Last updated: October 26, 2020

Article

Before the Signatures: A New Vázquez de Coronado Site at the El Morro NM

NPS

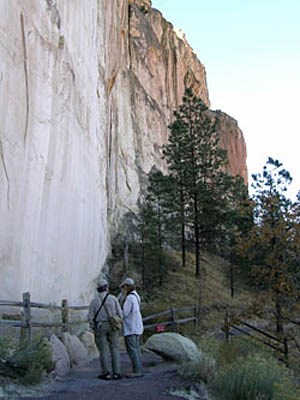

Over the last four centuries, the site of Inscription Rock – also known as El Morro National Monument – has become a signature historical monument in both a literal and figurative sense. Lying close to the Continental Divide and located along the well-traveled prehistoric route between Zuni and Ácoma Pueblos in west-central New Mexico, Inscription Rock has attracted a wide range of prehistoric and historic period occupations(1). The large concentration of rock art and engraved signatures on this imposing sandstone promontory bear witness to the frequency of these visits and activities(2), and inspired one of the site’s more popular names.

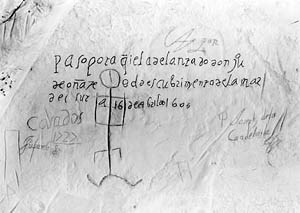

While two Ancestral Pueblo sites on the mesa top are believed to have been occupied from c. 1275 to 1350 AD(3), and Native American petroglyphs along the base of Inscription Rock range from the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries AD(4), the earliest known European inscription at the site dates to 1605(5). Don Juan de Oñate, the first Spanish Governor of New Mexico, visited the El Morro area in that year and engraved a dated memorial following the return of his expedition from the “South Sea” (i.e., the Gulf of California)(6).

During the last five hundred years, a number of important factors have made El Morro an attractive location for travelers: the excellent grazing resources in the El Morro Valley, the large pool of water or tinaja located at Inscription Rock, the shallow playa lakes that appear periodically in the immediate vicinity, the shelter afforded from bitterly cold west winds, and the site’s proximity to the well-traveled Zuni-Ácoma Trail.

NPS

Until November 2007, the earliest physical trace of a European presence at the site was the 1605 Oñate inscription. Although historical documents hint at visits by earlier sixteenth-century Spanish entradas(7) – particularly the 1583 expedition led by Antonio de Espejo(8) – no material evidence of these expeditions had ever been identified at the El Morro National Monument.

Following work directed by Charles Haecker in late 2007, and funded by the National Park Service (NPS) Heritage Partnerships Program, dramatic new evidence emerged linking El Morro with the earliest major Spanish entrada in the desert Southwest – i.e., the 1540-1542 expedition of Capitan General Francisco Vázquez de Coronado. A range of metal artifacts recovered during this two-day investigation point to the presence of the Vázquez de Coronado expedition. These artifacts include: three caret-headed nails (horse shoe nails), a lead (or copper alloy) coin or scale weight, a wrought iron needle, and a wrought iron chain which may be a bridle chain. Although a number of other Spanish Colonial objects were found in the course of this preliminary survey, such as a rose-head nail (a hand forged nail), a cast iron escutcheon plate, and two wrought iron nail shafts, none of these artifacts can be dated more precisely at this time.

NPS

Caret-headed nails are considered some of the most diagnostic artifacts associated with the expedition of Vázquez de Coronado, since they are found on a variety of other sites linked with this entrada in both New Mexico and Texas(9). Furthermore, caret-headed nails were found at the Governor Martin site, near Tallahassee, Florida – a location widely believed to be Hernando de Soto’s 1539-1540(10) winter camp. In addition, Mathers and Haecker(11) have demonstrated recently that caret-headed nails are not only known in a variety of contexts in Central-South America and Europe during the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries, but that these nail forms appear to be largely, if not altogether, absent in later sixteenth-century and early seventeenth-century contexts in many parts of North America. While further research remains to be done, these patterns appear to be widespread and may be applicable not only to the American Southwest and Southeast, but to areas further afield as well.

The scale weight or coin weight found at El Morro during our survey bears a striking resemblance to an object recovered by Kathleen Deagan at the site of Concepción de la Vega (c. 1496-1502) in the Dominican Republic. The close correspondence in appearance between these two artifacts, and their similar function, was confirmed Deagan after examining photographs of the El Morro weight (pers. comm., March 2009)(12). In addition, a small wrought iron chain with three closed links and one terminal link left open to form a hook matches some of the morphological and metrical characteristics of sixteenth-century chains found elsewhere in the Southwest and in the United Kingdom(13). Significantly, the closest parallel to the El Morro chain – with respect to manufacturing technique, size, and shape – comes from an chain recovered from the Jimmy Owens site in the Texas Panhandle, a confirmed Vázquez de Coronado campsite. The form and rather diminutive size of the chains from El Morro and Jimmy Owens strongly suggest their use as horse gear and possibly as bridle chains(14). These parallels for the scale/coin weight and wrought iron chain point to a date in the first half of the sixteenth century.

Together with the presence of caret-headed nails, these objects imply a Spanish/European presence at El Morro in the first half of the sixteenth century and strongly suggest an association with the 1540-1542 entrada of Vázquez de Coronado. Contemporary historical documents indicate that, after spending four months at the Zuni Pueblos between July and November 1540, the approximately 2800 members of the expedition moved in a number of separate parties from the Zuni area to the Tiguex (Southern Tiwa Pueblo) region, near present day Albuquerque(15). Guided by natives, and no doubt using existing trails where possible, it is widely believed that the components of the Vázquez de Coronado expedition traveling from Zuni to Tiguex followed a route that took them through the El Morro area. The next Spanish expedition to enter New Mexico and the desert Southwest, between 1581 and 1582, was a far smaller party of some 31 individuals lead by Francisco Sánchez Chamuscado and Fray Augustín Rodríguez(16). It is our belief that during the four decades or more that separate the Vázquez de Coronado entrada from later sixteenth century expeditions in the American Southwest (including Sánchez Chamuscado-Rodríguez amongst others), there were a number of detectable changes in material culture. Consequently, it is our hope that early Contact Period assemblages in the American Southwest will be examined more systematically, and that they will be compared with both contemporary and later assemblages elsewhere. Regional and inter-regional comparative work of this kind has the potential to contribute significantly to our understanding of the Early Contact Period generally.

Further investigations at the El Morro National Monument are planned to identify and evaluate encampment areas associated with the various components of the Vázquez de Coronado entrada – large and small - that may have visited the area between the summer of 1540 when they entered New Mexico, and the spring of 1542 when the expedition returned to México. In the meantime, El Morro National Monument now has additional historical significance as a site linked with one of the most dramatic and transformational moments in the history of the desert Southwest: the 1540-1542 entrada of Vázquez de Coronado.

Finally, these discoveries provide an especially compelling case for the value of historic preservation. On 8th June, 1906, President Theodore Roosevelt signed into law “An Act for the Preservation of American Antiquities”(17) and on 8th December, 1906, El Morro was proclaimed as the nation’s second national monument(18). More than a hundred years later, the importance of that decision has been amplified by the discovery of archeological materials indicating that El Morro was visited by the first major European entrada into the American Southwest. Thanks to the passage of the 1906 Antiquities Act and the legislative foresight of President Roosevelt, the U.S. Congress and other dedicated professionals, the historic significance of the El Morro National Monument has been both preserved and enhanced. The unforeseen consequences of that Act, and the efforts made to preserve and expand the El Morro National Monument through time, emphasize the value of both historic preservation and a long-term perspective in protecting our collective cultural patrimony.

By Clay Mathers, Executive Director, The Coronado Institute, Albuquerque, NM

and Charles Haecker, Archeologist, NPS – Heritage Partnerships Program, Santa Fe, NM

A version of this report was originally published in CRM: The Journal of Heritage Stewardship,Vol. 7 (1), Winter 2010.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to extend their thanks to the staff and to Kayci Cook Collins, Superintendent, El Morro and El Malpais NM, who granted permission for our survey on short notice; Christopher Adams, Gila National Forest who lent his extraordinary expertise, good humor and analytical skills; Richard Flint and Shirley Cushing Flint, Research Fellows, Center for Desert Archaeology; Douglas Scott, Dept. of Anthropology, University of Nebraska-Lincoln; and Jim Bradford, Archeology Program Director, NPS-Intermountain Region, Santa Fe, New Mexico.

Our particular thanks go to the following, who helped enormously with identifications of early European colonial artifacts: Kathleen Deagan, Florida Museum of Natural History; Steve Wernke and William Fowler, Vanderbilt University; John Connaway, Mississippi Department of Archives and History; Jeffrey Mitchem, Arkansas Archeological Survey; Jeb Card, Southern Illinois University; Nancy Marble, Floyd County, Texas, Historical Museum; William Botts and Wade Stablein, Padre Island NS; Jonathan Damp, Humboldt State University; Robin Gavin, Spanish Colonial Art Museum; Cordelia Snow, Archaeological Records Management Section; Julia Clifton, Museum of Indian Arts and Culture; Frances Levine, Museum of the Palace of the Governors; David Snow, Cross-Cultural Research Systems; and Bruce Huckell, David Phillips and Ann Ramenofsky at the University of New Mexico; Robin Boast, Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, University of Cambridge; Andrew Myers, University of Manchester; John Clark and Geoff Egan, Museum of London; and Glenn Foard, English Heritage-Battlefields Trust.

Notes

- James H. Simpson, Report and Map of the Route from Fort Smith, Arkansas to Santa Fe,New Mexico, U.S. Senate, Executive Document 12, 31st Congress, 1st Session, 1850 (Washington, D.C.: Robert Armstrong, 1850) 1-12; Captain Lorenzo Sitgreaves, Report of an Expedition Down the Zuni and the Colorado Rivers in 1851 (Chicago, IL: Rio Grande Press, 1853 [1962]); S.W. Woodhouse, “Report on the Natural History of the Country Passed Over by the Exploring Expedition Under the Command of Brevet Captain L. Sitgreaves, U.S. Topographical Engineers, During the Year 1851,”, in Captain Lorenzo Sitgreaves, Report of an Expedition Down the Zuni and Colorado Rivers in 1851, U.S. Senate, Executive Document 59, 32nd Congress, 2nd Session, 1853 (Washington, D.C.: Robert Armstrong, 1853) 35; Walter J. Fewkes, “Reconnaissance of Ruins in or Near the Zuni Reservation”, Journal of American Ethnology and Archaeology 1 (1891) 117; Adolph F. Bandelier, “Final Report of Investigations Among the Indians of the Southwestern United States, Carried On Mainly in the Years from 1880 to 1885 (Part II),” Papers of the Archaeological Institute of America, American Series 4 (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1892) 328-329; Leslie Spier, “An Outlier for a Chronology of Zuni Ruins,” Anthropological Papers of the American Museum of Natural History 18 (New York, NY: American Museum of Natural History, 1917) 248; Lewis B. Lesley, (ed.), Uncle Sam’s Camels: The Journal of May Humphreys Stacey Supplemented by the Report of Edward Fitzgerald Beale (1857-1858) (Marino, CA: Huntington Library Press, 1929 [2006]) 85; Irving A. Leonard, The Mecurio Volante of Don Carlos de Sigüenza y Góngora. An Account of the First Expedition of Don Diego de Vargas into New Mexico in 1692. Quivira Society Publications Volume III. (Los Angeles, CA: Quivira Society, 1932) 78; J Manuel Espinosa, Crusaders of the Río Grande: The Story of Don Diego de Vargas and the Reconquest and Refounding of New Mexico (Chicago, IL: Institute of Jesuit History, 1942) 92; Richard B. Woodbury, “Columbia University Archaeological Fieldwork, 1952-1953”, Southwestern Lore 19 (1954):11; Richard B. Woodbury, “The Antecedents of Zuni Culture”, Transactions of the New York Academy of Sciences, Series 2, 18 (1956):557-563; Richard Woodbury and Natalie F.S. Woodbury, “Zuni Prehistory and the El Morro National Monument”, Southwestern Lore 21 (1956):56-60; Grant Foreman, A Pathfinder in the Southwest: The Itinerary of Lieutenant A.W. Whipple During His Explorations for a Railway Route from Fort Smith to Los Angeles in the Years 1853 and 1854 (Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 1968) 132-134; Steven A. LeBlanc, “Settlement Patterns in the El Morro Valley, New Mexico,” in Robert Euler and George Gummerman (eds.),Investigations of the Southwestern Anthropological Research Group (Flagstaff, AZ: Museum of Northern Arizona, 1978) 45-52; Patty Jo Watson, Steven A. LeBlanc and Charles Redman, “Aspects of Zuni Prehistory: Preliminary Report on the Excavations and Survey in the El Morro Valley of New Mexico,” Journal of Field Archaeology 7 (1980):201-218; Keith W. Kintigh, Settlement, Subsistence, and Society in Late Zuni Prehistory,Anthropological Papers, Number 44 (Tucson, AZ: University of Arizona Press, 1985) 44-45, 80-81; Mary McDougall Gordon (ed.), Through Indian Country to California: John O. Shepburne’s Diary of the Whipple Expedition, 1853-1854. (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1988) 127-128; Steven A. LeBlanc, “Warfare and Aggregation in the El Morro Valley, New Mexico,” in Glen E. Rice and Steven A. LeBlanc (eds.), Deadly Landscapes: Case Studies in Prehistoric Southwestern Warfare (Salt Lake City, UT: University of Utah Press, 2001) 19-49.

- John M. Slater, El Morro, Inscription Rock, New Mexico. The Rock Itself, the Inscriptions Thereon, and the Travelers Who Made Them (Los Angeles, CA: The Plantin Press, 1961) 49; Polly Schaafsma, Rock Art In New Mexico (Santa Fe, NM: Museum of New Mexico, 1992) 25, 148-150.

- Richard B. Woodbury, Southwestern Lore 19 (1954):11; Richard B. Woodbury, Transactions of the New York Academy of Sciences, Series 2, 18 (1956):557-563; Richard Woodbury and Natalie F.S. Woodbury, Southwestern Lore 21 (1956):56-60.

- James E. Bradford, An Archeological History of El Morro National Monument, Report Draft on File, National Park Service Intermountain Archeology Program, Cultural Resources Professional Paper 71 (Santa Fe, NM: National Park Service, 2007).

- Marc Simmons, The Last Conquistador: Juan de Oñate and the Settling of the Far Southwest (Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 1991) 175.

- Herbert E. Bolton, “Father Escobar’s Relation of the Oñate Expedition to California,” The Catholic Historical Review, 1st Series, 5 no. 1 (1919):19-41; George P. Hammond and Agapito Rey, Don Juan de Oñate: Colonizer of New Mexico 1598-1628. Part II. Coronado Cuarentennial Publications, 1540-1940. Volume VI (Albuquerque, NM: University of New Mexico Press, 1953) 1012-1031.

- Entrada - entry into, and direct reconnaissance of, new territory by a european-led expeditionary group.

- Evidence for a visit to El Morro by the expedition of Antonio de Espejo in 1583 is compelling. The narrative account of Diego Pérez de Luxán, a member of the Espejo party, suggests it is very probable that this group did camp in the El Morro area (see George P. Hammond and Agapito Rey, Expedition into New Mexico Made by Antonio de Espejo 1582-1583 as Revealed in the Journal of Diego Pérez de Luxán, A Member of the Party (Los Angeles, CA: Quivira Society Publications. Volume I. The Quivira Society, [reprinted New York, NY: Arno Press, 1930 [1967]) 35, 88. Traveling from the Pueblo of Ácoma to the Zuni area in March of 1583, Pérez de Luxán indicates:

We set out from this place [El Elado] on the eleventh of the month and marched three leagues and stopped at a waterhole at the foot of a rock. This place we named El Estanque del Peñol. (Hammond and Rey 1930 [1967]:88)

- Bradley J. Vierra, (ed.) A Sixteenth-Century Spanish Campsite in the Tiguex Province,Laboratory of Anthropology Note 475 (Santa Fe, NM: Museum of New Mexico, 1989); Bradley J. Vierra, “A Sixteenth-Century Spanish Campsite in the Tiguex Province: An Archaeologist’s Perspective,” in Bradley J. Vierra (ed.), Current Research on the Late Prehistory and Early History of New Mexico. Special Publication 1 (Albuquerque, NM: New Mexico Archaeological Council, 1992) 165-174; Bradley J. Vierra and Stanley M. Hordes, “Let the Dust Settle: A Review of the Coronado Campsite in the Tiguex Province,” in Richard Flint and Shirley Cushing Flint (eds.), The Coronado Expedition to Tierra Nueva: The 1540-1542 Route Across the Southwest (Niwot, CO: The University Press of Colorado, 1997) 249-261; Donald J. Blakeslee, and Jay C. Blaine, “The Jimmy Owens Site: New Perspectives on the Coronado Expedition,” in Richard Flint and Shirley Cushing Flint (eds.), The Coronado Expedition from the Distance of 460 Years (Albuquerque, NM: University of New Mexico Press, 2003) 203-218; Jonathan E. Damp, The Battle of Hawikku, Archaeological Investigations of the Zuni-Coronado Encounter at Hawikku, the Ensuing Battle, and the Aftermath during the Summer of 1540. Zuni Cultural Resources Enterprise Report 884, Research Series 13 (Zuni, NM: Zuni Cultural Resources Enterprise, 2005); Clay Mathers, Phil Leckman, and Nahide Aydin, “‘Non-Ground Breaking’ Research at the Edge of Empire: Geophysical and Geospatial Approaches to Sixteenth-Century Interaction in Tiguex Province (New Mexico),” Paper Presented for the SymposiumBetween Entrada and Salida: New Mexico Perspectives on the Coronado Expedition,Charles Haecker and Clay Mathers, organizers. Society for Historical Archaeology Annual Conference, Albuquerque, New Mexico, January 12, 2008.

- Ewen, Charles, “The Archaeology of the Governor Martin Site. The Data,” in Charles R. Ewen and John H. Hann. Hernando de Soto Among the Apalachee: The Archaeology of the First Winter Encampment (Gainesville, FL: University of Press of Florida, 1998) 59-98.

- Clay Mathers and Charles Haecker, Social and Spatial Modeling of Historic Period Expeditions at El Morro National Monument (El Morro, New Mexico) (Denver, CO: National Park Service, forthcoming); Clay Mathers and Charles Haecker, “Between Cíbola and Tiguex: Modeling the Vázquez de Coronado Expedition at the El Morro National Monument,” in Richard Flint and Shirley Cushing Flint (eds.), So You Think You Know About the Coronado Expedition? (Albuquerque, NM: University of New Mexico Press, in preparation).

- Our thanks to Dr. Deagan for her help in identifying this object and its possible functions. Also, see Kathleen Deagan, Artifacts of the Spanish Colonies of Florida and the Caribbean, Volume 2: Portable Personal Possessions (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 2002) 261, Figure 12.19, object in three o’clock position.

- In addition to the chain from the Vázquez de Coronado site of Jimmy Owens in the Texas Panhandle, there are examples with similar characteristics from the wreck of the Spanish vessel San Esteban, which went down near Padre Island, Texas in April 1554 - see J. Barto Arnold, and Robert Weddle, The Nautical Archaeology of Padre Island: The Spanish Shipwrecks of 1554 (New York, NY: Academic Press, 1978) 234-235, Figure 23c. Another parallel comes from a chain attached to forked stirrup suspender (iron) derived from excavations by the Museum of London in the waterfront area of Southwark on the River Thames. The chain associated with the iron stirrup suspender from Southwark has ‘figure 8’-shaped links similar to the El Morro chain and was found in a refuse dump with ceramics dating to c. 1575-1600 – see Geoff Egan, Material Culture in London in an Age of Transition: Tudor and Stuart Period Finds c 1450 – c 1700 from Excavations at Riverside Sites in Southwark. Museum of London Monograph 19 (London, UK: Museum of London Archaeological Service, 2005) 164-165, Figure 165 – Object #854 ABO92.

- We are grateful to William Fouts at Lassen Volcanic NP, for his expertise in horse gear.

- Richard Flint and Shirley Cushing Flint, Documents of the Coronado Expedition, 1539-1542. “They Were Not Familiar with His Majesty, nor Did They Wish to Be His Subjects”,(Dallas, TX: Southern Methodist University Press, 2005) 400-402.

- George P. Hammond and Agapito Rey, The Rediscovery of New Mexico 1580-1594: The Explorations of Chamusacado, Espejo, Castaño de Sosa, Morlete and Leyva de Bonilla y Humaña. Coronado Cuarentennial Publications, 1540-1940. Volume III. (Albuquerque, NM: University of New Mexico, 1966) 8.

- David Harmon, Francis P. McManamon and Dwight T. Pitcaithley, “Introduction: The Importance of the Antiquities Act,” in David Harmon, Francis P. McManamon and Dwight T. Pitcaithley (eds.), The Antiquities Act: A Century of American Archaeology, Historic Preservation and Nature Conservation (Tucson, AZ: University of Arizona Press) 2.

- David Harmon, Francis P. McManamon and Dwight T. Pitcaithley (eds.), “Appendix: Essential Facts and Figures on the National Monuments” in David Harmon, Francis P. McManamon and Dwight T. Pitcaithley (eds.), The Antiquities Act: A Century of American Archaeology, Historic Preservation and Nature Conservation (Tucson, AZ: University of Arizona Press) 288; John M. Slater, El Morro, Inscription Rock, New Mexico. The Rock Itself, the Inscriptions Thereon, and the Travelers Who Made Them (1961) 49.