Last updated: May 5, 2023

Article

Memories of Montpelier: Home of James and Dolley Madison (Teaching with Historic Places)

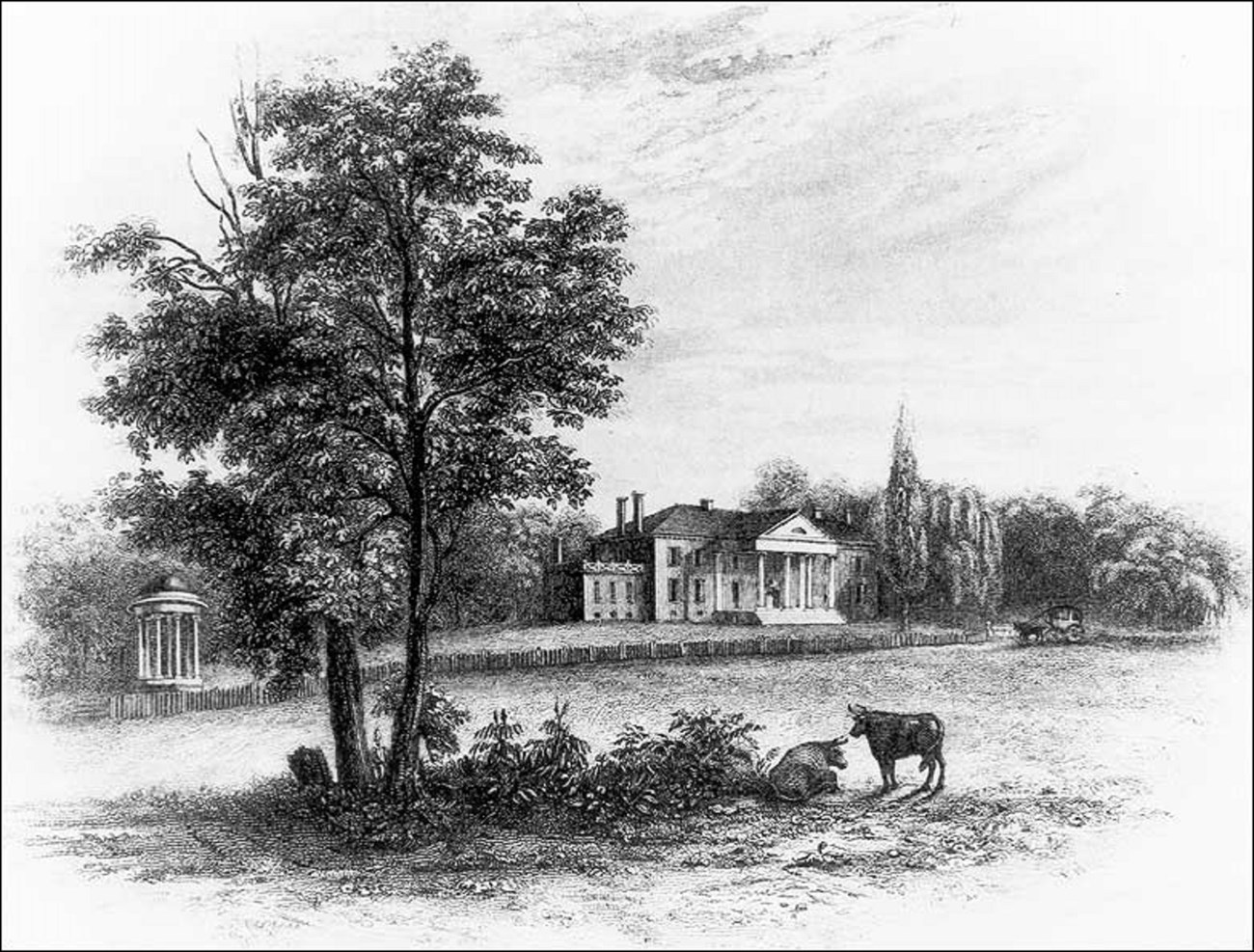

Reflecting back on her many visits to James and Dolley Madison’s plantation home, Dolley’s longtime friend, Margaret Bayard Smith, described the Montpelier she had grown to love:

...among the hills [at the foot of the Blue Ridge Mountains]..., is the paternal estate of Mr. Madison. Naturally fertile, but much improved by his judicious care, a comparatively small part is kept under cultivation, the greater part being covered with its native forests. A large and commodious mansion, designed more for comfort and hospitality than ornament and display, rises at the foot of a high wooded hill, which, while it affords shelter from the northwest winds, adds much to the picturesque beauty of the scene. The grounds around the house owe their ornaments more to nature than art, as with the exception of a fine garden behind, and a widespread lawn before the house, for miles around the ever varying and undulating surface of the ground is covered with forest trees.¹

Smith was not alone in her sentiment about Montpelier. In the early 19th century countless visitors expressed a great sense of pleasure in the place and in the people who lived there. They quickly understood how deeply James Madison (1751-1836) was rooted in his family estate. His grandparents had settled Montpelier in the early 1730s. In the late 1750s Madison’s father began building the house where Madison grew up and to which he returned permanently following his retirement as president in 1817. Madison enjoyed the opportunities and met the responsibilities of education and public service associated with the wealthy Southern gentry to which he belonged. Ultimately, he took part in the most crucial years of our nation’s development. His greatest contribution was his service as "Father" of the Constitution.

¹James B. Longacre and James Herring, eds., The National Portrait Gallery of Distinguished Americans (New York: Herman Bancroft, 1836).

About This Lesson

This lesson is based on the National Register of Historic Places registration file for "Montpelier," a National Trust for Historic Preservation/Montpelier historic structure report, and other sources about the social history of Montpelier.

Memories of Montpelier was written by Candace Boyer, a former Museum Educator at Montpelier. The lesson was edited by Fay Metcalf, education consultant, and the Teaching with Historic Places staff. TwHP is sponsored, in part, by the Cultural Resources Training Initiative and Parks as Classrooms programs of the National Park Service. This lesson is one in a series that brings the important stories of historic places into the classrooms across the country.

Where it fits into the curriculum

Topics: The lesson could be used in teaching units on early 19th-century American history. The lesson will help students gain a better understanding of James and Dolley Madison, of daily life at home, and of contemporary beliefs and behaviors regarding slavery.

Time period: 1801-1836

United States History Standards for Grades 5-12

Memories of Montpelier: Home of James and Dolley Madison relates to the following National Standards for History:

Era 3: Revolution and the New Nation (1754 to 1820s)

-

Standard 3A- The student understands the issues involved in the creation and ratification of the United States Constitution and the new government it established.Era 4: Expansion and Reform (1801 to 1861)

-

Standard 1A- The student understands the international background and consequences of the Louisiana Purchase, the War of 1812, and the Monroe Doctrine.

-

Standard 2D- The student understands the rapid growth of "the peculiar institution" after 1800 and the varied experiences of African Americans under slavery.

-

Standard 3A- The student understands the changing character of American political life in "the age of the common man."

-

Standard 4A- The student understands the abolitionist movement.

-

Standard 4C- The student understands changing gender roles and the ideas and activities of women reformers.

Curriculum Standards for Social Studies

National Council for the Social Studies

Memories of Montpelier: Home of James Madison relates to the following Social Studies Standards:

Theme I: Culture

-

Standard B - The student explains how information and experiences may be interpreted by people from diverse cultural perspectives and frames of reference.

-

Standard C - The student explains and gives examples of how language, literature, the arts, architecture, other artifacts, traditions, beliefs, values, and behaviors contribute to the development and transmission of culture.

Theme II: Time, Continuity and Change

-

Standard F - The student uses knowledge of facts and concepts drawn from history, along with methods of historical inquiry, to inform decision-making about and action-taking on public issues.

Theme III: People, Places, and Environment

-

Standard G - The student describes how people create places that reflect cultural values and ideals as they build neighborhoods, parks, shopping centers, and the like.

Theme V: Individuals, Groups, and Institutions

-

Standard A - The student demonstrates an understanding of concepts such as role, status, and social class in describing the interactions of individuals and social groups.

-

Standard E - The student identifies and describes examples of tensions between belief systems and government policies and laws.

Theme IX: Global Connections

-

Standard F - The student demonstrates understanding of concerns, standards, issues, and conflicts related to universal human rights.

Theme X: Civic Ideals, and Practices

-

Standard A - The student examines the origins and continuing influence of key ideals of the democratic republican form of government, such as individual human dignity, liberty, justice, equality, and the rule of law.

-

Standard C - The student locates, accesses, analyzes, organizes, and applies information about selected public issues - recognizing and explaining multiple points of view.

Objectives for students

1) To describe Montpelier and aspects of daily life there from James Madison’s tenure as secretary of state through his retirement years (1801-1836).

2) To explore the lives of James and Dolley Madison through the eyes of their contemporaries.

3) To examine the ideas and actions of the Madisons and others regarding slavery.

4) To evaluate a historic place and the people associated with it in their own community.

Materials for students

The materials listed below either can be used directly on the computer or can be printed out, photocopied, and distributed to students. The maps and images appear twice: in a low-resolution version with associated questions and alone in a larger, high-quality version.

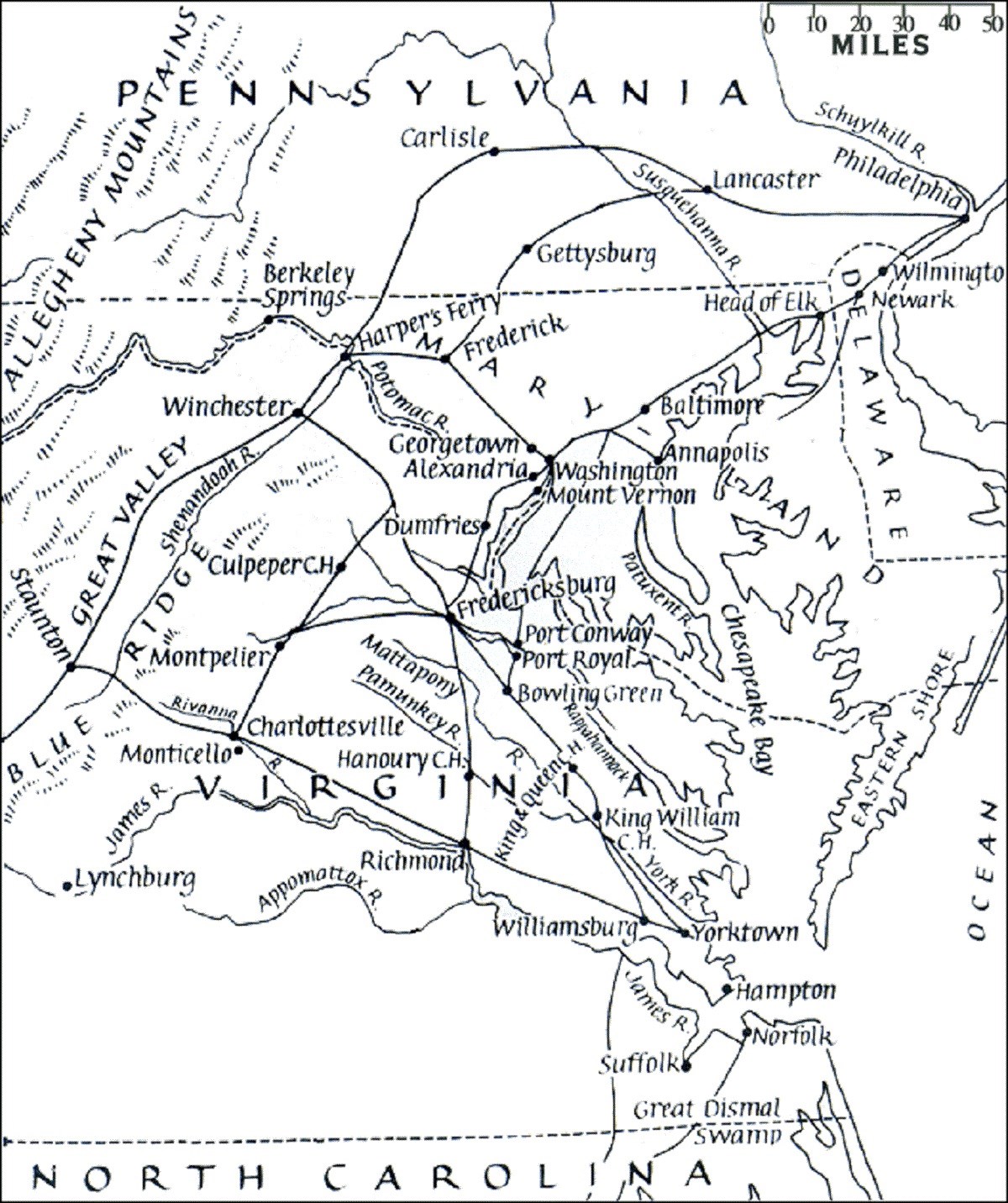

1) one map of the Chesapeake Bay region;

2) two readings from contemporary correspondence about daily life, slavery, and the Madisons at Montpelier;

3) one illustration and one photo of historical and modern views of Montpelier.

Visiting the site

Montpelier is one of 20 historic museum properties owned by the National Trust for Historic Preservation. It is located four miles southwest of Orange, Virginia, on Route 20, and lies approximately 25 miles north of Charlottesville and 70 miles south of Washington, D.C.

Getting Started

Inquiry Question

What might this place be?

Setting the Stage

James Madison was born on March 16, 1751, and his home was Montpelier, a 5,000-acre plantation estate located in the Piedmont of Virginia. In the late 1750s his father began building the house where Madison spent his youth. Prior to this the family lived on the Montpelier property in what was probably, at the very least, a modest frame house, typical of Piedmont Virginia architecture of the time. Montpelier remained Madison’s home throughout his adult life, although public service positions often called him away. Various public commitments included: the Continental Congress, 1780-1783; the Virginia Assembly, 1784-1787; the Federal Convention, 1787; the "new" Continental Congress, 1787-1789; the Federal Congress, 1789-1797; the Virginia Assembly, 1799-1800; secretary of state under Thomas Jefferson, 1801-1809; and president, 1809-1817. Even during these periods, however, Madison spent his long vacations at home.

In 1801 Madison, as the eldest son, inherited the estate his family had developed for more than 70 years. Following his retirement as president in 1817, Madison returned to Montpelier permanently. As he had anticipated, he and his wife, Dolley (1768-1849), received many visitors during this period. In fact, it was not uncommon for them to have as many as 25 guests or more requiring both room and board. Guests were a normal part of daily life on the plantations of Virginia gentry. Slavery was also a major part of plantation life. More than 100 enslaved African Americans provided the labor that supported and maintained Montpelier. The contributions of these slaves included agricultural labor, skilled craftsmanship, and domestic service.

Although it has undergone substantive modifications by its numerous owners since Madison, Montpelier’s setting, main house, and grounds reflect the Madison era and offer useful insights into the daily life of the "last founding father" and a large Virginia plantation home in the early 19th century.

Locating the Site

Map 1: Virginia and the Chesapeake Bay region.

Several visitors to Montpelier have left interesting comments about the house and its location. The earliest account is found in a diary entry of Anna Brodeau Thornton:

Sptr. 5th 1802. arrived at Mr. Madison’s country seat, about 110 miles from the City of Washington and situated in Orange County Virginia 5 miles from Orange Court House on one of the mountains...it is in a wild and romantic country, very generally covered with fine flourishing timber & forest trees.¹

In December 1824, while visiting Thomas Jefferson at his Virginia plantation home, Monticello, Congressman George Ticknor drafted a letter to a friend describing the trip he and his companion, congressman and orator Daniel Webster, made from Washington to Montpelier:

We have had an extremely pleasant visit in Virginia thus far, and have been much less annoyed by bad roads and bad inns than we supposed we should be, though both are certainly vile enough. We left Washington just a week ago, and came seventy miles in a steamboat, to Potomac Creek, and afterwards nine miles by land, to Fredericksburg....

On Saturday morning we reached Mr. Madison’s, at Montpellier [sic]...a very fine, commanding situation, with the magnificent range of the Blue Ridge stretching along the whole horizon in front, at the distance of from twenty to thirty miles.²

Questions for Map 1

1. Examine Map 1 and read the notes that accompany the map above. Now locate Washington, D.C., Montpelier, and Fredericksburg, Virginia.

2. What is the location of Montpelier in relation to other important towns and cities of the region during Madison’s time? to natural features? to transportation routes? How might these elements have contributed to the movement of people and goods into and out of this place?

3. How many miles is it from Washington, D.C., to Montpelier? from Montpelier to Monticello (Thomas Jefferson’s plantation home near Charlottesville)? from Fredericksburg to Montpelier? If the average travel time was approximately 25 miles a day, how many days would it have taken Anna Thornton to get from Washington to Montpelier according to Map 1? according to her diary entry? What might account for the differences?

4. Why do you think Congressman Ticknor described the roads he traveled on as "certainly vile enough"? How might this have influenced travel?

5. What mountains do visitors to Montpelier describe as being quite beautiful and close to Montpelier? How many miles is it from Montpelier to those mountains? Of what major mountain range are those mountains a part? How might the mountains have impacted the house’s location?

¹Diary of Anna B. Thornton (Mrs. William Thornton), 5 September 1802, Library of Congress.

²George Ticknor, Life, Letters, and Journals of George Ticknor (Boston: James R. Osgood and Company, 1876), vol. I, 346.

Determining the Facts

Reading 1: Daily Life at Montpelier

The following passage details the daily life of James and Dolley Madison but does not address what life was like for the enslaved men, women, and children who also lived at Montpelier.

Margaret Bayard Smith, a friend and admirer of the Madisons, made several trips to Montpelier from her home in Washington, D.C. One visit was recorded in this letter:

August 4th [1809], Montpelier, Wednesd. even.

The sadness which all day hung on my spirits was instantly dispelled by the cheering smile of Mrs. Madison and the friendly greeting of our good President. It was near five o’clock when we arrived, we were met at the door by Mr. M who led us in the dining room where some gentlemen were still smoking segars [sic] and drinking wine. Mrs. M. enter’d the moment afterwards, and after embracing me, took my hand, saying with a smile I will take you out of this smoke to a pleasanter room. She took me thro’ the tea room to her chamber which opens from it. Everything bespoke comfort, I was going to take my seat on the sopha [sic], but she said I must lay down by her on her bed, and rest myself, she loosened my riding habit, took off my bonnet, and we threw ourselves on her bed. Wine, ice, punch and delightful pine-apples were immediately brought. No restraint, no ceremony. Hospitality is the presiding genius of this house, and Mrs. M. is kindness personified. She enquired why I had not brought the little girls; I told her the fear of incommoding my friends. ‘Oh,’ said she laughing, ‘I should not have known they were here, among all the rest, for at this moment we have only three and twenty in the house.’ ‘Three and twenty,’ exclaimed I! ‘Why where do you store them?’ ‘Oh we have house room in plenty.’ This I could easily believe, for the house seemed immense. It is a large two story house....1

Mary Cutts, Dolley Madison’s niece, lived at Montpelier for a time in her youth after Madison’s retirement in 1817. Her memoir of her life there contains detailed descriptions of daily life:

[Mr. Madison’s] house was the resort of the distinguished men of the time; foreigners, tourists, artists and writers failed not to visit himself and Mr. Jefferson....

Mrs. Madison soon fell in with the Country customs. Barbecues were then at their height of popularity. To see the sumptuous board spread under the forest oaks, the growth of centuries, animals roasted whole, everything that a luxurious country could produce, wines, and the well filled punch bowl, to say nothing of the invigorating mountain air, was enough to fill the heart...with joy!... At these feasts the woods were alive with guests, carriages, horses, servants and children--for all went--often more than an hundred guests. All happy at the prospect of a meeting, which was a scene of pleasure and hilarity. The laugh with hearty good will, the jest, after the crops, "farmer’s topics" and politics had been discussed. If not too late, these meetings were terminated by a dance.2

Congressman George Ticknor described his impressions in a letter written during his December 1824 trip to Montpelier with congressman and famous orator Daniel Webster:

We were received with a good deal of dignity and much cordiality, by Mr. and Mrs. Madison, in the portico, and immediately placed at ease....

We breakfasted at nine, dined about four, drank tea at seven, and went to bed at ten; that is, we went to our rooms, where we were furnished with everything we wanted, and where Mrs. Madison sent us a nice supper every night and a nice luncheon every forenoon. From ten o’clock in the morning till three we rode, walked, or remained in our rooms, Mr. and Mrs. Madison being then occupied. The table is very amble [ample] and elegant; and somewhat luxurious; it is evidently a serious item in the account of Mr. M’s happiness, and it seems to be this habit to pass about an hour, after the cloth is removed, with a variety of wines of no mean quality.3

After first visiting Monticello (Jefferson’s Virginia plantation home), Margaret Bayard Smith brought her family along when she made another of her visits to Montpelier in August of 1828. The party was caught in a sudden rainstorm and became disoriented in the heavily wooded countryside:

Having lost ourselves in the mountain road which leads thro’ a wild woody track of ground, and wandering for some time in Mr. Madison’s domain, which seemed interminable, we at last reached his hospitable mansion....We drove to the door. Mr. M. met us in the Portico and gave us a cordial welcome. In the Hall Mrs. Madison received me with open arms and that overflowing kindness and affection which seems part of her nature. We were first conducted into the Drawing room, which opens on the back Portico and thus commands a view through the whole house, which is surrounded with an extensive lawn, as green as spring; the lawn is enclosed with fine trees, chiefly forest, but interspersed with weeping willows and other ornamental trees, all of the most luxuriant growth and vivid verdure. It was a beautiful scene! The drawing-room walls are covered with pictures, some very fine, from the ancient master, but most of them portraits of most distinguished men....The mantelpiece, tables in each corner and in fact wherever one could be fixed, were filled with busts, and groups of figures in plaster, so that this apartment had more than the appearance of a museum of the arts than of a drawing room. It was a charming room, giving activity to the mind, by the historic and classic ideas that it awakened.4

Questions for Reading 1

1. Who were some of the people who visited Montpelier? Why did they come? How did they describe Montpelier’s main house and natural surroundings? the Madisons? daily life?

2. What kinds of activities did the Madisons provide for their guests?

3. Do the accounts allow you to visualize the house and the grounds of Montpelier? Which account is most helpful?

4. Why would historians consider these documents important?

1Gaillard Hunt, ed., The First Forty Years of Washington Society: Portrayed by the Family Letters of Mrs. Samuel Harrison Smith (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1906), 81-82.

2Mary Cutts Memoir, Cutts Collection, Library of Congress.

3George Ticknor, Life, Letters, and Journals of George Ticknor (Boston: James R. Osgood and Company, 1876) vol. I, 346-47.

4Gaillard Hunt, 232-34.

Determining the Facts

Reading 2: Slavery at Montpelier

The following reading provides only a small representation of what slavery was like at Montpelier. Many of the viewpoints depict white Americans, particularly enslavers. While an excerpt from an enslaved man is included (Paul Jennings), his viewpoint does not speak for the other men, women, and children at Montpelier. Madison is described as the Father of the Constitution, a man dedicated to the principles of liberty and freedom, yet he sought to use the forced labor of people of African descent to enrich himself, his family, and other enslavers.

Before departing for Philadelphia in November 1790, James Madison wrote instructions for Montpelier’s overseer and slaves that included many details about the proper amount of "Negroe" food rations, as well as the directions to provide shelter for the cattle and to "fallow with the large plows all the ground for oats & Corn." He concluded his instructions to his overseer with the following instruction: "To treat the Negroes with all the humanity & kindness consistent with their necessary subordination and work."1

Upon visiting then-Secretary of State Madison at Montpelier in 1807, Sir Augustus John Foster, the British minister, recorded these observations in his journal:

The Negro habitations are separate from the dwelling house both here and all over Virginia, and they form a kind of village as each Negro family would like, if they were allowed it, to live in a house by themselves. When at a distance from any town it is necessary they should be able to do all kind of handiwork; and accordingly, at Montpellier [sic] I found a forge, a turner’s shop, a carpenter and wheelwright. All articles too that are wanted for farming or the use of the house were made on the spot, and I saw a very well constructed wagon that had just been completed.2

In 1824 during General Marquis de Lafayette’s much heralded trip through America, he and his secretary, Auguste Levasseur, spent four days at Montpelier. Levasseur recorded these impressions in his journal:

Mr. Madison is now seventy-four years of age; but his body, which has been but little impaired, contains a mind still young, and filled with a kind sensibility....

I will not enter into particulars concerning the management of Mr. Madison’s plantation: it is exactly what might be expected from a man distinguished by good taste and love of method, but unable to employ other labourers than slaves; who, whatever may be their gratitude for the good treatment of their master, must always prefer their own present ease to the increase of his wealth.

The four days we spent at Mr. Madison’s were agreeably divided between walks about his fine estate, and the still more engaging conversations that we enjoyed in the evenings, on the great interests of America, which are known to be so dear to Lafayette. The society [guests] which Madison assembled [on this occasion] at Montpellier [sic] was...com-posed of neighbouring [sic] planters, who appeared to me, in general, at least as intimately acquainted with the great political questions of their country, as those of agriculture. General Lafayette, who, while he appreciates the unfortunate position of slaveholders in the United States, and cannot overlook the greater part of the obstacles which oppose an immediate emancipation of the blacks, still never fails to take advantage of an opportunity to defend the right which all men, without exception, have to liberty, introduced the question of slavery among the friends of Mr. Madison. It was approached and discussed by them with frankness, and in such a manner as to confirm the opinion I had before formed of the noble sentiments of the greater part of the Virginians, on that deplorable subject. It seems to me that slavery cannot subsist much longer in Virginia: for the principle is condemned by all enlightened men; and when public opinion condemns a principle, its consequences cannot long continue.3

The young traveler from Massachusetts, George C. Shattuck, revealed more about Madison in this 1835 letter to his father, a doctor:

[Madison] is very cheerful, sprightly, much interested in what is going on in the world. He inquired a good deal about the factories and the operatives. He thinks that Virginia can employ her slave labor in this way with great profit, and that the Northern states will not be able to manufacture so cheaply as labor is so high with them. He also inquired about Washington and seemed to take great interest in the proceedings of congress.4

Paul Jennings was born a slave at Montpelier in 1799 and later became Madison’s "body servant" (personal slave) until Madison’s death. He shared his recollections of the Madisons:

Mrs. Madison was a remarkably fine woman. She was beloved by every body in Washington, white and colored....

Mr. Madison, I think, was one of the best men that ever lived. I never saw him in a passion, and never knew him to strike a slave, although he had over one hundred; neither would he allow an overseer to do it. Whenever any slaves were reported to him as stealing or ‘cutting up’ badly, he would send for them and admonish them privately, and never mortify them by doing it before others. They generally served him very faithfully.5

After Madison’s death, Daniel Webster purchased Paul Jennings’ freedom. Jennings was grateful and soon advocated freedom for all his people. He helped to plan a large-scale escape of slaves from Washington, D.C. In an 1848 letter he explained to Senator Webster why he felt the need to act in such a way:

Honored Friend,

A deep desire to be of help to my poor people has determined me to take a decided step in that direction. My only regret is that I shall appear ungrateful, in thus leaving with so little ceremony, one who has been uniformly kind and considerate and has rendered each moment of service a benefaction as well as pleasure. From the daily contact with your great personality which it has been mine to enjoy, has been imbibed a respect for moral obligations and the claims of duty. Both of these draw me towards the path I have chosen.

Jennings6

Questions for Reading 2

1. How did Sir Augustus John Foster describe the slave quarters? What different kinds of labor did the slaves provide? Why?

2. How did Paul Jennings regard his master and mistress? From what you know of his later life, what were his beliefs and behaviors regarding slavery? Were these attitudes and actions inconsistent? Why or why not?

1Ralph Ketcham, James Madison: A Biography (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1990), 374, 703.

2Richard Beale Davies, ed. Jeffersonian America: Notes on the United States of America Collected in the Years 1805-6-7 and 11-12 by Sir Augustus John Foster, Bart. (San Marino: Huntington Library, 1954), 139-42.

3Auguste Levasseur, Lafayette in America in 1824 and 1825, Or, Journal of Travels in the United States (New York: Gallaher and White, 1829), 221-22.

4George C. Shattuck, Jr. to Dr. George C. Shattuck, 24 January 1835, Massachusetts Historical Society, Boston, Massachusetts.

5Paul Jennings, A Colored Man’s Reminiscences of James Madison (Brooklyn: George C. Beadle, 1865). Reprinted in White House History, I, no. 1 (1983), 50

6G. Franklin Edwards and Michael R. Winston, "Commentary: The Washington of Paul Jennings--White House Slave, Free Man, and Conspirator for Freedom," White House History, I, no.1 (1983): 61.

Visual Evidence

Photo 1: Montpelier

Questions:

1. Consider the illustration of historic Montpelier and the modern photo. How do you think this building has changed over time?

2. What can you learn about the time period from studying this photo? Can you infer anything about the people who live in this house from the photo?