In May 2003, Saguaro National Park sponsored a “pulse study” of the Madrona Ranger Station area in the park’s Rincon Mountain (east) District. While the definitions of pulse studies vary, their main goal is to bring together scientists and land managers to quickly assess the ecological health of an area. Pulse studies have been successful in many forests and parks, including Olympic and Sequoia/King’s Canyon national parks.

Introduction

NPS

The Madrona Ranger Station area (hereafter called “Madrona”) is a lush desert oasis far from the park’s popular cactus forest and includes a series of perennial pools in Chimenea Creek. For many years it was a base camp for the park’s backcountry operation, but the deteriorating facility was abandoned around 1999. Public access is limited, but potential changes in management and visitor use, and rapid development outside park boundaries, had raised concerns about the site’s future.

The Madrona pulse study—2003

Saguaro National Park’s Madrona pulse study took place during a warm week in May 2003. Scientists from many disciplines and organizations participated, including biologists, ecologists, geologists, social scientists, cultural resource specialists and NPS resource managers. The Western National Parks Association and Friends of Saguaro National Park provided funding, with additional support from the Community Foundation of Southern Arizona and Earth Friends Wildlife Fund.

As in all pulse studies, scientists and managers at Madrona worked side-by-side all week in the field. Days began at dawn with bird surveys, and mornings were spent on animal and plant surveys, water quality measurements, sampling for aquatic invertebrates, and studying buildings and trails. At night, participants searched for frogs and checked mist nets for bats. Participants camped, studied, and learned together throughout the cool evenings and unseasonably hot days. The last two days included an outdoor workshop with additional park staff, friends' group members, and others that summarized results and included opportunities to work in the field with scientists and share information about Madrona’s history and resources.

Scientists concluded that Madrona was rich in ecological and cultural resources. More than 50 species of birds and 153 plants were observed during the short study. The pools, fed by bedrock springs in a unique geological setting, appear to be one the least impacted aquatic resources of their kind in the Tucson area due to low levels of historic diversions and recreation, and contain a stable population of the protected lowland leopard frog (Rana yavapaiensis). The results were written up in a technical report (Edwards and Swann 2003).

Follow up to the pulse study, 2003-2008

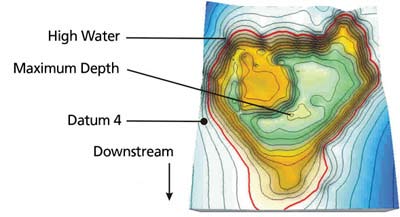

Participants in the Madrona pulse study left the park with many unanswered questions, including: What were the dynamics of water volume and water quality in the pools? How many visitors used the site? How was wildlife activity changing over time? How large was the threat from exotic species? The technical report identified a series of data gaps and recommended further research and monitoring. In the years since, the park has followed up with studies and monitoring that address some of these gaps, including regular monitoring of water levels in Chimenea Creek by volunteers; tracking of sediment levels in the Madrona pools and throughout the park; and studies of water quality. A graduate-student project examined the relationship between recreational use and water quality, and the USGS has begun baseline monitoring of heavy metals and other water-quality parameters.

Researchers also studied Sonora mud turtles (Kinosternon sonoriense) and amphibians, confirming the importance of the Madrona pools for aquatic species. During a drought in 2005–2006, leopard frogs and canyon treefrogs (Hyla arenicolor) disappeared, and many turtles died in a nearby stream when it went completely dry for nearly a year; however, most frogs and turtles survived at Madrona. We also used infrared-triggered “camera traps” to monitor mammals. During six years of surveillance, 20 species of medium and large mammal species were detected, including species of management interest such as mountain lion (Puma concolor) and white-nosed coati (Nasua narica).

NPS

In 2004 and 2005, Saguaro National Park received two grants from the Department of the Interior’s Cooperative Conservation Initiative. Working with the non-profit Rincon Institute, neighbors, and volunteers, we monitored visitor activity and restored several social trails and the abandoned stable area by seeding and planting native flowers, shrubs, and trees. We also removed non-natives plants, such as tamarisk (Tamarix ramosissima), and buffelgrass (Pennisetum ciliare).

Management implications

A major driver of the pulse study was the need for information for the park’s general management plan. The problem was how to appropriately manage and plan for a sensitive resource site that also included management activities. Alternatives in the plan recognize the educational and scientific value of Madrona. The approved plan calls for visitor use to be regulated, and facilities placed carefully, to protect sensitive resources. The study also noted that Madrona would become a primary destination if new trails ran through the area as proposed, and that heavy recreational use would adversely affect natural and cultural values. As a result, the trails plan calls for the Arizona Trail to connect to the Manning Camp Trail through a scenic area west of the site rather than through Madrona itself.

The Madrona pulse study benefited Saguaro National Park in unexpected ways. For example, more detailed information from this one site supported a partnership to create refugia for leopard frogs in backyard ponds outside the park. The study also renewed appreciation for the park’s history and the cultural values of wilderness. It was a factor in reinvigorating Saguaro National Park’s packing program and the 2005 celebration of Manning Cabin’s 100th anniversary, which brought back many old-timers who had lived, worked, and packed in the park’s wilderness areas.

Saguaro National Park’s Madrona pulse study provides evidence that pulse studies are a very useful, though underutilized, tool for connecting science and park management. The National Park Service Omnibus Management Act of 1998 directed the Service to integrate scientific knowledge into management decisions. Pulse studies seem to be ideally suited for site-specific resource issues that demand information in a short time frame but are complex enough to require a range of expertise. For Saguaro National Park, the Madrona pulse study also led to further monitoring and unexpected benefits.

Literature cited

Swann, D. E., M. Weesner, L. Norris, and S. Craighead. 2009. Pulse study links scientists and managers: An example from southern Arizona. Park Science 26:64-69.

Project contact

Don Swann

Saguaro National Park

3693 South Old Spanish Trail, Tucson, Arizona. 85730

e-mail us

Prepared by Saguaro National Park, 2010.

Last updated: February 3, 2015