Importance

NPS/P. Calamari

Pacific blue mussels (Mytilus trossulus) are common and abundant in shallow nearshore marine waters. They often form dense stands of individuals, commonly called mussel beds. They are a valued food for humans. In the nearshore, they are consumed by many predators including sea otters, black oystercatchers, and several species of sea ducks and sea stars. Because of their ecological and cultural value, mussels are an important part of our nearshore monitoring in the Gulf of Alaska.

Findings

The sea otter population in Glacier Bay grew from five animals in 1993 to 8,508 in 2012. This is an average annual growth rate of 42%, which far exceeds the estimated maximum reproductive rate of increase of 24% per year for the species. Significant immigration in addition to reproduction within Glacier Bay must be occurring. Low growth rates of populations outside Glacier Bay support this conclusion. Lack of hunting pressure in the park may also contribute to the rapid population growth. (Hunting by Alaska natives is permitted outside the park, although pelts may not be sold except to other Alaska natives)

In observations of almost 6,000 foraging dives, the researchers confirmed an overall success rate of 92%. Sea otter diet consisted of 46% clam, 21% mussel, 4% crab, 15% urchin, and 14% other or unidentified prey.

Over the course of the study, researchers found significant changes in the size distribution and abundance of several preferred prey bivalve species. Diet and prey sampling data suggest that prey resources in areas of long-term occupation are being depleted, and a decrease in the growth rate of sea otters is predicted. However, there are still large areas of unoccupied habitat in Glacier Bay. The effects of recolonizing sea otters will continue to have profound and lasting implications for the structure and function of the nearshore marine community in and near Glacier Bay.

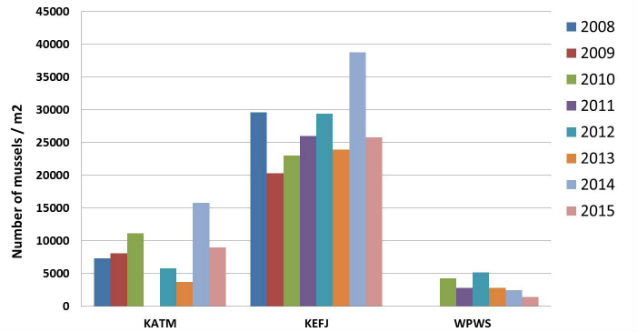

Densities of large mussels (those preferred by some predators) show the same patterns of decline and recovery as bed size. We see similar patterns of large mussel abundance across the Gulf of Alaska, with average densities declining by 50-90% and then increasing at most sites. We also monitor the abundance of small mussels to see how recruitment of juvenile mussels will eventually affect bed size. We see similar patterns of small mussel abundance across the Gulf of Alaska, with average densities at Kenai Fjords NP (about 25,000 m2) more than five times the average than in other areas (Figure 2). However, the densities of small mussels do not show the same pattern of decline and recovery observed in bed size or large mussel abundance.

Instead we see much more consistent densities of small mussels across years (Figure 2), despite the reductions of large mussels and observed bed size. It appears as though settlement of juvenile mussels occurs on a frequency and magnitude likely sufficient to support the losses of adult mussels. It also appears that survival of those recent recruits may be highly variable, possibly leading to the longer term patterns of mussel bed declines and recovery (Figure 1). Understanding how and why mussel populations vary over time will aid management and conservation of not only mussels, but also of the many consumers that rely on this important bivalve for food.

Kaflia Bay in 2008

Kaflia Bay in 2012

Kaflia Bay in 2015

For More Information

Contact: Heather Coletti, heather_coletti@nps.gov https://science.nature.nps.gov/im/units/swan/monitor/nearshore.cfm

Web article by: Erin Kunisch

Click here to print a copy of this article.

Updated April 2016

Last updated: October 26, 2021