Last updated: August 3, 2023

Article

Mount Auburn Cemetery: A New American Landscape (Teaching with Historic Places)

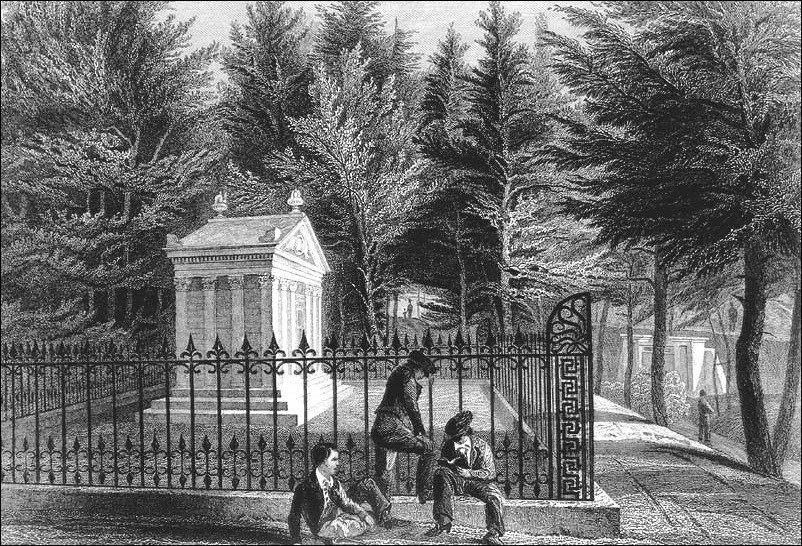

(From James Smillie's Mount Auburn Illustrated in Finely Drawn Line Engravings. Courtesy Mount Auburn Cemetery)

The situation of Mount Auburn, near Boston, is one of great natural fitness for the objects to which it has been devoted.... In a few years, when the hand of taste shall have scattered among the trees, as it has already begun to do, enduring memorials of marble and granite, a landscape of the most picturesque character will be created. No place in the environs of our city will possess stronger attractions to the visitor.... [T]he human heart...seeks consolation in rearing emblems and monuments.... This can be fitly done, not in the tumultuous and harassing din of cities,...but amidst the quiet vendure of the field, under the broad and cheerful light of heaven,....

Jacob Bigelow, 1831¹

The enduring memorials of which Jacob Bigelow so lyrically spoke were the monuments of people that would be buried in Mount Auburn Cemetery. The establishment of Mount Auburn Cemetery, about four miles outside of Boston, marked a major shift in the way Americans buried their dead. As the country's first large-scale designed landscape open to the public, it inspired many offspring--other rural cemeteries, the first public parks, and the first designed suburbs in the 19th century.

About This Lesson

This lesson plan is based on the National Register of Historic Places registration file, "Mount Auburn Cemetery" (photographs), and other documents related to the cemetery. It was produced in collaboration with the National Park Service Historic Landscape Initiative. Janet Heywood, Director of Interpretive Programs at Mount Auburn Cemetery, and Cathleen Lambert Breitkreutz, formerly Assistant Director of Interpretive Programs, wrote Mount Auburn Cemetery: A New American Landscape. Jean West, education consultant, and the Teaching with Historic Places staff edited the lesson. TwHP is sponsored, in part, by the Cultural Resources Training Initiative and Parks as Classrooms programs of the National Park Service. This lesson is one in a series that brings the important stories of historic places into classrooms across the country.

This lesson looks at cemeteries and attitudes towards death and burial. Teachers are advised to judge the emotional state and maturity level of their students before using these materials.

Where it fits into the curriculum

Topics: This lesson plan focuses on the development of new attitudes toward death, nature, and family life in the early 19th century, a time of rapidly growing urban centers and changing ideals. It can be used in U.S. history, social studies, and geography courses in units on urbanization and reform movements.

Time period: Early to mid 19th century

United States History Standards for Grades 5-12

Mount Auburn Cemetery: A New American Landscape relates to the following National Standards for History:

Era 4: Expansion and Reform (1801-1861)

-

Standard 2B- The student understands the first era of American urbanization.

-

Standard 4B- The student understands how Americans strived to reform society and create a distinct culture.

Curriculum Standards for Social Studies

National Council for the Social Studies

The lesson plan relates to the following Social Studies Standards:

-

Standard A - The student compares similarities and differences in the ways groups, societies, and cultures meet human needs and concerns.

-

Standard C - The student explains and give examples of how language, literature, the arts, architecture, other artifacts, traditions, beliefs, values, and behaviors contribute to the development and transmission of culture.

-

Standard D - The student explains why individuals and groups respond differently to their physical and social environments and/or changes to them on the basis of shared assumptions, values, and beliefs.

Theme II: Time, Continuity and Change

-

Standard C - The student identifies and describes selected historical periods and patterns of change within and across cultures, such as the rise of civilizations, the development of transportation systems, the growth and breakdown of colonial systems, and others.

-

Standard D - The student identifies and uses processes important to reconstructing and reinterpreting the past, such as using a variety of sources, providing, validating, and weighing evidence for claims, checking credibility of sources, and searching for causality.

-

Standard E - The student develops critical sensitivities such as empathy and skepticism regarding attitudes, values, and behaviors of people in different historical contexts.

-

Standard F - The student uses knowledge of facts and concepts drawn from history, along with methods of historical inquiry, to inform decision-making about and action-taking on public issues.

Theme III: People, Places and Environments

-

Standard A - The student elaborates mental maps of locales, regions, and the world that demonstrate understanding of relative location, direction, size, and shape.

-

Standard B - The student creates, interprets, uses, and distinguishes various representations of the earth, such as maps, globes, and photographs.

-

Standard D - The student estimates distance, calculate scale, and distinguish's other geographic relationships such as population density and spatial distribution patterns.

-

Standard G - The student describes how people creates places that reflect cultural values and ideals as they build neighborhoods, parks, shopping centers, and the like.

-

Standard H - The student examine, interprets, and analyze physical and cultural patterns and their interactions, such as land uses, settlement patterns, cultural transmission of customs and ideas, and ecosystem changes.

Theme IV: Individual Development and Identity

-

Standard B - The student describes personal connections to places associated with community, nation, and world.

-

Standard H - The student works independently and cooperatively to accomplish goals.

Theme V: Individuals, Groups, and Institutions

-

Standard G - The student applies knowledge of how groups and institutions work to meet individual needs and promote the common good.

Theme X: Civic Ideals and Practices

-

Standard J - The student examine strategies designed to strengthen the "common good," which consider a range of options for citizen action.

Objectives for students

1) To examine the historical causes that led to the founding of Mount Auburn Cemetery.

2) To describe the role that Mount Auburn cemetery played in early 19th-century leisure activities and the development of other rural cemeteries.

3) To analyze the landscape character of Mount Auburn Cemetery and explain how landscape qualities can affect visitors' emotions and feelings.

4) To compare the origin, design, and use of a cemetery or park in their own community with Mount Auburn Cemetery.

Materials for students

The materials listed below either can be used directly on the computer or can be printed out, photocopied, and distributed to students. The maps and images appear twice: in a smaller, low-resolution version with associated questions and alone in a larger version.

1) two maps of the site and surrounding region;

2) three readings about Mount Auburn's history and landscape design;

3) six drawings of Mount Auburn;

4) one photo of Mount Auburn.

Visiting the site

Mount Auburn Cemetery is located at the Watertown-Cambridge border, about 4 miles from downtown Boston and about one mile west of Harvard Square. The grounds are open every day of the year from 8:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m., with extended hours to 7:00 p.m. in the summer. The office is open from 8:30 a.m. to 4:30 p.m., Monday through Friday; and 8:30 a.m. to 12:30 p.m. on Saturdays. Mount Auburn remains an active cemetery and also offers a wide variety of tours and lectures throughout the year. For more information, contact the Mount Auburn Cemetery, 580 Mount Auburn Street, Cambridge, MA 02138 or visit their website.

Getting Started

Inquiry Question

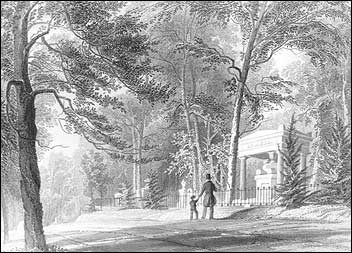

What do the people in this engraving appear to be doing?

What time period is represented?

Setting the Stage

During the first quarter of the 19th century, Boston, Massachusetts, grew from a small village into a major commercial center. Land was at a premium in the newly incorporated city, which had used up much of its original peninsula and was in the process of filling adjacent areas for expansion. Among the first priorities was the development of a safer, healthier city. Boston's burial grounds were seriously overcrowded in the rapidly expanding city; additional space was no longer available within the city limits. Residents were concerned that the burial grounds were contaminating water supplies and that gases emanating from graves threatened public health.

Attitudes about death and burial were changing significantly around this time. In Boston the burial grounds were barren landscapes—crowded, poorly maintained, devoid of plantings, and with little sense of permanence—which reinforced old Calvinist teachings about the horrors of death. As Puritanism declined, and their notions about death were replaced by gentler ideas about mortality, New Englanders began to embrace melancholy and sentimentalism as desirable states of mind.

Mount Auburn Cemetery, founded in 1831, reflected these changing notions about death and at the same time addressed the problem of overcrowded city cemeteries. Located about four miles outside of Boston, Mount Auburn Cemetery provided ample space for burials amidst a tranquil, natural setting. As the country's first large-scale designed landscape open to the public, Mount Auburn attracted not only mourners, but city dwellers wanting to experience nature, students, and tourists as well.

Locating the Site

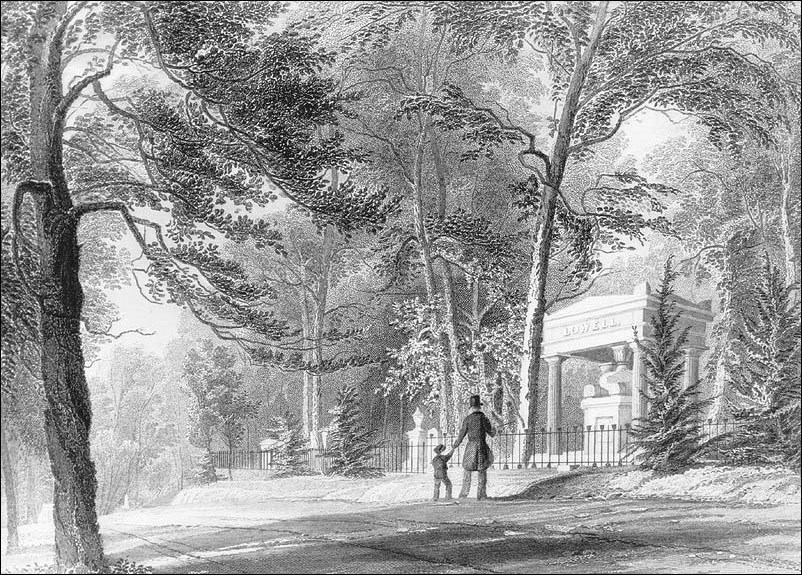

Map 1: Boston and vicinity, 1830.

(Adapted from a map published in 1830 by Abel Brown.)

Unlike earlier burial grounds in Boston, Mount Auburn Cemetery was founded in 1831 by Bostonians for their use, but it was located about four miles west of the city. It was the country's first large-scale designed landscape open to the public.

Questions for Map 1

1. Locate Boston. What limited the city's ability to expand?

2. Find the location of Mount Auburn Cemetery (denoted by a black star) on this map drawn in 1830. Why did Bostonians need a cemetery outside of the city limits?

3. From the evidence you see on the map, how is the area where the cemetery is located different from downtown Boston? How might those differences have contributed to the decision to build a cemetery in that location?

4. Since the automobile was not invented until the last decade of the 19th century, and a public horse-drawn trolley to Mount Auburn was not established until the 1840s, how might a resident of Boston have traveled to Mount Auburn in the first decade after its founding in 1831?

Locating the Site

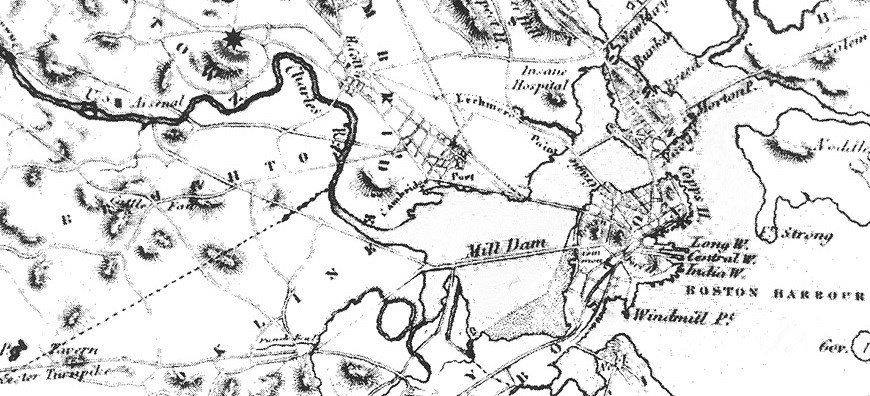

Map 2: Mount Auburn Cemetery, 1847.

(From James Smillie's Mount Auburn Illustrated in Finely Drawn Line Engravings. Courtesy of Mount Auburn Cemetery.)

The roads and paths of Mount Auburn Cemetery were laid out in a pattern designed to complement the natural, picturesque beauty of the rugged, wooded site. Early monuments were scattered widely throughout the rather dense, native forest growth, in stark contrast to the barren, flat, unplanted burying grounds of the inner city.

Questions for Map 2

1. Based on the map, what features made Mount Auburn Cemetery such a desirable place to visit? What might the shaded areas represent?

2. If you were standing on the top of the hill labeled "Mount Auburn" in the southern section of the site, what would be the shortest path to reach the Entrance at the far north edge of the site?

Determining the Facts

Reading 1: The Founding Vision--A "Garden of Graves"

Bostonians' dissatisfaction with the burial grounds of their city led the Massachusetts General Court, in 1810, to grant the town authority to regulate burials more closely. The following year, the town ordered the disinterment of many remains in old graves to reclaim space for future burials. This was not an uncommon practice in cities at that time. However, many Bostonians saw the act as a desecration of the memory of their ancestors and looked for other solutions to the problem.

The idea of a burial ground outside Boston had been discussed informally for several years, but Dr. Jacob Bigelow, a Boston physician and Harvard professor, was the first to take action. In 1825 he called a meeting of prominent Bostonians to explore the concept of a rural cemetery, a place beyond the city limits composed of burial lots interspersed with trees, shrubs, and flowers. The rural cemetery was to be a place for the living, as well as the dead, where family values and the endurance of the family would be celebrated, and nature would provide comfort and inspiration. It would be designed to be an example of the best in landscape and artistic taste.

In 1831, a committee of the newly formed Massachusetts Horticultural Society formally undertook the venture of founding the cemetery, using a 72-acre piece of property four miles west of Boston on the Watertown-Cambridge line. The Watertown family, who owned the land for decades, had cleared and farmed level areas nearby but allowed the trees of the rugged area to grow to maturity. Another attractive feature was that the topography of the land was varied; it included a network of ponds and wetlands and a mature forest of native pines, oaks, and beeches that created a place of special rural beauty. The spot was a popular retreat for Harvard College students and local residents. The students had nicknamed it "Sweet Auburn" after a town popularized in a poem by Oliver Goldsmith, "The Deserted Village." This poetic nickname inspired the name for the tallest hill at the site—Mount Auburn—and gave the cemetery its name as well.

The Mount Auburn Cemetery was formally dedicated on September 24, 1831. More than 2,000 people journeyed out from Boston on foot and by carriage to meet in a deep dell, a natural amphitheater, at the cemetery for the consecration ceremony. Joseph Story, Associate Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court, spoke at the ceremony:

A rural Cemetery seems to combine in itself all the advantages, which can be proposed to gratify human feelings, or tranquilize human fears,...And what spot can be more appropriate than this, for such a purpose? Nature seems to point it out...as the favorite retirement for the dead. There are around us all the varied features of her beauty and grandeur—the forest-crowned height;...the grassy glade; and the silent grove. Here are the lofty oak, the beech,...the rustling pine, and the drooping willow;—the tree, that sheds its pale leaves with every autumn, a fit emblem of our own transitory bloom; and the evergreen, with its perennial shoots, instructing us, that "the wintry blast of death kills not the buds of virtue".... All around us there breathes a solemn calm, as if we were in the bosom of a wilderness, broken only by the breeze as it murmurs through the tops of the forest, or by the notes of the warbler pouring forth his matin or his evening song.Ascend but a few steps, and what a change of scenery to surprise and delight us. We seem, as it were in an instant, to pass from the confines of death, to the bright and balmy regions of life. Below us flows the winding Charles [River] with its rippling current, like the stream of time hastening to the ocean of eternity. In the distance, the City,—at once the object of our admiration and our love,—rears...its lofty towers, its graceful mansions, its curling smoke, its crowded haunts of business and pleasure....

We stand, as it were, upon the borders of two worlds; and...we may gather lessons of profound wisdom by contrasting the one with the other, or indulge in the dreams of hope and ambition, or solace our hearts by melancholy meditations.

The voice of consolation will spring up in the midst of the silences of these regions of death.... The hand of friendship will delight to cherish the flowers, and the shrubs, that fringe the lowly grave, or the sculptured monument.... Spring will invite thither the footsteps of the young by its opening foliage; and Autumn detain the contemplative....

Here let us erect the memorials of our love, and our gratitude, and our glory.¹

The Boston Courier newspaper, reporting on the dedication of Mount Auburn, remarked, "[Mount Auburn] has now become holy ground and...will soon be a place of more general resort, both for ourselves and for strangers, than any other spot in the vicinity...."

Questions for Reading 1

1. Who started Mount Auburn Cemetery? When? How was its founding celebrated?

2. Where was the new cemetery located?

3. What did Joseph Story praise about the site? What do you think he meant when he said, "We stand, as it were, upon the borders of two worlds"?

Reading 1 was compiled from Jacob Bigelow, A History of the Cemetery of Mount Auburn (Boston: James Munroe and Company, 1860); Kenneth T. Jackson and Camilo J. Vergara, Silent Cities: The Evolution of the American Cemetery (New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 1989); Blanche Linden-Ward, Silent City on a Hill: Landscapes of Memory and Boston's Mount Auburn Cemetery (Columbus: Ohio State University Press, 1989); David Charles Sloane, The Last Great Necessity: Cemeteries in American History (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1991); and David Stannard, ed., Death in America (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1975).

¹ Jacob Bigelow, A History of the Cemetery of Mount Auburn (Boston: James Munroe and Co., 1860).

Determining the Facts

Reading 3: A Place for the Living--Leisure, Learning, and Mourning

Mount Auburn Cemetery became a sightseeing destination as thousands of visitors from Europe and other American cities roamed its winding paths and wrote about its attractions. Many visitors were so impressed by the beauty and many features of the place that they returned home intent on creating similar cemeteries. Within 15 years, nine major cemeteries were patterned after Mount Auburn: Laurel Hill in Philadelphia (1836); Green-Wood in Brooklyn, Mount Hope in Rochester, and Green Mount in Baltimore (1838); Albany Rural in Albany (1841); Allegheny in Pittsburgh, and Spring Grove in Cincinnati (1844); and Elmwood in Detroit and Swan Point in Providence (1846). By 1849, the Auburn model had reached the Mississippi River (Bellefontaine in St. Louis), and by 1863, the west coast (Mountain View in Oakland). Closer to home, Mount Auburn inspired the spread of rural cemeteries throughout New England in the 1840s and 1850s. The rural cemetery concept had clearly struck a chord that vibrated throughout the nation.

Mount Auburn Cemetery provided its visitors passive, educational recreation. Couples frequented the cemetery for courtship walks. Visitors were thrilled by the beauty and mystery of the landscape and intrigued by the emotional verses and images engraved on the monuments. Teachers urged youth to visit the cemetery to learn from the praise-worthy lives of heroes buried there and to gain goals for their own lives.

Many people went to Mount Auburn simply to find relief from the increasingly hectic life of the growing city. Others came as tourists, having heard that a walk through Mount Auburn Cemetery was an indispensable part of a visit to Boston. According to the American Cyclopaedia of Useful Knowledge (1835), the cemetery was "justly celebrated as the most interesting object of the kind in our country." Mount Auburn's appeal in the early 19th century was not unlike the appeal to people today of contemporary museums, public parks, amusement parks, or even malls. Numerous guidebooks provided maps, suggested tour routes and descriptions of individual monuments, and provided appropriate contemplative and spiritual readings. As early as 1845, an omnibus provided direct access from Boston. In 1847, the Fitchburg Railroad established a station at Mount Auburn; after 1856, the street railway stopped at the front gate.

Observers both famous and obscure recorded their impressions after visiting Mount Auburn Cemetery. In 1831, Lydia Maria Francis Child wrote in The Mother's Book, "So important do I consider cheerful associations with death, that I wish to see our grave-yards laid out with walks and trees, and beautiful shrubs, as places of public promenade. We ought not to draw such a line of separation between those who are living in this world, and those who are alive in another." Harriet Martineau enthused in her multivolume Retrospect of Western Travel in 1838, "I believe it is allowed that Mount Auburn is the most beautiful cemetery in the world."

A letter written by then 16-year-old Emily Dickinson to a schoolfriend on September 8, 1846, captures the future poet's impression of Mount Auburn:

...Have you ever been to Mount Auburn? It seems as if Nature had formed the spot with a distinct idea in view of its being a resting place for her children, where wearied & disappointed they might stretch themselves beneath the spreading cypress & close their eyes "calmly as to a nights repose or flowers at set of sun."¹

As Mount Auburn Cemetery continued to mature, Andrew Jackson Downing mused about its impact on the country and the potential for recreation parks in The Horticulturist and Journal of Rural Art and Rural Taste of July 1849:

One of the most remarkable illustrations of the popular taste, in this country, is to be found in the rise and progress of our rural cemeteries. Twenty years ago, nothing better than a common grave-yard, filled with high grass, and a chance sprinkling of weeds and thistles, was to be found in the Union.... Eighteen years ago, Mount Auburn, about six miles from Boston, was made a rural cemetery. It was then a charming natural site, finely varied in surface, containing about 80 acres of land, and admirably clothed by groups and masses of native forest trees. It was tastefully laid out, monuments were built, and whole highly embellished. No sooner was attention generally roused to the charms of this place than the idea of rural cemeteries took the public mind by storm.... Not twenty years have passed since that time; and, at the present moment, there is scarcely a city of note in the whole country that has not its rural cemetery.... If the road to Mount Auburn is now lined with coaches, continually carrying the inhabitants of Boston by thousands and tens of thousands, is it not likely that such a garden, full of the most varied instruction, amusement, and recreation, would be ten times more visited?²

Questions for Reading 3

1. Where were other cemeteries modeled after Mount Auburn started in the 1800s?

2. Name some of the visitors to Mount Auburn Cemetery? Why did they visit?

3. According to Andrew Jackson Downing, what impact did Mount Auburn Cemetery have on the country?

4. Where do you go to spend your leisure time? Do you look for the same things as 19th-century visitors to Mount Auburn?

Reading 3 was compiled from Karen Halttune, Confidence Men and Painted Women: A Study of Middle-Class Culture in America, 1830-1870 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1982); Blanche Linden-Ward, "Strange but Genteel Pleasure Grounds: Tourist and Leisure Uses of Nineteenth-Century Rural Cemeteries," In Cemeteries and Gravemarkers: Voices of American Culture, edited by Richard E. Meyer (Ann Arbor: U.M.I. Research Press, 1989); David Schuyler, The New Urban Landscape: The Redefinition of City Form in Nineteenth-Century America (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1986); John F. Sears, Sacred Places: American Tourist Attractions in the Nineteenth Century (New York: Oxford University Press, 1989); and Cynthia Zaitzevsky, Frederick Law Olmsted and the Boston Park System (Cambridge, Mass.: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1982).

¹Letter from Emily Dickinson to a schoolfriend, September 8, 1846, Thomas H. Johnson, ed., Emily Dickinson Selected Letters (Cambridge, Mass.: The Belknap Press, 1971), 7-8.

²Andrew Jackson Downing, The Horticulturist and Journal of Rural Art and Rural Taste, vol. 4, no. 1, July 1849.

Visual Evidence

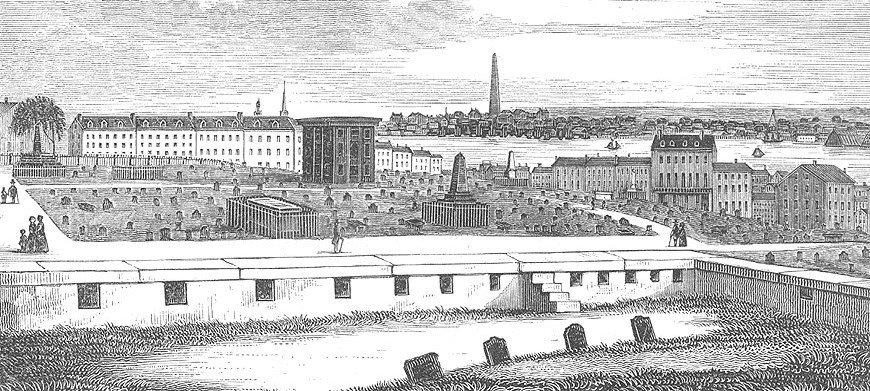

Drawing 1: Engraved view of Copp's Hill,

Boston, 1851.

As early as the 1730s, Boston's three original burial grounds--Copp's Hill, King's Chapel, and the Old Granary--became so crowded that new burials were often made four-deep or in small, common trenches. Parts of old coffins and bones sometimes were unearthed when new burials were made in common or family tombs.¹

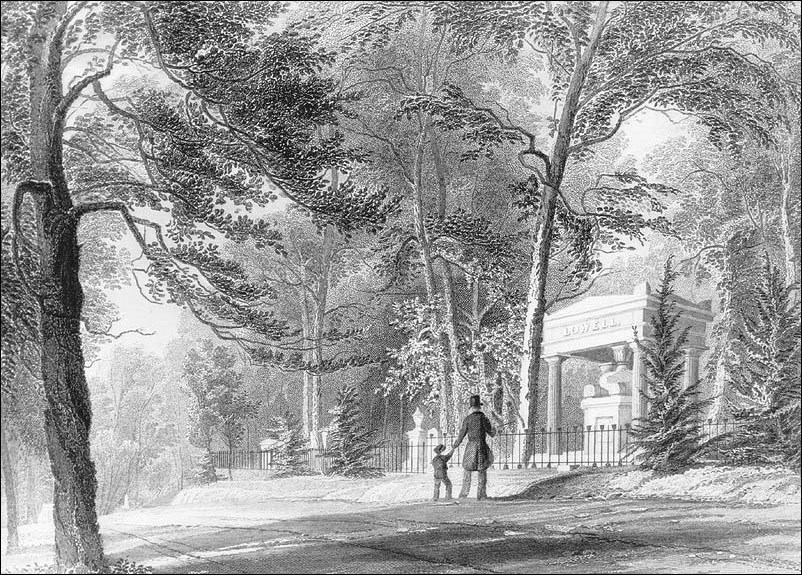

Drawing 2: Engraved view of Lowell Lot, Mount Auburn Cemetery, 1847.

Questions for Drawings 1 & 2

1. Compare Drawings 1 and 2. What is the same? What is different? What words would you use to describe each of the engravings?

2. What do you think the people in Drawing 2 are doing?

3. Imagine you were the older person depicted in Drawing 2, the 1847 engraving. What do you think you would have been saying to your young companion?

¹Blanche Linden-Ward, Silent City on a Hill: Landscape of Memory and Boston's Mount Auburn Cemetery (Columbus: Ohio State University Press, 1989), 150.

Visual Evidence

Drawing 3: Engraved view of Stow Gardens, England, circa 1760.

Drawing 3 depicts a typical English picturesque landscape.

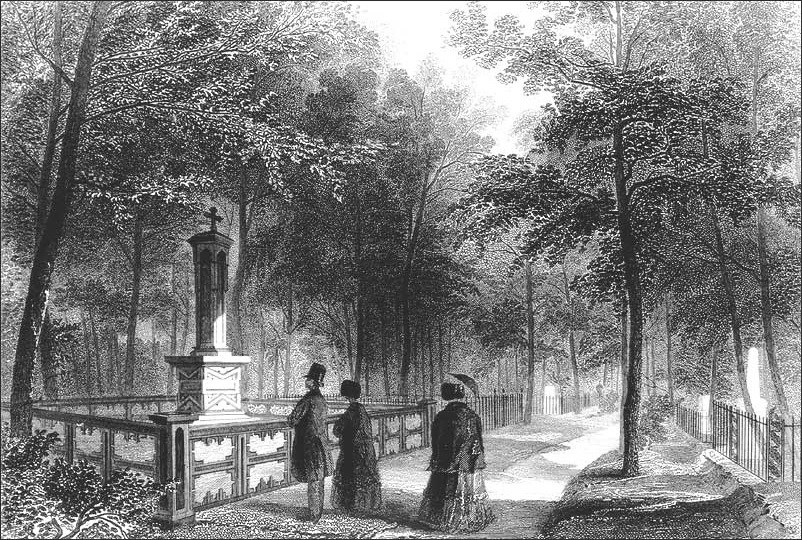

Drawing 4: Engraved view of Gossler Lot, Mount Auburn Cemetery, 1847.

Questions for Drawings 3 & 4

1. Study Drawing 3 and Drawing 4. Do you think the landscape of the new cemetery (Drawing 4) successfully captured the same feelings that the English landscape (Drawing 3) embodied? Explain your answer.

2. Which do you feel are more prominent in Drawing 4, the trees or the tombs? Why would the designers of Mount Auburn Cemetery have wanted this to be the case?

Visual Evidence

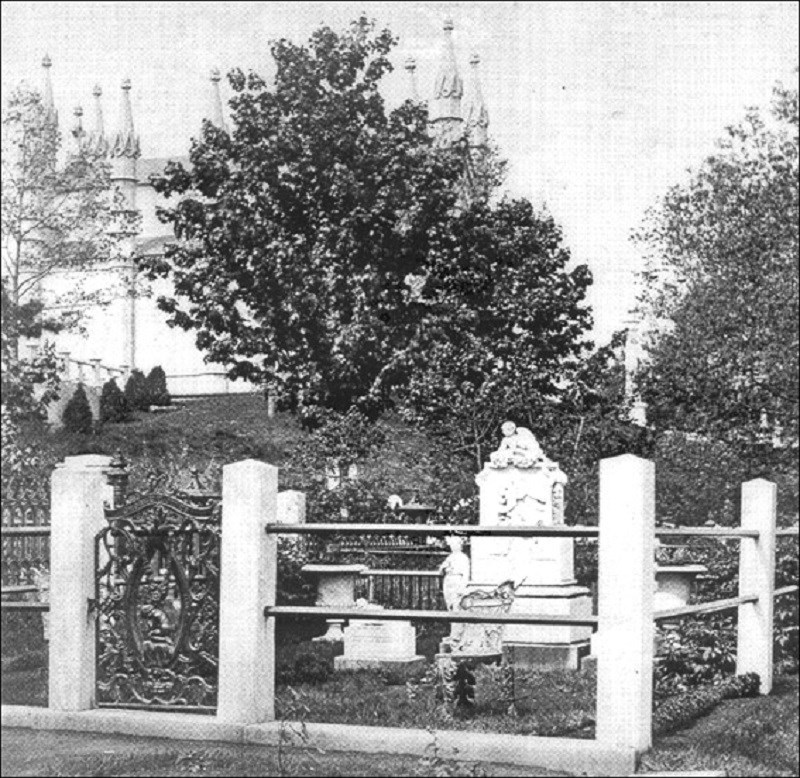

Photo 1: Stereographic view of Jones Lot, Mount Auburn Cemetery, 1860s.

The Joneses had embellished their lot with additional furnishings, much as they had decorated their home.

Drawing 5: Engraved view of Appleton Lot, Mount Auburn Cemetery, 1847.

(Courtesy of Mount Auburn Cemetery)

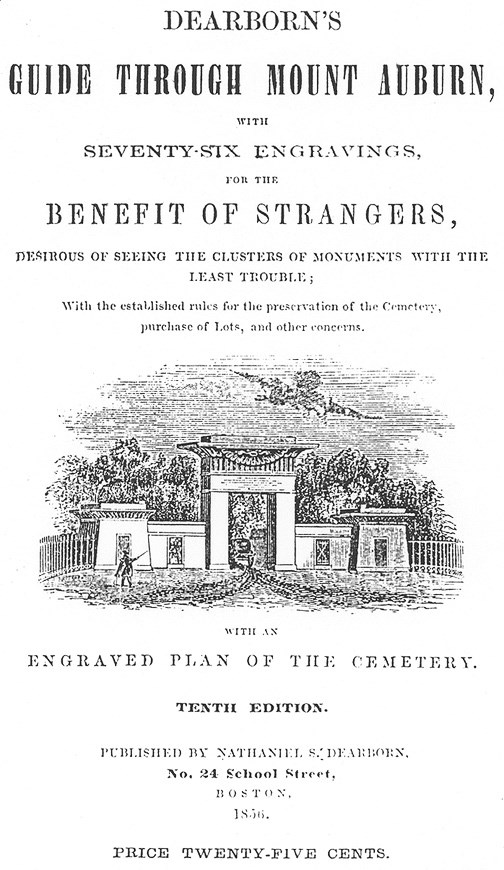

Questions for Photo 1 and Drawings 5 & 6

1. What objects do you see in Photo 1, and what would they have been used for?

2. What do the people in Drawing 5 appear to be doing? Are they paying any attention to the monument? What does this indicate about how people used the cemetery?

3. Can you identify the architectural style of the monument in Drawing 5? (Use additional sources to find out if you're not sure.)

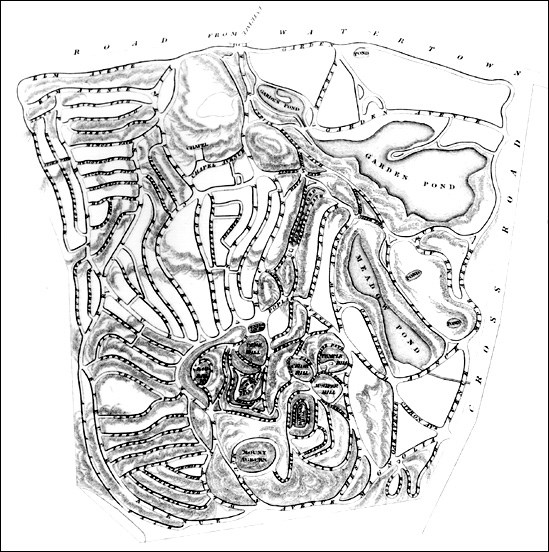

4. Study Drawing 6. Can you identify the architectural style of the entrance gate? (Use additional sources to find out if you're not sure.) Why might they have chosen that style?

5. What does the guide book cover tell you about some of the people who wanted to visit Mount Auburn? What edition is the guide book? What does this indicate about the popularity of the cemetery? How is this book similar to modern vacation guides?

6. After having seen Drawings 5 and 6, who do you think might visit the Jones Lot in Photo 1?

Putting It All Together

The following activities will help students discover the history of a cemetery in their community and how it compares to Mount Auburn Cemetery.

Activity 1: Map Mania

1. Using an enlarged copy of Map 2, the site map (the bigger the better), cut the map into 16 square pieces of roughly equal size.

2. Mix, and then have students draw pieces. Instruct them to try to piece the map back together.

3. Discuss as a class the clues they used to put the map back together. What made the task difficult? What made it easy? Would they describe the circulation system in Mount Auburn Cemetery as simple or complex?

Activity 2: Location is Everything

Ask students to identify the location of a local cemetery on a map of their community. Is the cemetery near the center of town, or is it near the edge? Then coordinate with your local library or historical society to arrange for students to see maps that show the location of the cemetery. Ask students to describe what the surrounding area looked like when the cemetery was first created. Why was the cemetery built in that location? Has the area around the cemetery changed substantially since it was founded?

Students may conduct additional research for substantiating evidence at your local town hall, library, or historical society. They might share their findings by writing an essay or article that compares the founding of your local cemetery with the founding of Mount Auburn Cemetery or making an exhibit comparing and contrasting the local cemetery with Mount Auburn Cemetery.

Activity 3: Observing the Landscape

Arrange for students to visit a local landscape, either a cemetery or park, and ask them to:

-

Compare the landscape of their local park or cemetery with that of Mount Auburn Cemetery. In what ways are they similar or different? In what ways is the overall plan similar to or different from Mount Auburn Cemetery?

-

Identify how people of their community use this landscape. How do they seem to feel about it?

-

Assess their emotional reaction to the landscape of their local cemetery and explain why they have that feeling.

Students may describe their experience either by writing about it or creating a graphic representation of it (drawing, painting, photograph, or collage.) Also, consider working with the organization that manages the cemetery to arrange a clean-up or preservation project at the cemetery.

Mount Auburn Cemetery: A New American Landscape--

Supplementary Resources

By looking at Mount Auburn Cemetery: A New American Landscape, students will learn about revolutionary changes in American landscape design and funerary practices that took place in the early 19th century. Those interested in learning more will find that the Internet offers a variety of interesting materials.

Mount Auburn Cemetery

Although still an active cemetery, Mount Auburn Cemetery was founded in 1831 as America’s first landscaped or garden cemetery. Comprising 175 acres, it has been nominated as a National Historic Landmark. For more information visit the Mount Auburn Cemetery website.

The Cultural Landscape Foundation

The Cultural Landscape Foundation is the only not-for-profit foundation in America dedicated to increasing the public’s awareness of the importance and irreplaceable legacy of cultural landscapes. Visit their website for more information on what cultural landscapes are and what they represent. Also learn about endangered landscapes and grassroots efforts to preserve them.

Boston National Historical Park

Boston National Historical Park is a unit of the National Park System. Visit the park's Web pages for the virtual Freedom Trail tour that shows the Granary, King's Chapel, and Copp's Hill burying grounds today.

Arnold Arboretum

The landscape and design at Mount Auburn Cemetery by the Massachusetts Horticultural Society helped to pave the way for Charles Sprague Sargent and Frederick Law Olmsted in their creation of the Arnold Arboretum, part of Boston City Park's Emerald Necklace.

Making of America

The Making of America site by Cornell University features a digital library of primary sources in American social history from the antebellum period through reconstruction. Included on the web site are images of many sources featuring and discussing Mount Auburn Cemetery, including a journal that printed Joseph Story's speech at the dedication of the cemetery.

Library of Congress: Historic American Buildings Survey (HABS)/ Historic American Engineering Record (HAER) Collection

Search the HABS/HAER collection for detailed drawings, photographs, and documentation from their architectural survey of Mount Auburn Cemetery. HABS/HAER is a division of the National Park Service.