Last updated: June 10, 2024

Article

California: Manzanar National Historic Site

Courtesy of the National Park Service

In March 1942, after the US Army leased 6,200 acres at Manzanar from the City of Los Angeles, the evacuation of the first group of Japanese Americans began. With little notice, the US Army informed the people of Japanese ancestry to gather their belongings and decide what to do with their homes, businesses, and other possessions. As Manzanar internee William Hohri recalled, “We had about one week to dispose of what we owned, except what we could pack and carry for our departure by bus.” Everything else they either sold or left with friends and religious groups. Those who were unable to sell or rent their homes had to abandon their properties and hope for a quick return, but they were not released until the end of the war.

By August, the relocation of Japanese Americans to all camps was complete. The government sent 10,000 of the 120,000 internees to Manzanar to live. Hastily built by the first group of internees to arrive at Manzanar, the relocation center was a 640-acre rectangular lot surrounded by barbed wire and eight guard towers. Today, the fence and towers are no longer standing, but the line where the fence once stood is still visible. On 5,560 acres outside the fence, the army built housing for the military police, a reservoir, a sewage treatment plant, agricultural fields, and a cemetery. Only the cemetery, a few sentry posts, and part of the water reservoir remain.

Within the barbed wire fence, the camp consisted of 504 barracks organized into 36 blocks. Each of the blocks had a main building housing the camp’s communal bathrooms, laundry rooms, and mess halls. About 200 to 400 people resided in each block, and were usually crowded into 14 barracks. Each barrack had four rooms and was furnished with a stove, a hanging light bulb, blankets, and a few straw mattresses. Only a few concrete walls and poles that supported these buildings remain. Still visible at the northwest area of the camp’s main entrance is a large metal building that served as the school auditorium. At the main gate of the camp are two stone structures that the internees built with hints of Asian architecture.

The Asian design of the stone structures was not the only aspect of Japanese culture the internees incorporated in Manzanar. Despite living in crowded barracks, the internees worked together to make the best of a bad situation. With the assistance of the War Relocation Authority, which formed a council of internee-elected block supervisors, the Japanese Americans at Manzanar were able to build churches, form girls and boys clubs, and participate in a variety of recreational activities. They played sports and music, danced, planted gardens, and published The Manzanar Free Press. Manzanar functioned like any town, with internees working daily in a variety of professions. At the camp, many worked as doctors, nurses, police officers, firefighters, and teachers. They also raised chickens, built furniture, and made clothing for their community and camouflage for the army.

Although people of Japanese ancestry living in the United States could not serve in the US Army at the beginning of the war, many of the internees at Manzanar helped with the war effort to prove their loyalty to the United States. In addition to making camouflage nets, after Japan cut off America’s rubber supply, the resident scientists at Manzanar began working on finding alternative sources of rubber. Under the guidance of Dr. Robert Emerson, they experimented with guayule and were able to extract rubber from the woody components of this desert plant successfully. This was one of many jobs the Japanese internees performed to support the war effort and eventually they were able to fully demonstrate their patriotism when the Army reinstated the draft of Japanese Americans.

At the end of the war, nearly 26,000 Japanese Americans from all camps had served in the US armed forces. Of those who enlisted, 9,486 died fighting for the American forces. In 2010, 65 years after the war ended, President Barrack H. Obama awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor to the brave Japanese Americans who served in World War II. When the war was over, the United States government ordered all camps closed, and in November 1945, the last group of internees left Manzanar. Today one of the best preserved of the War Relocation Centers, Manzanar National Historic Site provides great insight into the experience of Japanese Americans during World War II.

At the site, visitors can begin their tour at the restored auditorium, where the Manzanar Interpretive Center and bookstore are located. Here 8000 square feet of exhibits tell the history of Manzanar and the stories of all peoples of Japanese heritage interned at the camp. Visitors can learn about the highlights of Manzanar’s history before the war that include stories of the Owens Valley Paiute Indians; miners and homesteaders from Scotland, France, Mexico and Chile; and the Apple Orchard Community for which the area of Manzanar (Spanish for apple orchard) is named.

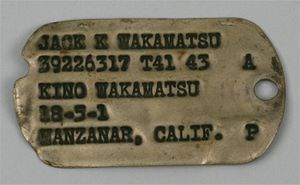

The exhibits include photographs, artifacts, and a large-scale model of the Manzanar War Relocation Center as it looked during the time when Japanese Americans resided at the camp. A list of the names of the 10,000 Japanese Americans interned at Manzanar during World War II is also at the site. Visitors are encouraged to watch the award winning film, “Remembering Manzanar,” which runs every half hour. At the Interpretive Center and bookstore, visitors can obtain a brochure and stamp their passports to begin their journey into the history of Manzanar.

Beyond the Interpretive Center, visitors may take a 3.2-mile self-guided auto tour past the sentry posts, portions of the water system, cemetery, and the ruins of the administrative complex. On foot, visitors can tour through the gardens in block 22, the chicken ranch, orchards, and other structures not visible on the main auto tour road.

Manzanar National Historic Site, a unit of the National Park System and a National Historic Landmark, is located 9 miles north of Lone Pine, CA and 6 miles south of Independence, CA on the west side of U.S Highway 395. Click here for the National Register of Historic Places file: text and photos. The park grounds are open daily from dawn until dusk. The Interpretive Center is open from 9:00am to 5:30pm in the summer (April – October), and from 9:00am to 4:30pm during the winter (November – March). Manzanar National Historic Site is closed on Christmas Day. There is no admission fee. For more information, visit the National Park Service Manzanar National Historic Site website or call 760-878-2194.