During the 1960s, Peter Hurd, a famed artist of the Southwest, painted the watercolor Elephant Butte Lake, capturing southern New Mexico’s Elephant Butte land formation rising from the reservoir’s placid waters, where, at sunset, boats rest upon the bluff’s reflection. Painted as part of a campaign to enhance the Bureau of Reclamation’s public image, the reservoir that was Hurd’s muse is part of Reclamation’s Rio Grande irrigation project. Since their completion in 1916, the Elephant Butte Dam and Reservoir on the Rio Grande, 125 miles north of El Paso, Texas, has supplied the arid river valley with reliable irrigation water. Local people, however, soon found other uses for the desert lake, which eventually became the “most utilized outdoor recreation area in New Mexico,” hosting upwards of one million visitors annually. The Bureau of Reclamation found yet another use for the lake’s 2.2 million acre feet of water — power development. Like recreation, generating electricity for non-irrigation use wasn’t originally part of the Rio Grande Project – but since 1940, the Elephant Butte Powerplant has been generating electricity to serve the local area and beyond.

Initial development at Elephant Butte began for two reasons: to provide farmers along the Rio Grande in Texas with a reliable irrigation water supply, and to fulfill the terms of a 1906 treaty between the United States and Mexico on the distribution of the waters of the Rio Grande. Elephant Butte Dam was one of the first engineering structures built to settle an international dispute (see the Elephant Butte Dam site description to understand why there was a water dispute with Mexico). In 1910, dam construction kicked off with the building of a work camp and a 10.5-mile rail line to connect the dam site with the Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe Railway at Engle, New Mexico. With the final spike driven early in 1911, the new railroad brought coal to fuel a small electric plant at the site, needed for dam construction. A tiny 150-kilowatt hydroelectric plant was completed at the dam in 1915 to power construction. Although six gated penstock openings were built into the dam for future, expanded hydroelectric development, maintaining water storage for irrigation held priority, and full power development was delayed for the time being. (It was common practice for Reclamation to build future hydroelectric capability into dams, even where no powerplants were initially constructed.)

In 1925, catastrophic summer floods swept the Rio Grande Valley, causing project farmers to ask Reclamation to build a second dam for flood control. Around the same time, there was increasing demand in the valley for electricity, as more farmers settled on the Rio Grande Project. Reclamation agreed that a flood control dam was needed to protect the project’s diversion dams and canal headworks from damage. Reclamation also recognized that a flood control dam positioned downstream of Elephant Butte could recapture water released from Elephant Butte Dam – opening up the possibility for a hydroelectric powerplant at Elephant Butte Dam. (At that time, Reclamation was allowed to release water only for irrigation purposes and not solely for hydroelectric purposes – so a second dam that could recapture non-irrigation water releases from an upstream powerplant was essential.)

But, in the 1920s, there was little support for the Federal Government getting into the “power business” in competition with private industry. It wasn’t until the 1930s, during the Great Depression, that the Elephant Butte Powerplant project was able to move forward with funding from the Public Works Administration (PWA). New Deal programs were a significant, sometimes the primary, source of funding for Reclamation projects during the Great Depression. Construction of the Elephant Butte Powerplant would not only create jobs, but because it was funded by PWA, the water users would not have to repay the construction cost to the Federal Government, which was normally a standard requirement for Reclamation projects. The PWA contracts for Elephant Butte Powerplant released the water users associations from reimbursement because construction would be repaid solely from net power revenues.

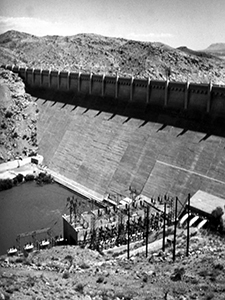

Construction of the downstream flood control dam that project farmers requested – the Caballo Dam – began in 1935. Caballo Dam was completed in 1938, the same year that work began on the new, much larger, powerplant at the toe of Elephant Butte Dam, using the penstocks constructed through the dam in 1916. There, workers installed three 8,100 kilowatt generators, replacing the small 150 kilowatt plant that had been in service since 1915. Water released from Elephant Butte Dam for winter-time power generation was recaptured 25 miles downstream at Caballo Dam, allowing year-round power generation at Elephant Butte Powerplant. Upon completion in 1940, the Elephant Butte Powerplant was New Mexico’s first large-scale hydroelectric power station.

The electricity generated at the new plant was immediately put to use at the reservoir to enhance the lake’s newly constructed recreational facilities. State and Federal-funded highways had reached the remote lake in the 1920s, and area residents and vacationers flocked to its shores to fish, camp, and go boating. Then, in the 1930s, Reclamation was able to utilize another New Deal program, the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), to enhance the recreational experience at the reservoir. The CCC built hiking trails, lakeside tourist cabins in the Pueblo Revival style, a boat house, and campgrounds that were even equipped with electrical outlets for trailers and appliances. In 1939, nearly 5,000 recreationists attended the “Ninth Annual Regatta,” which featured hydroplane, motorboat, and swimming competitions. Thrill-seekers paid the 50-cent fare for a speedboat ride, while others relaxed onshore, casting out their lines, hoping to lure fish supplied by hatcheries built by CCC crews.

Reclamation first transmitted hydroelectricity beyond the dam and reservoir site in 1940, the year construction wrapped. A 62-mile-long transmission line served farms of the Rio Grande Project and homes in Hot Springs (now Truth or Consequences) and Las Cruces, New Mexico. The next year, Reclamation extended its distribution network to Deming and Central. Ultimately, Reclamation constructed a 490-mile transmission system, with half of the power going to New Mexico, the other half to Texas. Reclamation managed Elephant Butte Powerplant operations until 1977, when the distribution system was sold to a private electric company that administers transmission to Nebraska, Wyoming, Colorado, and New Mexico, while Western Area Power Administration (WAPA), a division of the Department of Energy, markets the power.

The Elephant Butte Historic District, listed on the National Register of Historic Places, incorporates Elephant Butte Dam, Elephant Butte Powerplant, the original Reclamation Service office building, as well as an array of surrounding buildings, structures, and archeological sites that directly relate to the construction and subsequent operation of the dam and reservoir. The historic district also includes many surviving buildings and structures that date to the New Deal-era and represent the work of the young men of the CCC, such as landscaping, roads, and a campground. In 1976, the American Society of Civil Engineers designated Elephant Butte Dam as a Historic Civil Engineering Landmark.

Visit the National Park Service Travel Bureau of Reclamation's Historic Water Projects to learn more about dams and powerplants.

Last updated: January 13, 2017