Last updated: July 13, 2023

Article

Monitoring the Health of Whitebark Pine Populations

NPS

Whitebark pine (Pinus albicaulis) is a five-needle pine that grows in high-elevation ecosystems in Western North America. Whitebark pine seeds were frequently used by Native Americans as a food sources and are a valuable food for birds, squirrels, and bears. Whitebark pine cones do not open when ripe or in fires, but are dispersed by Clark’s nutcrackers (Nucifraga columbiana), red squirrels (Tamiasciurus hudsonicus), and Douglas squirrels (Tamiasciurus douglasii) who extract seeds from the closed cones and then cache them in subalpine meadows for future retrieval.

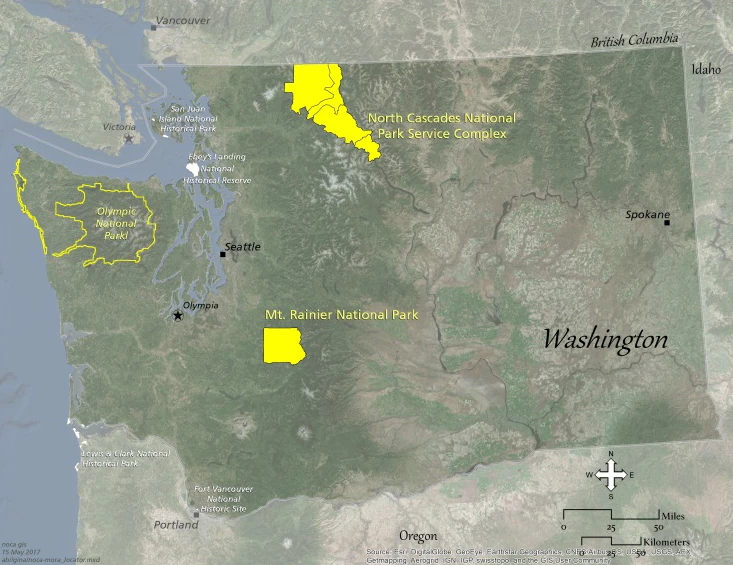

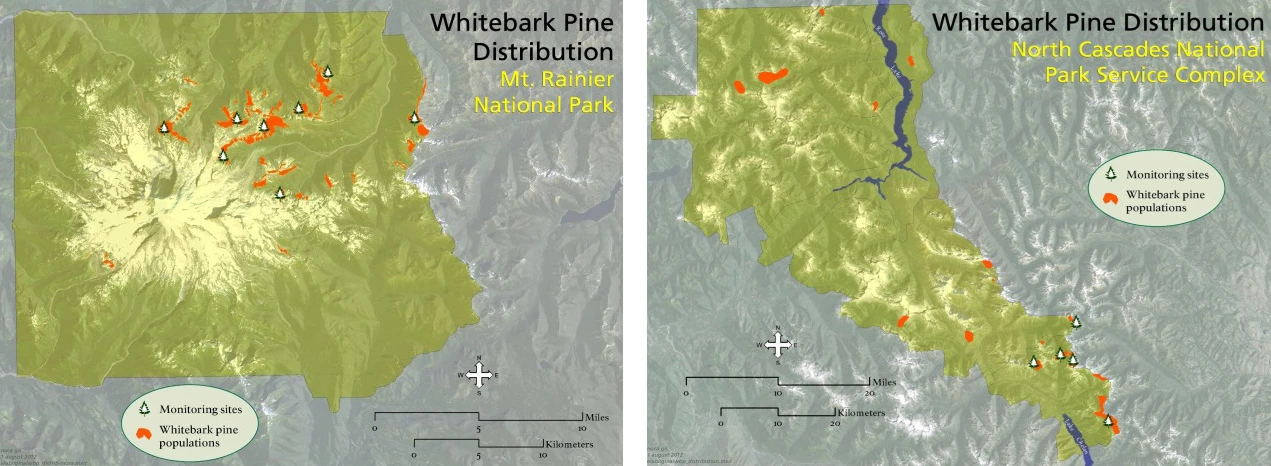

Distribution in Pacific Northwest Parks

Whitebark pine grows on cold, dry sites generally above 5,000’ (1524 m) and can be found in three national parks within the North Coast and Cascades Network (NCCN). In North Cascades National Park Service Complex (NOCA), 12 whitebark pine stands have been mapped extending from Silver Lake near the Canadian border south to Triplett Lakes near the southeast boundary (~ 3,922 ha). In Mount Rainier National Park (MORA), stands are concentrated in the northeast corner of the park near Sunrise (66 stands; a total of 1,193ha). In Olympic National Park (OLYM), whitebark pine is limited to three populations east of Mount Olympus.

NPS

Threats to Whitebark Pine Survival

Today, the long-term survival of white pine is threatened by an introduced fungus, blister rust (Cronartium ribicola) and the native mountain pine beetle (Dendroctonus ponderosae). Blister rust is a Eurasian fungus that was introduced to western North America in 1910 near Vancouver, B.C. The fungus is an obligate parasite and requires two hosts to complete its life cycle. Fungus spores disperse from gooseberries (Ribes spp.), louseworts (Pedicularis spp.), or paintbrushes (Castilleja spp.) and enter whitebark pine through needles. After several years, cankers are visible on branches or boles as the rust spreads girdling tree stems and finally killing the tree. Warmer climates and drier summers may allow blister rust to spread more quickly to the tree bole hastening tree death.

Why Monitor Whitebark Pine Health?

Whitebark pine is often referred to as a keystone species because it has a crucial role in the functions of high-elevation ecosystems. Often it is the first tree species to establish in subalpine meadows or on alpine ridges; its presence influences snowmelt patterns, soil development, and it provides important micro-sites for the establishment of other subalpine plant species. The National Park Service is responsible for protection of native ecosystem structure and function. We need to know the health (status) of these ecosystems to successfully protect or restore them.

Where Are We Monitoring?

Whitebark pine is a one component of the North Coast and Cascades Network Alpine and Subalpine Vegetation Monitoring Program. Whitebark pine study plots were established in eight stands in Mount Rainier and five stands in North Cascades in 2004. Trees, saplings, and seedlings have been monitored for diameter, height, status (live or dead), presence of blister rust, and mountain pine beetles at three times: 2004, 2009 and 2015/2016.

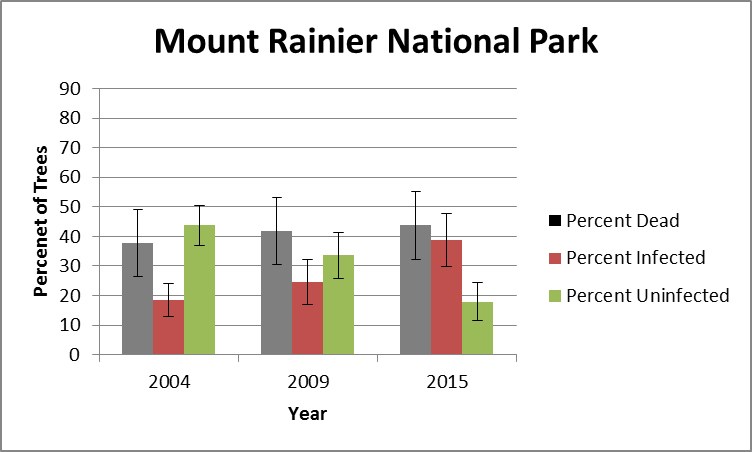

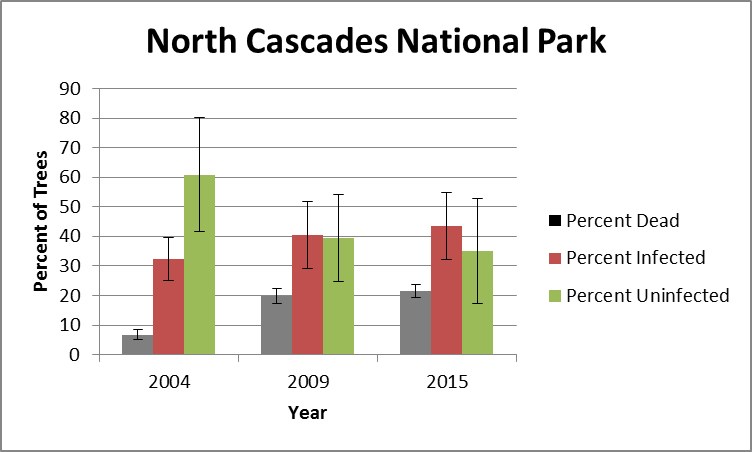

Population Status & Trends

The health of whitebark pine populations in Mount Rainier and North Cascades National Parks has steadily declined over the last decade. Mortality and infection rates have continued to increase while the numbers of uninfected trees has decreased.

In 2004, 44% of Mount Rainier whitebark pine trees were healthy (showing no signs of blister rust), 18 % were infected, and 38% of only 44% were dead. In 2015, only 18% of the population remained uninfected, infection rates had increased to 38%, and mortality had increased to 44%.

In North Cascades, baseline surveys indicated that 61% of trees were healthy, 32% were infected with blister rust, and only 7% of all whitebark pine were dead. By 2015, mortality had increased to 21%, infection rates to 44%, and only 35% were found to be uninfected.

For More Information

Journal Article

Rochefort, R.M.; Howlin, S.; Jeroue, L.; Boetsch, J.R.; Grace, L.P. Whitebark Pine in the Northern Cascades: Tracking the Effects of Blister Rust on Population Health in North Cascades National Park Service Complex and Mount Rainier National Park. Forests 2018, 9, 244.

Contact

Mignonne Bivin

Phone: 360-854-7335