Part of a series of articles titled Lowell, Story of an Industrial City.

Article

Lowell, Story of an Industrial City: The Industrial Revolution in England

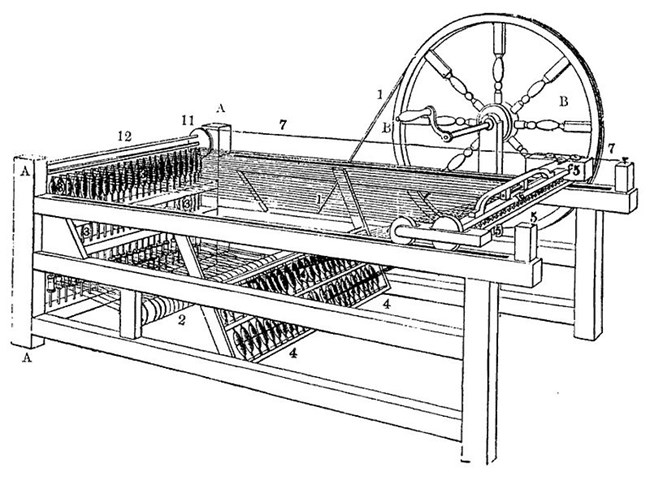

From Andrew Ure, Peter Lund Simmonds, and H.G. Bohn, 1861, The Cotton Manufacture of Great Britain Investigated and Illustrated. Public Domain (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Havgreaves%27_Spinning_Jenny.jpg)

The manufacture and export of various cloths were vital to the English economy in the 17th and early 18th centuries. Before the Industrial Revolution, textiles were produced under the putting-out system, in which merchant clothiers had their work done in the homes of artisans or farming families. Production was limited by reliance on the spinning wheel and the hand loom; increases in output required more hand workers at each stage.

Invention dramatically changed the nature of textile work. The flying shuttle, patented by John Kay in 1733, increased the output of each weaver and led to increased demand for yarn. This prompted efforts by others to mechanize the spinning of yarn. The first advance came in 1767, when James Hargreaves invented the spinning jenny, allowing one spinner to produce several yarns at a time. Two years later Richard Arkwright patented the water frame, a spinning machine that produced a coarse, twisted yarn and could be powered by water. Coupled with the carding machine, the Arkwright spinning frame ushered in the modern factory.

The first textile mills, needing waterpower to drive their machinery, were built on fast-moving streams in rural England. After the 1780s, with the application of steam power, mills also grew up in urban centers. Initially, English mills relied on pauper labor, and for a considerable period mill owners had difficulty recruiting workers. Once in the mills, though, workers felt threatened bythe introduction of new machinery, and periodically resisted such moves by destroying power looms and setting fire to new factories. Nevertheless, the textile industry expanded rapidly, increasing production fifty-fold between 1780 and 1840.

The English Industrial Revolution had important consequences for Americans. It spurred cultivation of cotton in the South to meet expanding English demand for the fiber. The growth and profits of English textiles also caught the imagination of American merchants, the more farsighted of whom sought to manufacture cloth and not simply market English imports. But the degraded conditions and social unrest in English mill towns made many Americans wary of manufacturing. The formidable challenge was to import the innovations without bringing social ills with them.

---

From: Dublin, Thomas. 1992. Lowell: the story of an industrial city: a guide to Lowell National Historical Park and Lowell Heritage State Park, Lowell, Massachusetts. Washington, D.C.: Division of Publications, National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior.

Last updated: June 15, 2018