Last updated: March 15, 2024

Article

Lost, Tossed, and Found

Clues to African- American Life at Manassas National Battlefield Park

NPS

Using photographs, illustrations, and maps, this exhibit focuses on the African-American experience, in slavery and freedom, in the immediate vicinity of Manassas National Battlefield Park. Archeological survey and excavations at the battlefield resulted in the discovery of structural remains and a diversity of artifacts associated with nineteenth-century African-American life. The architectural features range from communal, antebellum-slave quarters (Brownsville) to post-Civil War single family houses (the Nash Site). Artifacts include an African heirloom – a carved, ebony finger ring – ceramic gaming pieces used in the African-derived game of Mancala, hand-built, low-fired earthenware bowls used and, perhaps, made by African-Americans, blue glass beads worn or sewn on clothing to protect the wearer against "the evil eye," and quartz crystals possibly used to predict the future or in curing rites. Analysis of the architectural features and artifacts provides new insights into the adaptation of African slaves to their New World environment and to the survival of African-inspired customs and traditions in the post-Civil War period.

Information and objects from the National Park Service archeological investigations have contributed directly to recent scholarly research and public interpretation, such as the Museum of the Confederacy's special exhibit "Before Freedom Came: African-American Life in the Antebellum South," the accompanying book of the same title published jointly by the Museum of the Confederacy and the University Press of Virginia, and a special exhibit titled "Pitchers, Pots & Pipkins: Clues to Plantation Life," sponsored by the Smithsonian Institution.

Portici

NPS

Plantation size was often measured by the number of slaves owned. With an average of 20 slaves, Portici was a "middling plantation" that evolved from an earlier farm, Pohoke, about 1820.

NPS

Destroyed by fire in 1863, only Portici's foundation remains. Archeologists found evidence of domestic servant quarters in cellar excavations. Unearthed from Portici, the carved finger ring of ebony (center) likely came from Africa with its owner, while rings of domestic horn (left) or bone (right) were fashioned here by African-Americans.

NPS

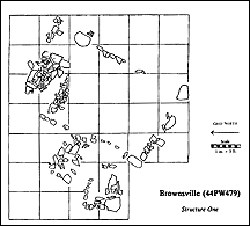

Brownsville

NPS

Archeological evidence suggests "Structure 1" at Brownsville, another middling plantation, served as a multi-family slave quarters.

NPS

NPS

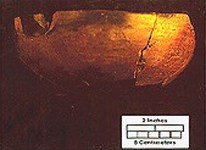

African-American Colonoware

NPS

Fragments of hand-made, unglazed earthenware bowls found at excavated antebellum sites are believed to have been made by slave artisans.

NPS

Glass Beads and Gaming Pieces

NPS

Excavation at slave's quarters yielded various objects used for entertainment. Among them are these edge-worn, geometrically shaped ceramics (bottom), pebbles (middle), and bone (top) markers, believed to be associated with Mancala, a game originating in Africa.

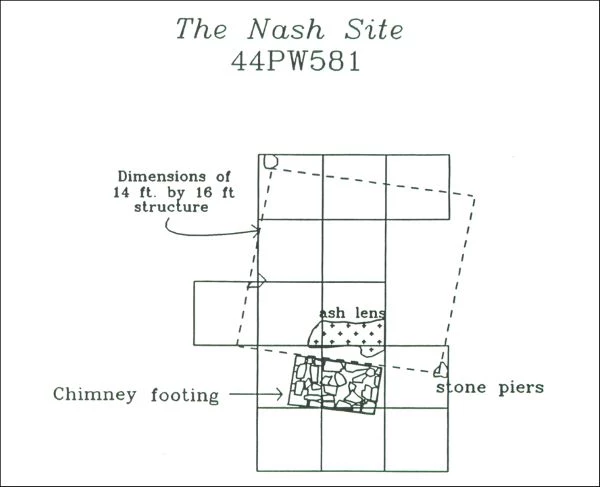

The Nash Site

NPS

At this post-war, single-family cabin site archeologists confirmed African-American occupation and a continuity of cultural traditions upon discovery of a blue bead and mancala gaming pieces.

NPS

NPS

Quartz crystals, a prehistoric quartz point, and a galena fragment (to the left of the dart point) were found clustered near the chimney footing. These invite speculation of a collective purpose such as a conjuring ritual.

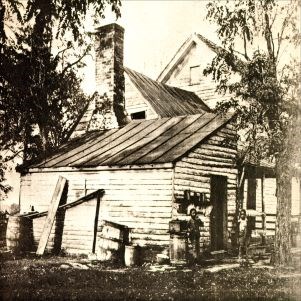

Robinson House

NPS

Mr. James "Gentleman Jim" Robinson, an educated freedman, prospered on his small farm, enabling him to buy the freedom of his wife and daughters. Additions to the house and family appear in this post-1888 view. Unlike his neighbors, Robinson proved his loyalty to the Union and received compensation for war claims.