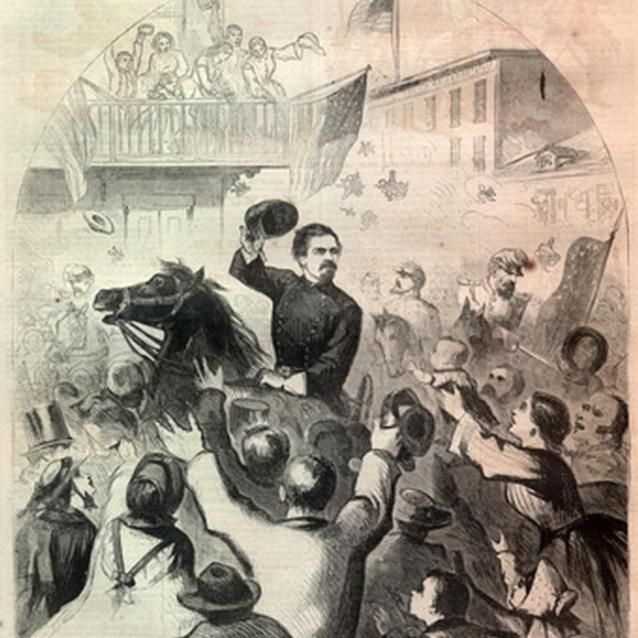

According to most records, McClellan and his men received a much warmer reception than the Confederates when they rode into Frederick on September 13th. Even greater than the cheers of the people, though, was an unexpected gift: the discovery of a copy of Special Orders 191. During the Union march to Frederick, a skirmish line of soldiers from Company F, 27th Indiana stumbled upon the orders on September 13th.

"Here is a paper with which, if I cannot whip Bobby Lee, I will be willing to go home" General George B. McClellan

Orders Found

Library of Congress

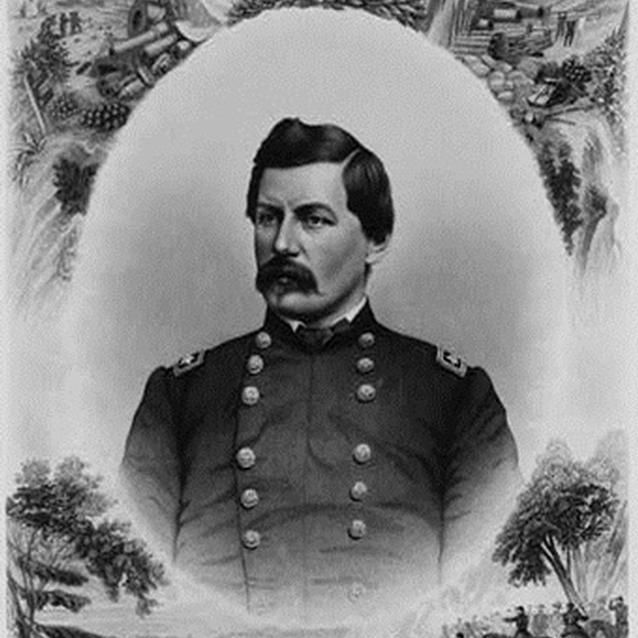

Sergeant John M. Bloss, commander of Company F's skirmish line when the orders were found, wrote a letter thirteen days later. In this unpublished letter, Bloss gives a few details about the finding of the orders. Bloss' letter and description is the primary source written closest to the time of the event, by far making it the most reliable information currently available about the facts surrounding the finding of the orders.

*Union General Samuel E. Pittman authenticated the orders by identifying Chilton's signature. Prior to the war Pittman had been a teller at Michigan State Bank in Detroit at the same time Chilton was the paymaster for the army stationed there. As paymaster Chilton kept an account at the bank and Pittman was familiar with his signature on checks and account records.

McClellan makes his own plans

Library of Congress

The finding of Special Orders 191 had a significant impact on the 1862 campaign. McClellan said that until the 13th, when he received the orders, he wasn't certain where Lee's army was going; Pennsylvania, Baltimore, Washington, or recrossing the Potomac, which is why he had three wings of the army spread out. The orders confirmed for McClellan that Lee was not trying to take Washington, but was in fact, headed west. At 3:00 p.m. on the 13th, McClellan sent the orders to his cavalry chief, Major General Alfred Pleasanton and told him to verify to what extent the orders, which was several days old, had been followed. In a 6:20 p.m. message to Major General W. B. Franklin, commanding the Sixth Corps, McClellan informed him about the finding of the orders, and let Franklin know that Pleasanton had skirmished in Middletown and occupied the town. Also, Burnside's command, including Hooker's Corps was marching that evening and early in the morning, followed by Sumner, Banks, and Sykes' division toward Boonsboro. McClellan wanted Franklin to move at daybreak by Jefferson and Burkettsville toward Rohrersville. His intention was to cut the Confederate army in two.

Lee mentioned that McClellan's sudden change in tactics after the Union army arrived in Frederick was unexpected. Upon learning about the lost copy he understood the change, saying, "to discover my whereabouts... and caused him to act as to force a battle on me before I was ready for it... I would have had all my troops reconcentrated... stragglers up, men rested and intended then to attack." In fact, Harpers Ferry took much longer to fall into Confederate hands than anticipated. This combined with the finding of the fateful document prompted McClellan to move his army quicker than the Confederates anticipated, undoubtedly contributing to Lee being forced into battles at South Mountain and Antietam, instead of waging a battle with his own timetable, location, and conditions.

Buying Time

Library of Congress

Based on his reading of Special Orders 191, McClellan developed a plan to send relief to Harpers Ferry, and then take the rest of the army, nearly 60,000 men, and cross South Mountain at Turner's Gap, descend to Boonsboro and interpose themselves between Lee's forces at Boonsboro and the rest of the Army of Northern Virginia.

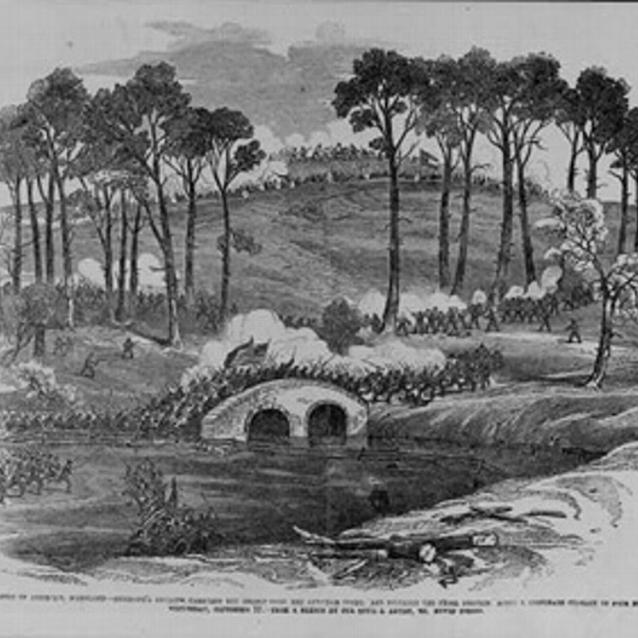

On the morning of the September 14th, advance elements of the Army of the Potomac attempting to clear Turner's Gap encountered part of D. H. Hill's division. A confusing and sharp action developed in the rough mountain terrain of South Mountain. Unable to hold their positions, the Confederates slowly withdrew. Five miles to the south, at Crampton's Gap, the Union Sixth Corps, on their way to relieve Harpers Ferry, overcame fierce resistance by a small Confederate force, and smashed their way through Crampton's Gap into Pleasant Valley on the west side. Union losses for the day were 2,346. The Confederates lost more than 4,100 men. That night, as Lee assessed the situation situation, he decided to withdraw by way of Sharpsburg and hoped Jackson would be successful in taking Harpers Ferry.

Lost Opportunities

Library of Congress

All day on September 15th, the Army of the Potomac poured over South Mountain and massed around Keedysville, Maryland. Lee watched and waited anxiously, his own army slowly reuniting around Sharpsburg. When McClellan did not attack on the 16th, Lee took strong positions along Antietam creek.

The Battle of Antietam commenced at first light on the 17th. Because McClellan fed his army into the battle piecemeal the battle developed into three distinct phases. All shared one common characteristic: horrible losses. It was the bloodiest and most shocking battle any of the combatants had yet seen.

By sunset, over 12,000 Union and 10,000 Confederates had been killed or wounded in twelve hours of fierce combat. The battlefield, wrote one Union officer, was "indescribably horrible." No other day in American history would surpass Antietam in carnage.

Part of a series of articles titled The Lost Orders.

Previous: Taking the Battle North

Tags

Last updated: February 3, 2015