“America was, and ever has been, the country of my choice.” —Ned Myers American citizen and erstwhile British subject

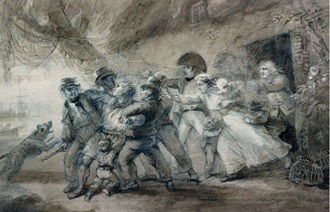

The Press Gang at work by Luke Clennell (1781-1840).

Ned Myers was born a British subject in Canada in 1793. As a child he moved to New York City, an eventually became an American sailor. In 1813, Myers was aboard an American warship on Lake Ontario that was captured by the British. Myers found himself imprisoned in Quebec; the charges revolved around his national allegiances. Myers considered himself an American, the country of his choice. In Myers’ view, he had been a British subject only by the accident of his birth. As soon as he was old enough, Myers had chosen to become an American citizen. “America was, and ever has been, the country of my choice,” Myers said, in spurning his status as a British subject. “I think I had a right to make myself what I pleased.”

His British captors did not see it that way. In their eyes, British subjects could not officially renounce their country or claim naturalized status. A British subject was a subject for life. Thus, in the British view, any subject who served with the Americans during the war was a traitor to the crown. Myers had good reason to fear for his life while in British hands.

While at Quebec, a British press gang seized Myers and some other sailors. Myers ended up in Bermuda on a merchant ship and was eventually transferred back to Halifax, where he was released from captivity in 1815. Myers spent much of his later life as a sailor, both in the American merchant sail and the navy.

Before the war, Myers had served with and befriended a midshipman named James Fenimore Cooper. In the 1840s, Myers paid a visit to Cooper at Cooperstown New York. Cooper, by that time a distinguished author, worked with Myers on his autobiography, Ned Myers; Or a Life Before the Mast.

Was Myers a subject or citizen? Myers insisted the latter, emphasizing his own power to choose his nationality. But Myers also recalled that a British naval officer who once boarded his ship told a member of the American crew “You are an Englishman, and the King has need of your services.” That two such radically different ideas about the nature of birthright coexisted in 1812 suggests that the implications of the American Revolution remained far from settled even decades after its end.

Last updated: September 14, 2017