Last updated: July 18, 2024

Article

Archeology at Brown v. Board of Education National Historical Park

Between the 1860s and 1926, the Monroe School neighborhood was an active, working-class African American community. However, the historical record of this important time prior to the Civil Rights period does not tell us much about the daily life of people in the neighborhood.

The chance to learn more came just before the 2004 opening of the new visitor’s center of the Brown v. Board of Education National Historic Site, housed in the Monroe Elementary School. Before the opening, the school building needed substantial work. The Midwest Archeological Center completed archeological projects during the school rehabilitation work between 1999 and 2003. The results of these projects tell us about how people in the earlier Monroe School neighborhood lived and related to the wider world.

The History of the Monroe School Neighborhood

Jacob Chase, one of the nine founders of Topeka, first owned the land where the Brown v. Board of Education National Historic Site is today. He sold a 160-acre plot to John and Mary Ritchie in 1855. The Ritchies first used the land as their homestead and farm. In the 1860s Ritchie began selling 75-ft by 100-ft parcels to free African Americans and others. Ritchie was a staunch supporter of the anti-slavery movement and the Underground Railroad. He helped many African Americans settle in Kansas during the Civil War period.

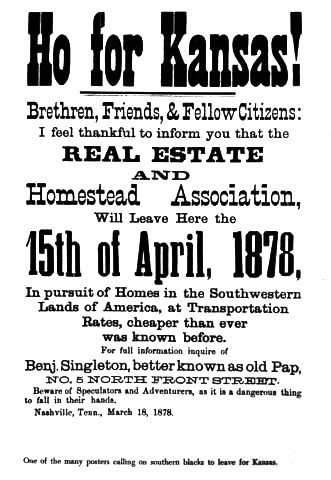

Following the Civil War, the economics of the Reconstruction Period in the South kept African Americans disenfranchised and poor. Euroamerican landowners leased farmland at high prices and collected large portions of profits. Freed African Americans would not gain equality until they became independent landowners, controlling their own destiny. African Americans slowly began migrating out of the former slave states in search of free land to the west.

Additionally, the attitudes regarding racial equality and civil rights from the Abolitionist movement had changed by the 1870s. African Americans faced many restrictions on their freedoms, even in a new land. Segregation of transportation, education, housing, and other public areas were very much a part of African American life. By the 1890s, African Americans lived in all five wards of Topeka and held a diverse array of positions in society. Because racial segregation affected all African Americans regardless of wealth or social status, African Americans in Topeka began joining together to promote social progress.

In the early 20th century, Topeka continued to grow as an urban center with a population of 50,000 in 1920. In the Monroe School neighborhood, population increases are evident from historic maps that document the construction of numerous structures on the west side of Monroe Street.

Archeology often provides information not available in historical records. Renovations necessary to convert the Monroe Elementary School into a visitor’s center threatened archeological artifacts and features. To help preserve these resources, Midwest Archeological Center staff provided onsite guidance to construction crews, documented the remains of structures that were uncovered, and collected a sample of artifacts.

To guide the archeological work, staff reconstructed the locations of 18 structures that were once located on the Monroe School property using Sanborn Fire Insurance Co. maps from 1889-1913. These detailed maps of cities were originally published to help the insurance industry assess fire risk.

Archeologists confirmed the presence of at least five of these structures, including the foundation of the original Monroe School, constructed in 1874. While it was one of the first African-American schools in the city, Monroe School was also known for its substandard conditions. Research shows that the surrounding neighborhood was probably a mixed-ethnicity, working-class community made up of single family residences with a frame or brick main house and several outbuildings.

Archeologists also monitored the installation of a new geothermal heating and cooling system for the visitor’s center across the street from the school in a playground area. Many new artifacts and features were uncovered and mapped using GPS, including a historical dump. The playground dump contained construction materials and other artifacts from the late 19th and early 20th centuries that had been deposited before the field became a playground.

The artifacts found in the Monroe School neighborhood show that mass consumerism was beginning to play a large part in people’s lives. We’ve identified 54 manufacturers and retailers from the artifacts collected in the neighborhood. These businesses represent four countries, fifteen states, and thirty-two cities. Although not the global economy we know today, the artifacts from the early Monroe School neighborhood reveal a strong connection to the eastern United States and Europe.

Conclusion

The archeology at Brown v. Board of Education National Historical Park tells the story of the Monroe School neighborhood and the growth of Topeka from the late 19th century into the 20th century. Part of this history is the migration of thousands of African Americans from a repressive system with deep roots in the past to a future they envisioned with new opportunities and freedoms. Unfortunately, the African American community in Topeka still had to face a system of racial inequality. This significant period in American history can help us understand race relations at the turn of the 20th century. Because this neighborhood was previously undocumented, the combination of archeology and history will continue to shed light on the people, race relations, and historical context that set the stage for a community to change a nation.