Introduction

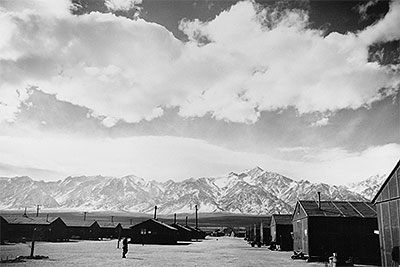

NPS/Ansel Adams

In 1942, the United States government ordered over 110,000 men, women, and children of Japanese ancestry to leave their homes in California and parts of Washington, Oregon, and Arizona. Under the guise of “military necessity,” the U.S. Army established 10 military-style camps to house the people in remote areas, under guard, for the duration of the war. One of the camps was at Manzanar, in the Owens Valley of eastern California. At Manzanar, more than 10,000 people spent up to three years behind barbed wire simply because of their ancestry.

The World War II exclusion of Japanese Americans lasted from 1942 to 1945. Nearly forty years later, the Commission on the Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians concluded: “Executive Order 9066 was not justified by military necessity…The broad historical causes that shaped these decisions were race prejudice, war hysteria and a failure of political leadership.”

At the heart of the experience lies the U.S Constitution and the rights and protections it promises all Americans. On March 3, 1992, Congress established Manzanar National Historic Site to preserve the history and educate the public.

Every person whose life was affected by that forced relocation has a story. At Manzanar National Historic Site, personal stories are shared through exhibits, a documentary film, and audio clips.

A Democracy at War

On Sunday, December 7, 1941, Mary Tsukamoto abruptly stopped practicing the piano for her church’s upcoming Christmas program when she heard the news: Japan had attacked the U.S. naval base in Hawaii. “The whole world turned dark,” she recalled. At the same time, Tom Kawaguchi left the public library in San Francisco as newsboys screamed, “Extra! Extra! Japs Bomb Pearl Harbor!”

On his way home, Tom feared that bystanders were “ready to pounce” on him. In the days that followed, all people of Japanese ancestry living in the U.S. came under suspicion. Many politicians, military leaders, and ordinary citizens believed they would side with their country of ancestry, Japan, rather than their country of birth, America. Mary Tsukamoto and Tom Kawaguchi were just two of nearly 112,000 Japanese Americans living on the west coast in 1941 whose lives would be forever altered.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt asked Congress to declare war on Japan the next day and on Germany and Italy three days later. On February 19, 1942, he signed Executive Order 9066, authorizing the U.S. military to carry out the exclusion and detention of American citizens and resident aliens. Although the order did not specify any ethnic group by name, in practice it applied to German and Italian aliens as individuals, but to all people of Japanese ancestry living on the west coast.

During the ten weeks between Pearl Harbor and the signing of Executive Order 9066, newspaper columnists and politicians debated whether to oust Japanese Americans from the west coast. Many were persuaded by Secretary of the Navy Frank Knox’s statement that “fifth column activity”—collaboration from within—explained Japan’s stunning success at Pearl Harbor. California Attorney General Earl Warren and other politicians claimed the proximity of Japanese-owned farms to airstrips, harbors, and rail lines was proof of intended sabotage, even though most of this acreage had been reclaimed from marginal land decades earlier. In mid-February 1942, all of California’s congressmen stated their unequivocal support for removal. Although some clergy and newspaper editors consistently voiced opposition, they could not alter the course set by Executive Order 9066.

Not all politicians and military leaders doubted the loyalty of Japanese Americans. FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover found no “factual data” to justify the mass relocation. Attorney General Francis Biddle believed this action clearly violated the U.S. Constitution. Nevertheless, the war department prevailed. Lt. General John L. DeWitt of the U.S. Army Western Defense Command, who infamously stated “The Japanese race is an enemy race,” imposed travel restrictions and curfews; ordered the confiscation of weapons, short-wave radios, and cameras; and ultimately directed the removal of all Japanese Americans from the west coast.

Living Behind Barbed Wire

NPS/Ansel Adams

Momo Nagano arrived at the Owens Valley Reception Center with her parents and younger brother on April 2, 1942. “I had envisioned Manzanar as a camp of little white cottages,” she recalled. “I can still vividly recall my dismay…as we pulled into Manzanar…and saw rows of black tar-papered barracks, some finished and others still being built, our home for an indeterminate future.”

The Owens Valley Reception Center became Manzanar War Relocation Center on June 1, 1942, and reached its peak population of 10,046 in September. “Camp life was highly regimented,” recalled Kinya Noguchi. “It was rushing to the wash basin to beat the other groups, rushing to mess hall for breakfast, lunch and dinner.”

Shiro Nomura remembered, “I awoke to the sharp clanging of bells…a large brake drum hung from the corner of each mess hall and the noisy clanging was the daily call to chow.” Three times a day, people in Manzanar lined up for meals served cafeteria-style. “Family meals soon became a forgotten practice for children ate with their playmates or tried different dining halls,” recalled Kazuyuki Yamamoto.

With food, housing, health care, and a clothing allowance provided by the War Relocation Authority, family life continued under altered conditions in camp. Room assignments kept families together, but often required them to live with strangers to achieve a total of eight per room. Privacy was scarce. Rosie Maruki Kakuuchi, a teenager at Manzanar, found using the latrines and showers with no partitions particularly “embarrassing, humiliating and degrading.”

Manzanar changed substantially between the day it opened in March 1942 and the day it closed in November 1945. Those incarcerated transformed the landscape with ponds and gardens. Families welcomed babies and mourned deaths. Schools educated students, internal security helped prevent crime, and the fire department extinguished fires. In its first anniversary issue, the Manzanar Free Press published an anonymous poem about the complexity of life at Manzanar:

“Out of smiles and curses, of tears and cries, forlorn; Mixed with broken laughter, forced because they must… Out on the desert’s bosom—a new town is born.”

More than 4,000 adults worked as clerks, chemists, accountants, nurses, doctors, teachers, fire fighters, repairmen, switchboard operators, and other occupations needed to maintain a “city” of 10,000. They earned from $12 to $19 per month on a wage scale set low to ensure they would not earn more than an Army private’s $21 monthly salary.

A Community Activities staff planned recreational activities at Manzanar, and Japanese Americans organized many more. Athletic programs and victory gardens developed in the firebreaks while dances, arts and crafts classes, and clubs met in recreation buildings and mess halls.

Many participated in religious activities and worship. The Buddhist Church, led by Rev. Shinjo Nagatomi, had the largest congregation. The Protestant Manzanar Christian Church and the Catholic St. Francis Xavier mission also were active in Manzanar.

Bringing Beauty to the Desert

NPS/Ansel Adams

Manzanar’s wood and tarpaper barracks were no match for Owens Valley’s wind, dust, and extreme temperatures. Congressman Leland Ford, visiting Manzanar in 1942, remarked, “On dusty days one might as well be outside.” In addition to dealing with crowded conditions and a lack of privacy, they also had to make do with the few belongings they brought with them. As Yuri Tateishi recalled, “What hurt most I think was seeing those hay mattresses … It was depressing, such a primitive feeling. We were given army blankets and army cots. Our family was large enough that we didn’t have to share our barrack with another family, but all seven of us were in one room.”

Within months, most acquired additional furnishings to make their barracks apartments more habitable. Some built furniture from scrap wood, while others ordered from catalogs or had their possessions shipped from warehouses. In 1942, the WRA supplied plasterboard and linoleum that Japanese American crews installed to seal floors and walls. The scarcity of goods made simple things precious. “To a friend who became engaged,” wrote Noriko Bridges, “we gave nails—many of them bent … snitched from our father’s meager supply or found by sifting through the sand in the windbreak.”

The transformation of the apartments mirrored changes occurring outside. Over four hundred landscape professionals came to Manzanar in 1942. In a matter of months, they transformed the bleak camp environment. Japanese Americans planted lawns, trees, and flowers near their barracks and created mess hall gardens to relieve the boredom of standing in line at mealtime. “It just gave you a good feeling. Even though we were confined, people cared about themselves and about their surroundings,” recalled Arthur Ogami.

In October 1942, the Manzanar Free Press observed, “Six months ago Manzanar was a barren uninhabited desert. Today, beautiful green lawns, picturesque gardens with miniature mountains, stone lanterns, bridges over ponds…attest to the Japanese people’s traditional love of nature.” Tsuyako Shimizu recalled, “When we entered camp it was a barren desert. When we left camp, it was a garden that had been built up without tools.”

Of Liberty and Loyalty

NPS/Ansel Adams

Three months after Manzanar opened, the U.S. victory at the Battle of Midway boosted America’s confidence in the war against Japan. By early 1943, a growing number of military leaders and WRA administrators believed that tens of thousands of loyal U.S. citizens should no longer be deprived of their liberty. As the Washington Post exclaimed, “American democracy and the Constitution of the United States are too vital to be ignored…the panic of Pearl Harbor is now past.”

Acting jointly, the War Department and the WRA implemented a program to distinguish the “loyal” from the “disloyal.” The War Department sought to clear Nisei for voluntary service in the armed forces, and the WRA hoped to pave the way for resettling out of the camps. However, the “loyalty questionnaires” they used, intended to rush the release, instead ushered in a period of chaos at all 10 camps.

By March 1944, the WRA had transferred 2,200 people from Manzanar to Tule Lake. People went for many different reasons. Some spouses, children, and siblings went along to keep their families together. Eldest sons usually felt obligated to help aging parents regain a foothold after the war, rather than risk their lives in battle. Some had property and relatives back in Japan to consider. Others simply weren’t ready or able to move to unfamiliar, potentially hostile places outside California.

Ben Takeshita recalled that the turmoil created by the loyalty questionnaires “left families torn apart, parents against children, brothers against sisters.” Reactions ranged from quiet compliance to overt resistance. As the government forced those they imprisoned to declare their “loyalty,” private sentiments about the camp experience suddenly became very public issues with profound consequences. Different choices led to different fates—jobs and colleges in the Midwest and east coast, military service in Europe, segregation at Tule Lake, or expatriation to Japan.

Fighting the Enemy While Fighting Prejudice

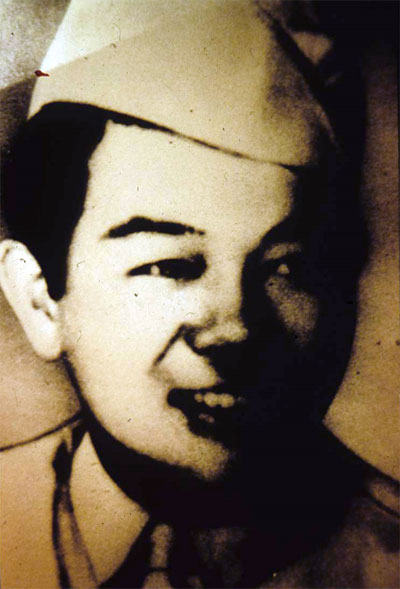

NPS

Approximately 4,000 Japanese American men and women went into military service directly from war relocation centers, including 2,800 who were drafted. In November 1942, Karl Yoneda left Manzanar with twelve others to join the Military Intelligence Service (MIS). A few months later, Burns Arikawa volunteered for the 442nd from Manzanar, joining his brothers Frank and James in the service. Together, they proved U.S. Army Air Force Sergeant Ben Kuroki’s words: “Under fire, a man’s ancestry, what he did before the war…don’t matter at all…whether you realize it at the time or not, you’re living and proving democracy.”

In July 1946, President Harry Truman greeted surviving members of the 100th/442nd at the White House. “You fought not only the enemy,” he said, “but you fought prejudice. And you’ve won.”

Four soldiers with family in Manzanar died during the war. One of them, Sadao Munemori, was the only Japanese American awarded the Medal of Honor during that era. Others would wait decades for such recognition.

Righting a Wrong

Although some protested these events by pursuing court cases, resisting the draft, or responding negatively to the loyalty questionnaire, the vast majority did not want to “make waves.” As they had during their years in camp, many relied on a spirit of shikata ga nai,—it cannot be helped—to rebuild their lives after the war.

In 1981, Michael Yoshii testified before the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians (CWRIC) that his family’s time in camp was difficult “to discuss with my parents…Their words said one thing, while their hearts were holding something else deep inside.” After listening to over 750 individual testimonies, the commission recommended that the U.S. government make monetary reparations and issue a formal letter of apology. Eight years later, the redress bill HR 442—numbered in honor of the 442nd Regimental Combat Team— became law.

A Place in History

NPS

Reflecting on his years as a young man at Manzanar, Shi Nomura recalled both “ghosts of a nightmarish past” and “happy memories.” The government could “corral our bodies, control our movements, but not our spirit,” he later wrote. Beginning with a visit to the site in the early 1970s, Shi collected stories, photographs, and artifacts from those who had been incarcerated to create a Manzanar exhibit at the Eastern California Museum.

Sue Kunitomi Embrey, once a Manzanar camouflage factory worker and Free Press reporter, returned for the first Manzanar Pilgrimage on a day of “bitter cold” in December 1969. In the decades that followed, she spearheaded a grassroots effort to achieve state and federal recognition of the site. “No one could really learn from the books,” she later said. “You have to walk through the blocks, see the gardens, and the remains of the stone walls and rocks.”

Today, the National Park Service continues the work of Sue, Shi, and others by preserving the landscape and stories of Manzanar.

Last updated: November 20, 2015