Last updated: July 14, 2017

Article

The French Connection: The McLoughlins in Paris

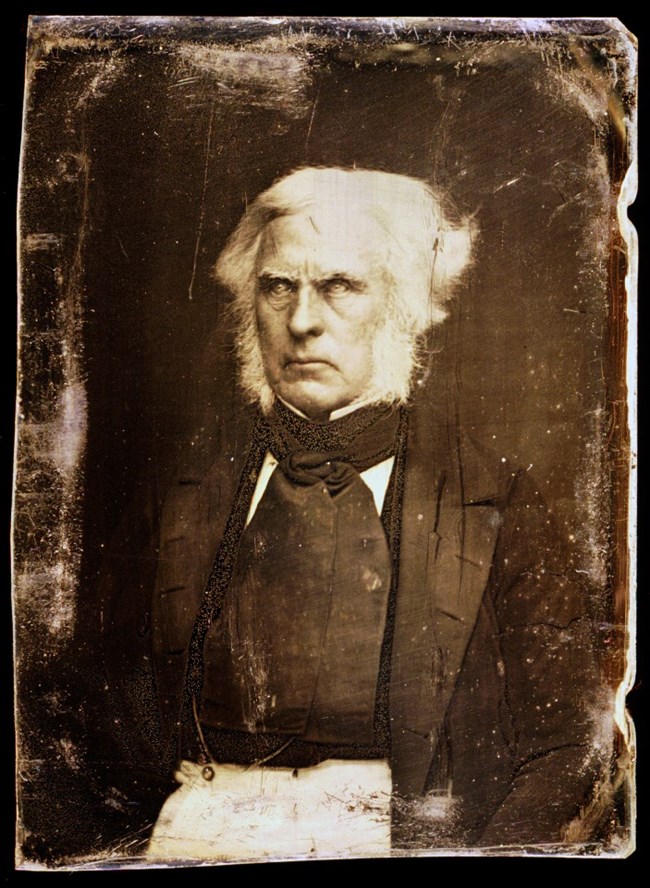

French Canadian voyageurs rowed bateaux and trapped fur-bearing animals for the Company. The French language would have been frequently heard in the fort's employee Village, and French was a component of Chinook Jargon, a common pidgin language used by Northwest traders. The Gallic roots of many of these employees were shared with many of the Company's officers, like Dr. John McLoughlin, Chief Factor of Fort Vancouver from 1825 to 1845. McLoughlin and his family were closely tied not just to French culture, but to France itself.

NPS Photo

McLoughlin was born in 1784 in Rivière-du-Loup, Québec. McLoughlin’s French heritage came from his mother, Angélique Fraser, who was the daughter of a French Canadian Catholic mother, Marie Allaire, and a Scotch Presbyterian father, Malcolm Fraser.

McLoughlin’s father, an Irish Catholic farmer also named John, was known by the French title cultivateur (though Angélique’s brother, Alexander, called the elder McLoughlin “the Bête” because of the elder McLoughlin’s illiteracy). Regardless of direct ancestry, French heritage, customs, and language were pervasive in the Québécois culture of eastern Canada.

At Fort Vancouver, Dr. McLoughlin’s French heritage continued to play a role. According to his daughter, Eloisa, he spoke with a “slightly French accent.” On Sundays, McLoughlin read the Bible in French to his French Canadian employees. It was the language of Catholicism at Fort Vancouver, largely because most of the fort’s Catholics were also French Canadian. In the 1840s, McLoughlin arranged for French Canadian priests François Norbert Blanchet and Modeste Demers to journey to the fort and minister to its population; the records they left behind are largely in French.

NPS Photo

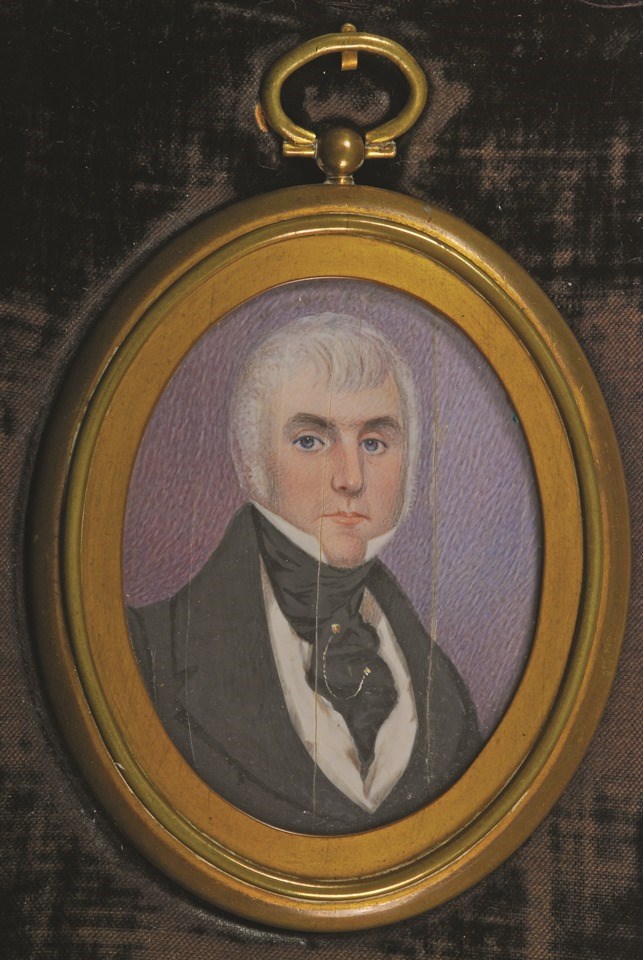

Dr. John McLoughlin’s brother, Dr. David McLoughlin, was also intimately connected with France. Trained as a doctor at the University of Edinburgh, David served as an Assistant Surgeon with the British Army during the Napoleonic Wars, and followed his unit across the Iberian Peninsula and into Southern France.

David, who was said to have borne a strong resemblance to his brother John, remained in France after the war. After the downfall of Napoleon Bonaparte’s French Republic in 1815, monarchy returned to France. With this change in government, accompanied by a period of relative political stability, France became a popular destination for British tourists. David’s fame as a physician hinged on this influx of British travelers and the lingering presence of the British military. In 1824 in Boulogne, France, David delivered the child of the wife of the Duke of Wellington’s personal secretary, who was, herself, a well-connected aristocrat. The case was a difficult one, and might have ended in the death of the child or mother were it not for David’s intervention. Word about his skill spread, and he became increasingly popular as a physician with a specialty in obstetrics.

David established a practice in Paris, and was living there during the French Revolution of 1830, which deposed the Bourbon monarchy and installed King Louis-Philippe, to whom David became a court physician.

NPS Photo

NPS Photo

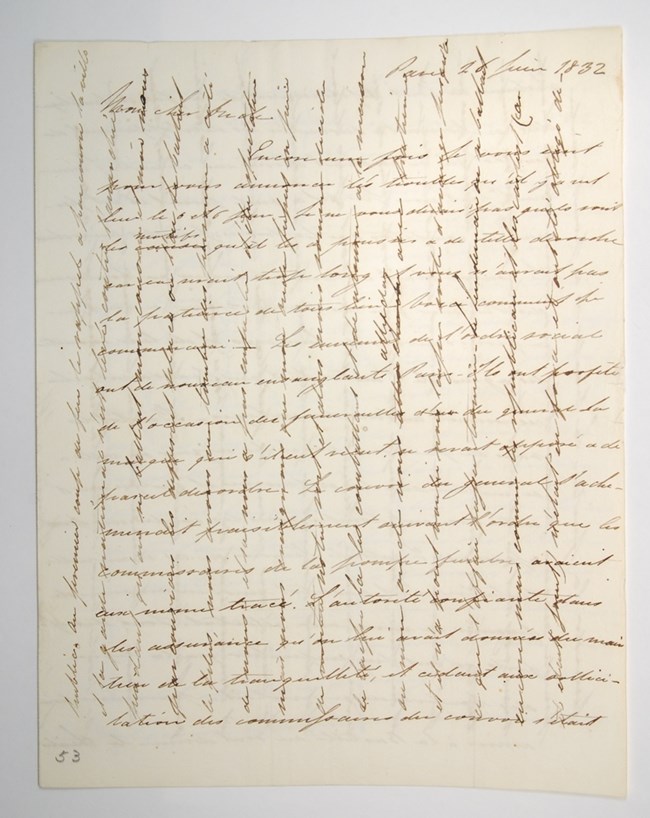

At the end of the letter, John sided strongly with the monarchy, against the revolutionaries, writing that the King’s troops should “shoot them all.” By 1833, however, John’s extravagant spending and a mysterious scandal caused David to send him back to North America.

Dr. John McLoughlin’s son David also spent time with his uncle in the 1830s. Dr. John McLoughlin himself spent the winter of 1838-1839 visiting his brother in Paris.

Paris at the time was a place of many contradictions. Louis-Philippe, called the “Citizen King,” tried to be a man of the people – making a habit of walking the streets of Paris and shaking hands with people from all walks of life (though he kept two pairs of gloves on hand – a “dirty” glove for shaking lower class hands and a clean glove for shaking upper class hands). But despite these attempts at populism, the city was still rocked by violence, thwarted revolutions, and several failed attempts on the king’s life.

In part due to decades of revolution and war, the French Industrial Revolution came slightly later than its English counterpart. While London had already developed a functional sewage system, open sewers could still be seen in Paris in the 1830s (the stench must have been jarring to Dr. John, who was, perhaps, more used to the fresher air of the sparsely populated Pacific Northwest). But the decades during which the McLoughlin family inhabited Paris were also times of great progress: gas lighting replaced the city’s old oil lamps, the railroad began to connect the city to the countryside, and the advent of Romanticism inspired a flowering of art and literature.

Dr. David McLoughlin was awarded the Legion d’Honneur in 1842 “by virtue of his service as an English doctor.” He also wrote numerous books on a variety of medical topics, including three on the topic of cholera, a disease he would have seen firsthand during Paris’ epidemic of 1832. 1840s censuses list his addresses in and around Paris’ Place Vendôme, a location in Paris’ upper-class 1st arrondissement.

By the late 1840s, David McLoughlin disappears from French censuses, and reappears in 1849 in London. This move coincides with the French Revolution of 1848, which deposed David’s employer, King Louis-Philippe. Like David, Louis-Philippe also escaped to England, where he lived out his retirement after his brief career as the last King of the French.

Dr. John McLoughlin and his sons lived out their days in the Pacific Northwest. John McLoughlin, Jr., joined the Hudson's Bay Company. In 1842, John, Jr., was left in charge of the Company's Fort Stikine and was murdered by the men under his command. Dr. John McLoughlin died in 1857 in his home in Oregon City, Oregon (now the McLoughlin House Unit of Fort Vancouver National Historic Site). Dr. David McLoughlin never returned to North America, and died in London in 1870. Though they stayed connected via a slow system of correspondence, the two brothers, who last saw each other in Paris in 1839, never met again.