Prison No. 1. More buildings were added in November 1861 to relieve the critical housing shortage caused by incoming prisoners. Three more 100' x 15' barracks, designated Prison No. 2, were erected on land contiguous to the fist stockade.

As more POWs filled the campgrounds, additional barracks were needed. Prison No. 3, a three-acre tract, was built in March 1862. Huts arranged in clusters of six formed a residential nucleus. Each hut measured 20' x 14'and was made of planks and a light wood frame. The huts were spaced 2 ½ feet apart in each cluster, while series of clusters formed four parallel lines separated by narrow dirt roads. In summer 1864, the huts of Prison No. 3 were demolished to make way for 17 new barracks, each 100' x 22', to accommodate 198 prisoners. Volunteer prison labor built the barracks using lumber from the previously demolished huts.

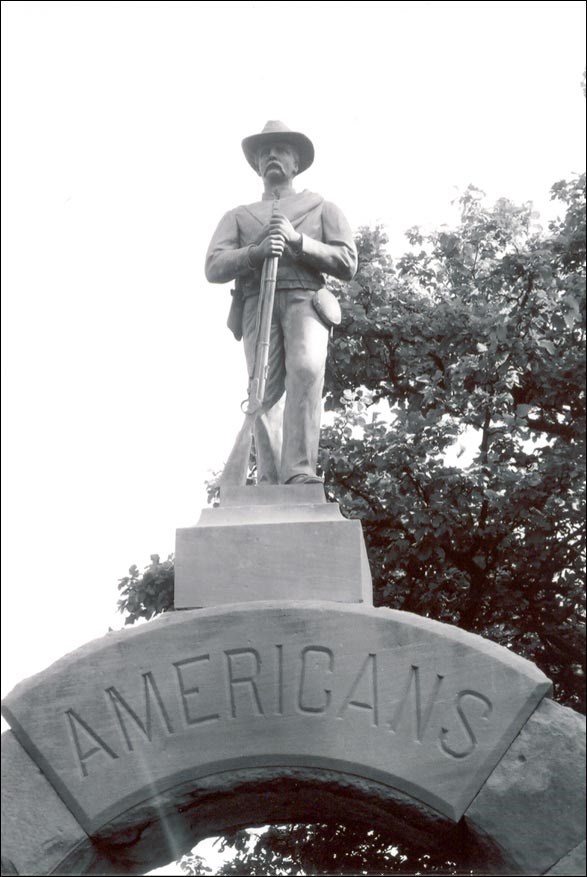

Present Physical Appearance: None of the original Camp Chase (above ground) structures exist today. All were dismantled at the end of the Civil War and the materials were reused. A prison cemetery, established in 1863, occupies less than two acres of the original campgrounds. A stone wall, built in 1921, encloses 2,199 graves of Confederate soldiers who died while POWs. To commemorate these losses, a memorial arch built of granite blocks was unveiled in 1902; it spans a large boulder just 75' inside the Sullivant Avenue entrance to the cemetery. Above the arch rests a bronze statue of a Confederate soldier facing south; the keystone of the arch is inscribed "AMERICANS." Marble headstones, authorized by an Act of Congress in 1906, identify the grave of each soldier. A stone speaker' platform, completed in 1921, stands directly behind the memorial arch along the north wall.

Questions for Reading 1

1. What purpose was Camp Chase meant to serve when it was first built? How did its use change over time?

2. Give an example of a type of political prisoner held at Camp Chase? Why do you think it might have been important to hold these people prisoner?

3. How did African Americans become imprisoned at Camp Chase? Why were Columbus citizens outraged by this?

4. Why did the population of Camp Chase swell after 1863? What problems did this cause?

5. What remains of Camp Chase prison today?

¹ 45th Congress, Session 3, from December 2, 1878 to March 3, 1879 (17 Stat., 545, ch. 229).

² Excerpt from Phillip R. Shriver and Donald J. Breen, Ohio's Military Prisons in the Civil War for the Ohio Historical Society (Columbus, OH: Ohio State University Press, 1964) 12-14.

Determining the Facts

Reading 2: Confederate POW Burials

Camp Chase cemetery had a key role in the development of the federal government's policy on marking Confederate graves. Immediately following the war, Ohio governors took notice of the poor condition of the cemetery. In 1879, the federal government took over the title to the cemetery;¹ however, the care of the cemetery continued to be poor. Ohio governors through the 1870s and 1880s continued to champion for proper care and attention for the cemetery, which sits less than six miles from the Ohio Statehouse.

When several of Ohio's politicians became involved in national politics, they continued to pursue the Camp Chase cemetery cause. Presidents William McKinley and Rutherford B. Hayes, and U.S. Senator Joseph B. Foraker all lobbied for proper care and marking of Confederate graves located in northern cemeteries.

1. Correspondence relative to "Confederate Prisoners of War," buried in the vicinity of the late Military Prisons in the State of Ohio:

To His Excellency Jacob D. Cox, Governor of Ohio:

SIR: I have the honor to inform you that I have attended to your instructions, directing me to procure, as an appendix to lists of the Union dead, lists of the Confederate prisoners of war buried in the State.

You will find the lists in the accompanying "Book of the Confederate Dead," with plats of the several cemeteries, showing the location of each grave--the numbers of the graves corresponding to the numbers in the lists.

There are 2,307 Confederate officers and soldiers buried in the State. Of these, 1,977 are buried in the Confederate cemetery at Camp Chase, near Columbus--93 in the city cemetery, southeast of Columbus--31 in the soldiers' cemetery at Camp Dennison, and 206 in the Confederate cemetery at Johnson's Island, near Sandusky.

A substantial board fence surrounds the cemetery at Camp Chase and the graves are well protected. Head-boards have been placed at the graves, properly inscribed, with numbers upon them corresponding to the numbers in the lists… …Many of the headboards in the Confederate cemeteries in the State are now in process of decay. I presume the U.S. Government will make some provision with reference to these cemeteries, for protection, renewal of headboards, &c. If not, I would recommend that it be done by the State. It is a simple matter of humanity.

Very respectfully, your obedient servant,

D. W. TOLFORD

Ohio State Soldier's Home

Columbus, O., Dec. 12, 1866.²

2. Excerpt from the annual message of the Governor of Ohio to the 67th General Assembly, January 4, 1887.

The confederate cemetery near Columbus.... The title to it is in the United States, and that Government should care for these graves; but it seems to have overlooked them. The fence that encloses the lot is in a dilapidated condition, and the entire burial place is overgrown with weeds and thistles and briars. It is recommended that unless the United States Government can be induced to do so, an appropriation be made to rebuild the fence and clean up the grounds and put them in orderly repair and condition.

The same should be done for the last resting place of about 200 Confederate dead who are buried on Johnson's Island. The hatred and detestation that all loyal people must and should ever entertain for the destructive political doctrines that these men fought for ought not to stand in the way of either a cordial feeling toward the living who have abandoned such heresies, or a proper regard and Christian respect for the graves of the dead who, although wrong, yet heroically and valorously contended for the convictions they entertained...³

3. In his autobiography, Notes of a Busy Life (1916), Senator Foraker states:

MARKING GRAVES OF CONFEDERATES.

…While I was Governor, I recommended in my Message to the General assembly of Ohio that provisions be made for the proper care of the graves of Confederate soldiers buried at Camp Chase, near Columbus, and on Johnson's Island, in Lake Erie, near Sandusky, and how, in pursuance of my recommendation, suitable provision therefore was made.

It was probably this fact that prompted the respective organizations of ex-Confederate soldiers to request me to introduce a bill in the 57th Congress making an appropriation to pay for suitably marking graves of Confederate soldiers who had died in Northern prisons and hospitals during the Civil War and who had not been buried at the places where they died. The bill was referred to the Committee on Military Affairs and there favorably considered. I made an extended report January 22, 1903, Number 2589, 57th Congress, Second Session, showing the number of graves to be marked, where located probable cost, etc. The bill did not pass in that Congress, but I re-introduced it in the 58th Congress, where it again failed, and then re-introduced it in the 59th Congress, which finally passed it….4

The 59th Congress passed Public Law 38 approved March 9, 1906. This bill states: "An Act to provide for the appropriate marking of the graves of the soldiers and sailors of the Confederate army and navy who died in Northern prisons and were buried near the prisons where they died, and for other purposes."

Questions for Reading 2

1. During the war and immediately afterwards, the families of Confederate soldiers tried to recover the remains of lost troops. Why do you think the creation of the "Book of Confederate Dead" may have been important to relatives of those who fought in the war?

2. Why do you think Tolford stated that marking and caring for the Confederate graves is "a simple matter of humanity?"

3. How did Governor Foraker describe the condition of the cemetery? Why does he make this appeal even though he knew these soldiers were fighting against the Union and for something in which he did not believe?

4. Why do you think it took over 40 years for the U.S. Congress to provide grave markers for Confederate soldiers that died in Union prisons?

5. Why do you think ex-Confederate soldiers requested that Foraker introduce a bill for suitable grave markers instead of a politician from a southern state?

6. How did Governor Foraker's experience with Camp Chase shape his views in the U.S. Senate on the issue of Confederate POW graves?

¹Executive Documents: Annual Reports for 1886 67th General Assembly of the State of Ohio Part II, (Columbus, Oh: The Westbote Company, State Printers Columbus, 1887), 485.

² Excerpt from a report prepared by D.W. Tolford for Ohio Governor Jacob D. Cox, Columbus, Ohio, December 12, 1866. Report relative to Confederate Prisoners of War buried in the vicinity of the late military prison in the state of Ohio.

³ Excerpt from Joseph B. Foraker's autobiography Notes of a Busy Life, Volume II (Cincinnati, OH: Stewart and Kidd Company, 1916), 407.

Determining the Facts

Reading 3: Our Dead Honored

Several decades after the Civil War, many different groups--relatives of former POWs, Confederate veteran organizations, Southern women's groups, as well as Columbus residents and Union veterans--took an active interest in Camp Chase Confederate cemetery. Governor Foraker of Ohio helped secure U.S. government funds to erect a stone wall around the cemetery and procure a 16-ton boulder, which would serve as the first monument in the cemetery in the late 1880's. On the boulder was carved: "2,260 confederate soldiers of the war 1861-1865 buried in this enclosure." In 1895 a Union veteran living in Columbus, Colonel W. H. Knauss, took an interest in the cemetery and its care. On his own he organized yearly services at the cemetery. He also led a fund raising campaign that helped erect a statue of a soldier standing on a stone arch with the word "Americans" engraved on it in 1902. President McKinley, who first passed through Camp Chase as a Union soldier on his way to war and later followed the cemetery's plight as Governor of Ohio, would campaign for the care of Confederate graves until his assassination in 1901.

Confederate Veteran magazine, July 1902

"OUR DEAD HONORED IN OHIO."

CONFEDERATE MONUMENT DONATED AND DEDICATED BY OUR FORMER FOES.

The single word "Americans" is chiseled in a stone arch unveiled at the Confederate burial ground at Camp Chase Saturday afternoon. It has been built to honor the memory of Confederate dead, but all factional feeling has been hidden from sight in the simple inscription it bears. The fact that it stands among graves of only those who followed the Stars and Bars will be the evidence of its character. Its donor fought neither with the blue nor the gray. A spirit of sentiment actuated its giving.

The unveiling of the arch was made the feature of the annual custom of decorating the graves of the 2,260 dead that are buried in the little plot of ground. Six years ago this ceremony was conceived and inaugurated by Col. W. H. Knauss. The first ceremony was of an exceedingly simple character. With each succeeding year it has been made more pretentious, culminating with the unveiling of the monument to day….

One of the wisest acts, certainly the most magnanimous act of President McKinley was his advocacy of a plan for the national government to maintain the Confederate cemeteries at its expense. It was only a reiteration of what he had said twenty years before at Oberlin, Ohio. In a memorial address there, speaking of the duty of the people of Ohio with respect to the graves of the dead Confederates in Camp Chase, he said: "On us, too, rests the responsibilities of caring for their graves. If it was worthwhile to bury each man in a separate grave, or give him and honorable interment, is it not worthwhile to preserve the grave as a sacred trust, as it is, and as it is to us alone? … The line of action for us is fortunately simple. In the office of the Adjutant General of the State is a record of all these dead, with a diagram of the grounds, each grave being numbered. From this it is possible to find the grave of each man and to arrange the grounds in proper manner. Let this be done by the State. Let the Legislature provide for the oversight and care of these graves."

President McKinley made two extended tours through the Southern States. The ex Confederates, by the thousands, attended his meetings and receptions and cheered and applauded him. Nowhere in the South did anarchists assail him. His life was safer than in the North. When it became necessary to make additional major and brigadier generals for the Spanish war, this broad minded President did not hesitate to put the stars upon the shoulders of those old graybacks Generals Wheeler, Lee, Butler, Oates, and Rossiter. When McKinley died, not the North alone, but the North and the South, the whole nation, reborn, reunited, mourned his death and shed tears over his grave. The "Kindly Light" of his magnanimous example and teaching encourages and cheers us on to day in paying tribute to the heroic Confederate dead who sleep in this Confederate cemetery.

Questions for Reading 3

1. What was the first monument at Camp Chase? Why do you think it was an important gesture to add the arch with the simple inscription, "Americans?"

2. What president advocated that the U.S. government maintain Confederate cemeteries? When did he begin this campaign?

3. What is the general tone of this piece? What might the tone have been like if it were written in 1866 right after the Civil War instead of 1902?

Visual Evidence

Photo 1: Camp Chase Confederate grave.

(Photo by Paul LaRue)

Among Camp Chase's first prisoners of war were political prisoners. These political prisoners were primarily judges, mayors, and legislators from Kentucky and Virginia. When these political prisoners died there, burial records listed their name and the word "citizen." The Camp Chase cemetery is dotted with headstones bearing the word "citizen."

Questions for Photo 1

1. What do you think the word "citizen" signifies?

2. Do you think that military and civilian prisoners would be housed in the same facility today?

3. George Burgess is listed as a citizen of Ohio. What might he have done to end up at Camp Chase? If needed, refer to Reading 1.

Visual Evidence

Photo 2: Camp Chase Confederate Cemetery.

Photo 3: Camp Chase Confederate Cemetery.

(Photo by Paul LaRue)

In 1901, for the first time a number of re-interred Confederate remains, as well as several existing graves, at Arlington National Cemetery, Virginia, were marked with the permanent headstones:

These stones are 4 inches thick, plane face and angular top, and are of the pattern of the headstone adopted by the United Confederate Veterans Association to mark the graves of Confederate dead. It was the wish of this Association in selecting a standard headstone, to select one of distinctive design, and the 4 inch stone with angular top and plane face was considered to fulfill this requirement - easily distinguished from the Union headstones or others of various designs.¹

"The Arlington Confederate specifications required 36 inches long and 10 inches wide," but the Army specified a dimension of "39 inches long and 12 inches wide is better…." However, while the 1906 Act passed by Congress required the stones to be similar to those in Arlington, it did not specify "identical," and the name inscribed could be cut in a curve."²

Questions for Photos 2 and 3

1. What information is provided on each headstone? Do the Camp Chase headstones follow the guidelines provided by the 1906 Act? How?

2. The soldiers in Photo 2 died in December 1863 and the soldiers in Photo 3 died in January 1865. Why do you think the markers are closer together in Photo 3?

3. Why do you think it was so important to provide proper recognition to these fallen soldiers?

¹ "Old Headstones" report, author and date (c. 1910) unknown, Commission for Locating and Marking Confederate Graves, RG 92, Box 6. Folder R#8 (1) NARA

² Letter from Commissioner Elliott to Depot Quartermaster in Boston, March 23, 1907. Commission for Locating and Marking Confederate Graves, RG 92, Box 2, Folder D#1, NARA

Visual Evidence

Photo 4: Camp Chase Confederate Memorial.

Photo 5: Camp Chase Confederate Memorial.

Questions for Photos 4 and 5

1. What was the original monument at Camp Chase? When was it placed there? (If needed, refer to Reading 3.)

2. When was the second monument added? Why do you think it was added? (If needed, refer to Reading 3.)

3. Which direction is the soldier on the monument facing? (If needed, refer to Reading 1.) Why is the direction significant?

Putting It All Together

In this lesson, students learn about the history of Camp Chase and the federal government's policies guiding the marking of POW graves. The following activities will help them apply what they have learned.

Activity 1: Research a Prisoner of War Camp

Have students research and compile a list of some of the larger Civil War prisoner-of-war camps. Divide students into teams assigning each group a camp on which to research and report. Make sure the class is evenly divided representing both Southern and Northern camps. Some questions to consider: Where was the camp located and why was it built there? What was life like for camp prisoners? What was the mortality rate? What happened to the camp after the war? Are the structures still in existence today? Did the camp become a cemetery for those who died there? Is the camp a park (national, state, or local) and is it interpreted as a historic site? If so, contact the site and request further information. Have students report their finding and then hold a class discussion on how their camps compare to what they have learned about Camp Chase.

Activity 2: National Cemetery System

Camp Chase Confederate Cemetery is one of 33 small soldiers' lots and Confederate cemeteries maintained by the National Cemetery Administration (NCA), Department of Veterans Affairs. In 1862, President Abraham Lincoln signed legislation that created the National Cemetery system and 14 national cemeteries. Ten years later, another 62 were established. The U.S. government, facing an unprecedented situation with the number of casualties during this war, realized that it had to devise a system to honor and care for these lost soldiers. Have students research the development of the National Cemetery System and write a paper on their findings. Be sure students include when Confederate burials became part of this story. Also make sure that students include in their research the role of that the NCA plays today in honoring veteran soldiers. (Have students visit the Department of Veteran Affairs National Cemetery Administration website to begin their research.)

Not to Be Forgotten: Camp Chase Confederate Cemetery--

Supplementary Resources

By studying Not to Be Forgotten: Camp Chase Confederate Cemetery students learn about the history of Camp Chase and the federal government's policies guiding the marking of POW graves. Those interested in learning more will find that the Internet offers a variety of interesting materials.

Library of Congress

Search the American Memory Collection for a variety of primary sources related to Civil War prisoner-of-war camps including diary entries, sketches, maps, pictures, and much more.

Department of Veterans Affairs: National Cemetery Administration

For more information about the National Cemetery Administration and its history, soldier's lots, and the federal government's grave marking program, please visit the NCA website.

United States War Department: The War of Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies

This Cornell University database contains a massive amount of primary source data of both the Union and Confederate armies including: correspondence, official reports, orders, information on prisoners of war, state prisoners, political prisoners, and the reports of high ranking military officials.

Further Reading:

Students interested in learning more may want to read Margaret E. Wagner, Gary W. Gallagher, and Paul Finkelman's The Library of Congress Civil War Desk Reference (New York: Simon and Schuster Publishing, 2002).