Montane forests of the American Southwest are generally divided into four forest types based on the dominant tree species. With increasing elevation, they include three coniferous forests: ponderosa pine forest, mixed conifer forest, and spruce-fir forest. The fourth forest type is quaking aspen forest, a deciduous forest that grows in areas of past disturbance, primarily at the elevation of mixed conifer forest.

| Table 1. Summary of montane forests of the American Southwest. | ||||

| Ponderosa pine forest | Mixed conifer forest | Spruce-fir forest | Quaking aspen forest | |

| Site conditions | Relatively low elevation; generally flat to moderately steep topography. | Mid elevation; often moderately steep, sometimes dissected topography. | Upper elevation; usually steep topography. | Mid elevation; often moderately steep topography. |

| Tree species | Ponderosa pine, along with pinyon pine and junipers in understory at low elevation and Douglas-fir, white fir, and quaking aspen at high elevation. | Ponderosa pine, Douglas-fir, white fir, and quaking aspen on dry sites. Also subalpine fir, blue spruce, and Engelmann spruce on moist sites. | Similar to mixed conifer forest at low elevation, but primarily Engelmann spruce, subalpine fir, and blue spruce at high elevation. | Quaking aspen, with ingrowth |

Historical stand structure | Open canopy with dense herbaceous layer. | Likely open to closed canopy with variable herbaceous layer. | Likely depended on successional age. | Likely open to closed deciduous canopy with dense herbaceous layer at young successional age, followed by ingrowth of conifers. |

Historical fire regime | Frequent, low-severity surface fires. | Mixed-severity fire regime with frequent, low-severity fires and smaller areas of infrequent, high-severity | Poorly known, but likely mixed-severity at low elevation (see mixed conifer forest) and possibly a crown fire regime of infrequent, high-severity fires at high elevation. | Initiated by crown fires and thereafter similar to adjacent coniferous forest but likely with lower frequency and intensity. |

Major historical human impacts* | Fire exclusion and logging. | Fire exclusion. | Fire exclusion at low elevations; unknown at high elevation. | Fire exclusion. |

Historical changes in stand structure* | Increased density of canopy and understory trees. | Increased density of canopy and understory trees followed by decreases in at least some | Similar to mixed conifer forests at low elevation. Unknown at high elevation, but likely related to successional aging. | Likely related to successional aging. |

Historical changes in tree species | Increases of white fir and decreases of quaking aspen at mid and high elevations. | Increases of white fir at low elevation and subalpine fir at high elevation, followed by decreases in these and quaking aspen. | Increases of subalpine fir followed by decreases in it and quaking aspen at low elevation. Unknown at high elevation, but likely related to successional aging. | Increases of conifers and decreases of quaking aspen with successional aging. |

Current fire | Mixed-severity. | Mixed-severity (with extensive crown fire) or crown fire. | Same as mixed conifer forest at low elevation and possibly same as historical fire regime at high elevation. | Unknown, but changes are likely similar to those of adjacent coniferous forest. |

| *Excludes recent impacts such as management fire, climate change, and air pollution because their effects are not well known in the American Southwest. | ||||

The stand structure of each forest consists of a canopy layer (overstory) of the tallest trees and an understory made up of herbaceous plants, shrubs, and shorter trees, including species with the genetic potential to grow into the canopy. Details of stand structure (height, density, etc.) and species composition vary by and within forest type. Stand structure and species composition are determined primarily by moisture and disturbance, which in turn are influenced by elevation, topographic position, and slope exposure.

Common canopy tree species are (in approximate order of increasing elevation) ponderosa pine, Douglas-fir, southwestern white pine (Pinus strobiformis), quaking aspen, white fir (Abies concolor), limber pine (Pinus flexilis), blue spruce (Picea pungens), subalpine fir (Abies lasiocarpa), corkbark fir (Abies lasiocarpa var. arizonica), Engelmann spruce (Picea engelmannii), and bristlecone pine (Pinus aristata).

Understory tree species include junipers (e.g., Utah juniper: Juniperus osteosperma), pinyon (piñon) pines (e.g., Colorado pinyon: Pinus edulis), oaks (especially Gambel oak: Quercus gambelii), New Mexico locust (Robinia neomexicana), and Rocky Mountain maple (Acer glabrum).

Common shrubs include sages (Artemisia spp.), Gambel oak (which may be shrubby or tree-like), buckbrush (Ceanothus fendleri), manzanitas (Arctostaphylos spp.), creeping mahonia (Mahonia repens), honeysuckles (Lonicera spp.), currants (Ribes spp.), myrtleleaf huckleberry (Vaccinium myrtillus), ninebark (Physocarpus monogynus), dwarf or common juniper (Juniperus communis), and snowberry (Symphoricarpus oreophilus). Herbaceous plants include graminoids (grasses and grasslike plants) such as bluegrasses (Poa spp.), bromes (Bromus spp.), fescues (Festuca spp.), muhlys (Muhlenbergii spp.), and sedges (Carex spp.) as well as forbs (broad-leaved herbs) such as paintbrushes (Castilleja spp.), Geraniums (Geranium spp.), strawberries (Frageria spp.), fleabanes (Erigeron spp.), lupines (Lupinus spp.), groundsels (Senecio spp.), goldenrods (Solidago spp.), and bracken fern (Pteridium aquilinum).

Ponderosa Pine

Photograph courtesy of Arizona Historical Society, Flagstaff, Ray Housley Collection

Ponderosa pine forest makes up 80% of the montane forests in the Southwest. It includes the largest contiguous ponderosa pine forest in North America, extending from west-central New Mexico to the region of Flagstaff, Arizona. Other large areas occur in the southern Rocky Mountains and Jemez Mountains in northern New Mexico and the Kaibab Plateau in northern Arizona.

Prior to settlement by non-indigenous peoples, ponderosa pine forest was generally characterized by relatively open stand structure with large, widely spaced ponderosa pines and a dense, grass-dominated herbaceous layer. Written descriptions from the time include:

We came to a glorious forest of lofty pines...every foot being covered with the finest grass, and beautiful broad grassy vales extended in every direction. The forest was perfectly open... (Beale 1858)

Descriptions of open forest are supported by historical photographs, historical data (e.g., Lang and Stewart 1910), reference sites relatively unaffected by non-indigenous peoples (Fulé et al. 2002), and research that reconstructed past forest structure and composition based on tree rings of current living and dead trees (e.g., Fulé et al. 1997). The open stand structure was maintained by a fire regime of frequent, low-severity surface fires that thinned tree populations; research on fire history indicates that stands burned approximately every decade (Swetnam and Baisan 1996).

Stand structure and species composition depended on soil moisture. At lower, drier elevations, the canopy of ponderosa pines was very open and the understory had pinyon pines and junipers, reflecting proximity to pinyon-juniper vegetation. With more moisture at mid-elevations, ponderosa pine formed a denser but still open canopy (above) with ponderosa pine and sometimes Gambel oak dominating the understory. At higher elevations, the canopy was more diverse with ponderosa pine joined by Douglas-fir, quaking aspen, and white fir in forming the transition to mixed conifer forest.

Succession in ponderosa pine forest before the influence of non-indigenous peoples is best considered on an individual tree scale, because stand- and landscape-scale disturbances such as crown fire were uncommon. Following the death of a large tree, fire eventually consumed it, creating a microsite relatively rich in nutrients and free of competitors. Although tree regeneration was uncommon (White 1985), ponderosa pine seedlings established in years when seeds and sufficient moisture were available; otherwise the microsite was colonized by herbs. Where ponderosa pine regeneration occurred, clusters of seedlings and saplings were thinned by surface fires, but eventually canopy trees were replaced.

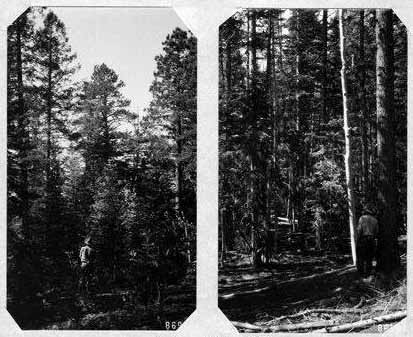

Mixed Conifer Forest

Photographs from Lang and Stewart (1910).

Mixed conifer forest makes up 13% of the montane forest in the Southwest. All areas are relatively small, widely separated and surrounded by much larger areas of ponderosa pine forest. The largest areas of mixed conifer forest include the Kaibab Plateau and the San Francisco Peaks in northern Arizona, the White Mountains in east-central Arizona, and the southern Rocky Mountains and Jemez Mountains in northern New Mexico.

Stand structure prior to settlement by non-indigenous peoples is not well known because there are no descriptions or reference sites, and forest reconstruction studies are subject to greater error than the studies of ponderosa pine forest (but see Fulé et al. 2003a). However, with more moisture at higher elevations, most mixed conifer stands were likely denser than ponderosa pine forests, a conclusion suggested by historical photographs (above) and historical data on canopy-sized trees (Lang and Stewart 1910). Mixed conifer forest had a mixed-severity fire regime (e.g., Fulé 2003a). Most sites burned in high-frequency, low-severity surface fires similarly but somewhat less frequently than ponderosa pine forest (Swetnam and Baisan 1996). These fires occasionally crowned, especially in dense stands in dry years (cf. Margolis et al. 2007). The result was a patchy landscape mosaic that reflected the diversity and interaction of topography, vegetation, and fire (e.g., Moir 1993, White and Vankat 1993, Fulé 2003a).

As implied by the name mixed conifer forest, species composition was variable, depending primarily on moisture, which is influenced by elevation, topographic position, and slope exposure. The mix of canopy species included ponderosa pine, Douglas-fir, quaking aspen, white fir, limber pine, blue spruce, subalpine fir, corkbark fir, and Engelmann spruce. Individual stands typically had three to five of these species in the canopy, although less diverse stands were present, especially of Douglas-fir. Relatively dry stands were generally dominated by a mix of ponderosa pine, Douglas-fir, quaking aspen, and white fir. Such stands were widespread at low elevations (where they were transitional with moist ponderosa pine forest). At higher elevations, these stands were more restricted to dry sites, such as ridgetops and south and west slope exposures. Moister stands had a greater abundance of subalpine fir or corkbark fir and Engelmann and blue spruce in the canopy. Such stands were widespread at high elevations (where they were transitional with spruce-fir forest) and more restricted to valley bottoms and north and east slope exposures at lower elevations.

Succession in mixed conifer forest (and low-elevation spruce-fir forest) occurred at both the single tree and stand scales, reflecting the mixed-severity fire regime that included surface and crown fires. In areas where fires remained on the surface, succession occurred at the single tree scale, similar to ponderosa pine forest. In stands where fires crowned, succession often involved the initiation and growth of dense patches of young quaking aspen forest.

Spruce-fir Forest

Photograph courtesy of Arizona Historical Society, Flagstaff, William H. Switzer Collection.

Spruce-fir forest makes up only 4% of the montane forest in the Southwest. All areas are small, widely separated, and surrounded by larger areas of mixed conifer forest. The largest areas of spruce-fir forest occur on the San Francisco Peaks in northern Arizona, the White Mountains of east-central Arizona, and the southern Rocky Mountains and Jemez Mountains of northern New Mexico.

Stand structure prior to settlement by non-indigenous peoples has not been well studied. Structure likely depended on successional age and therefore may be similar to today’s structure (above). The fire regime is poorly known for the Southwest, but at relatively low elevations it was likely a mixed-severity regime similar to mixed conifer forest (Fulé et al. 2003a) and at higher elevations it may have been a crown fire regime characterized by high-severity, stand-replacing fires at intervals of one or more centuries. Succession following crown fire is unstudied for the Southwest, but tree density may have increased early in succession and decreased in older stands. Structure also depended on elevation, as stands were more open and had shorter canopies closer to treeline.

Stand composition was dominated by Engelmann or blue spruce, often with subalpine or corkbark fir and some quaking aspen. Low elevation stands had occasional ponderosa pines and Douglas-firs indicative of transition with mixed conifer forest. Some treeline stands were dominated by bristlecone pine. Tree species composition also depended on successional age, with younger stands dominated by Engelmann spruce, quaking aspen, or both. Subalpine or corkbark fir may have co-established with Engelmann spruce or followed several decades later.

Quaking Aspen Forest

Photo by Betty Huffman

Quaking aspen forest makes up only 4% of the montane forest in the Southwest. It typically occurs in small to large patches where crown fire had burned mixed conifer forest, or where other stand-replacing disturbance had occurred (right). Even distant patches are easily visible because aspens are lighter green than conifers in summer, yellow in fall, and leafless in winter. Extensive areas of quaking aspen forest occur on the San Francisco Peaks in northern Arizona, the White Mountains in east-central Arizona, and the southern Rocky Mountains and Jemez Mountains of northern New Mexico.

Stand structure prior to settlement by non-indigenous peoples is poorly understood. However, because structure depends on successional age and stand-initiating disturbances occurred in the past and present, the range of stand structures was likely similar to today (although there are likely proportionately fewer young and more old stands today). The fire regime of quaking aspen forest generally mimicked that of adjacent stands of coniferous forest; however, aspen stands are less flammable and therefore had lower fire frequency and severity.

In terms of species composition, aspen dominated the canopy of all stands and conifers were present in the understory in all except very young or semi-permanent stands. Conifers included ponderosa pine, white fir, subalpine or corkbark fir, and blue or Engelmann spruce, depending on site characteristics and composition of adjacent conifer stands.

Photo by Betty Huffman

Succession following crown fire (or other stand-replacing disturbance) began with aspen resprouting from root systems of trees whose trunks were killed. Fire stimulated sprouting. A dense, even-aged canopy formed in a few decades. At some point in succession, depending on the availability of seed sources, conifers usually invaded (right). Mature stands, therefore, had a well-developed canopy of aspen and an understory with a mixture of aspen and conifers. The understory conifers, if present, had the potential to overtop and replace the relatively short-lived (100-150 years) aspen in succession, converting stands into mixed conifer forest. However, large stands where sources of conifer seeds were distant may have had little ingrowth of conifers and were semi-permanent.

Part of a series of articles titled Montane Forests of the Southwest.

Last updated: October 5, 2016