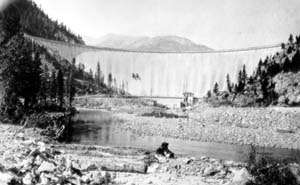

In 1907, engineers with the U.S. Reclamation Service met at Great Falls, Montana, to open bids for a dam on the Sun River. But, alas, there were no bids to open. So remote was Montana’s Sun River that no contractor wanted to venture there. Willow Creek Dam, the first dam built on the Sun, thus had to be built by “force account,” meaning Reclamation had to use its own personnel and equipment. Twenty years later, when construction began on Gibson Dam, with a contractor hired, the nearest railroad was still a distant 23 miles. Situated in the Lewis and Clark National Forest, just west of Augusta, Montana, (population 284) Gibson Dam today remains off the beaten track, although its place is central in the history of structural dam design.

Constructed between 1926 and 1929, Gibson Dam holds the distinction of being the first American dam not only to be analyzed according to the trial-load method, as were Pathfinder and Buffalo Bill dams, but designed using it. The trial-load method relies on mathematical equations to determine stresses and strains acting on a dam. Gibson Dam, like Pathfinder and Buffalo Bill dams, functioned as an arch and gravity dam combined, meaning the load was distributed between horizontal arches (pushing the load out to canyon walls), and vertical cantilevers (directing the load down to the dam’s foundation). The method, historian Norman Smith writes, “put arch dam design on a much sounder footing” and would be used later in dams as large and as famous as Hoover on the Colorado River.

Gibson Dam, standing 199 feet high with a crest length of 960 feet, is an imposing, concrete half-moon able to store 99,000 acre feet of water in its reservoir. An acre foot is enough water to cover one acre a foot deep, or 325,851 gallons. Because a gallon of water weighs 8.33 pounds, an acre foot of water weighs 1,357 tons. Imagine how rock-solid Gibson Dam needed to be to store not just one acre foot of water, but 99,000 acre feet.

To deal with these weighty issues, engineers with the Bureau of Reclamation started to build scale models of dams. An exact replica of Gibson Dam was one of the first two built (the other was the Stevenson Creek experimental dam in California). The models, Popular Science magazine reported in August 1929, were made of the same material to be used in the dam, even if it meant carting dirt and bits of rock a thousand miles to the lab. Once the model was complete, engineers created a miniature flood by pressing heavy mercury against the upstream face of the model dam, testing to determine how high its wall could go before it gave way. The formula for Gibson Dam demanded that the dam’s base be built to a maximum width of 117 feet, tapering to 15 feet wide at the top.

The Utah Construction Company of Ogden won the contract in September 1926 with a bid of $1.5 million, and excavation began that December. Utah Construction’s project superintendent, Albert E. Paddock was among a handful of men killed on the project. With the dam just months from completion, Paddock was struck by a workman who tumbled to his death from a tower above.

As the dam was a prototype of Reclamation’s trial-load method, engineers sought to collect as much information as they could, so workers inserted instruments to measure pressures, loads, and variations in temperature--behavioral data was collected until 1942. Gibson Dam, completed in 1929, faced a severe test in June 1964 when the Sun River Valley recorded its largest flood in history. Heavy rains and snowmelt from the Continental Divide sent floodwaters three feet over the top of the dam, leading Reclamation to conduct a variety of studies over the next decade and a half. Fearing that Gibson could not withstand a 100-year flood or an earthquake, Reclamation placed a concrete cap, anchored by knob-shaped rock bolts and costing $1.8 million, over the dam’s right abutment. Engineers added controlling equipment in the spillway gates, aeration piers on top of the dam to maintain its downstream face, and structural behavior monitors to keep an eye on stability.

Montana’s Sun River, known as Medicine River to the indigenous Blackfeet, rises near the Continental Divide and flows 130 miles southeast, where it empties into the Missouri at Great Falls. Lewis and Clark passed this way and camped at the mouth of the Sun on July 4, 1805, celebrating the day by distributing the last of their “ardent spirits” to the men of the Corps of Discovery. Lewis ventured ahead, explored all five of the Missouri’s “great falls” and wrote of seeing a thousand bison grazing east of the Sun River.

Only a half-century later, with the buffalo disappearing and their people decimated by a smallpox epidemic, the Blackfeet signed a treaty with the Federal Government, which established an Indian agency a half-mile upriver from the present town of Sun River, population 131. There, Indian agent A. J. Vaughan established an agency farm and oversaw the planting of vegetables, fruits, and grain. A decade later, when the U.S. Army established Fort Shaw a few miles west, Colonel John Gibbon looked to the Sun River, too. He ordered the post adjutant to survey and build a ditch to irrigate the post gardens and the flowers he planted along the parade grounds. The ditch, with a capacity of about 15 cubic feet per second, was considered a marvel, but the Federal Government’s larger commitment to irrigating the Sun River Valley had to await creation of the U.S. Reclamation Service in 1902.

The very next year, Reclamation conducted the first reconnaissance of the region, but it took a Montanan, Samuel Bostwick Robbins, to dream big about irrigating--and populating--the Sun River Valley. Robbins, a graduate of Yale’s Sheffield Scientific School, signed on as an engineer with the Reclamation Service in 1903 and, as Robert Autobee writes, began promoting the valley as “the greatest farming country under the dome of Heaven.” Following Robbins’s lead, the citizens of Great Falls formed a committee, went to Washington, D.C., and lobbied the Federal Government for an irrigation project. On February 26, 1906, their efforts paid off when the Secretary of the Interior authorized the Sun River irrigation project, which included plans to carve 206 farms out of the Fort Shaw military post, which had been abandoned in 1890.

It was amid the crumbling adobe walls and clogged sewer pipes of the old fort that Reclamation set up its offices. Here, weary pioneer farm families often spent their first night in the Sun River Valley, sleeping on the floor of the Reclamation office. By 1920, Reclamation had constructed three dams, an extensive system of canals, and laid out two towns, Fort Shaw and Simms, but the project’s finances were a mess. Few water users could repay their $60 an acre obligation to the government, and by the fall of 1923 the Federal Government had spent $4.7 million to water 50,579 acres valued at only $2 million.

The situation was bad enough that Elwood Mead, commissioner of the Bureau of Reclamation, went out to Great Falls in the summer of 1925. Heated words flew, Autobee writes, as Mead told the people of the Sun River Project that the Government “must put an end to supplying water to people year after year without requiring them to pay for it.” Even so, the recently completed “Fact Finders’ Report,” much of it written by Mead, directed Reclamation to improve life on its present projects rather than bring new ones online. The result for Reclamation’s Sun River Project was a new dam--Gibson Dam, a solid commitment by the Federal Government to put the past behind and meet the region’s water needs. Today, Gibson Dam and other units of the Sun River Project irrigate 91,000 acres, where principal crops are wheat, oats, barley, and alfalfa.

Visit the National Park Service Travel Bureau of Reclamation's Historic Water Projects to learn more about dams and powerplants.

Last updated: January 13, 2017