Part of a series of articles titled Park Paleontology News—Vol. 17, No. 2, Fall 2025.

Article

Lost, then Found…then Lost Again?: The Importance of Fossil Locality Documentation in National Parks

Fossils are amazing. It’s a simple fact that most of us come to know as children, and one that some of us continue to consider truth as adults. Though thousands of people can agree on this one certainty, there are a multitude of reasons as to just why fossils fascinate us so. Some people enjoy the unique shapes and beauty of fossils like shark teeth, trilobites, and ammonites, often including them in jewelry. Others find significance in fossils for their appearance in the myths and legends of cultures both past and present. Still others enjoy the burst of excitement that comes from discovering a new fossil. I personally love fossils because each one, big or small, is a gift: a key to unlocking my understanding of a mysterious Earth that existed long before I did. They can tell us about ancient species that evolved into the ones we see today, help uncover environmental conditions unlike any we’ve experienced, and paint a picture of entire ecosystems the likes of which we’ll never see again.

Alexandra Apgar, University of New Mexico

However, although fossils make for excellent clues, they are also rare ones. Fossils only form under incredibly special circumstances, and even within those cases, there may be other biases at play (i.e., only organisms with hard parts are likely to be preserved). Furthermore, the odds of humans finding them before erosion destroys them over time are similarly low (NPS: How Fossils Form, 2024). In fact, one recent study suggests that some vertebrate fossils, like individual backbones, may only survive for ten years once exposed before being lost to weathering (Sullivan and Keenan, 2022). The chances of a fossil being preserved, discovered, collected, and studied are incredibly small—so much so that each one may seem a miracle in and of itself. Fossils are our best method for investigating organisms, environments, and even entire ecosystems lost to time. Even if a fossil is successfully found and collected prior to erosion, it’s still alarmingly easy to lose them a second time.

Alexandra Apgar, University of New Mexico

There are quite a few circumstances within which a found or exposed fossil can disappear. Natural disasters like floods and wildfires can rapidly expose fossils that may have remained buried for much longer otherwise, but they may also destroy these fossils at a faster rate than they can be recovered. Fires may also demolish collected fossils within natural history collections, as seen in the devastating loss of specimens within the National Museum of Brazil in 2018 (BBC News, 2018). Collected fossils may also fall under siege, seizure, or destruction during wartime. One of the most infamous example of this rests with the ruination of the type specimen of Spinosaurus aegyptiacus—meaning the fossil that the entire species was described from—during an Allied bombing of Munich in 1944. Perhaps the most common form of fossil disappearance, however, is not the destruction of the physical fossil itself, but the loss of the information that makes them invaluable to science.

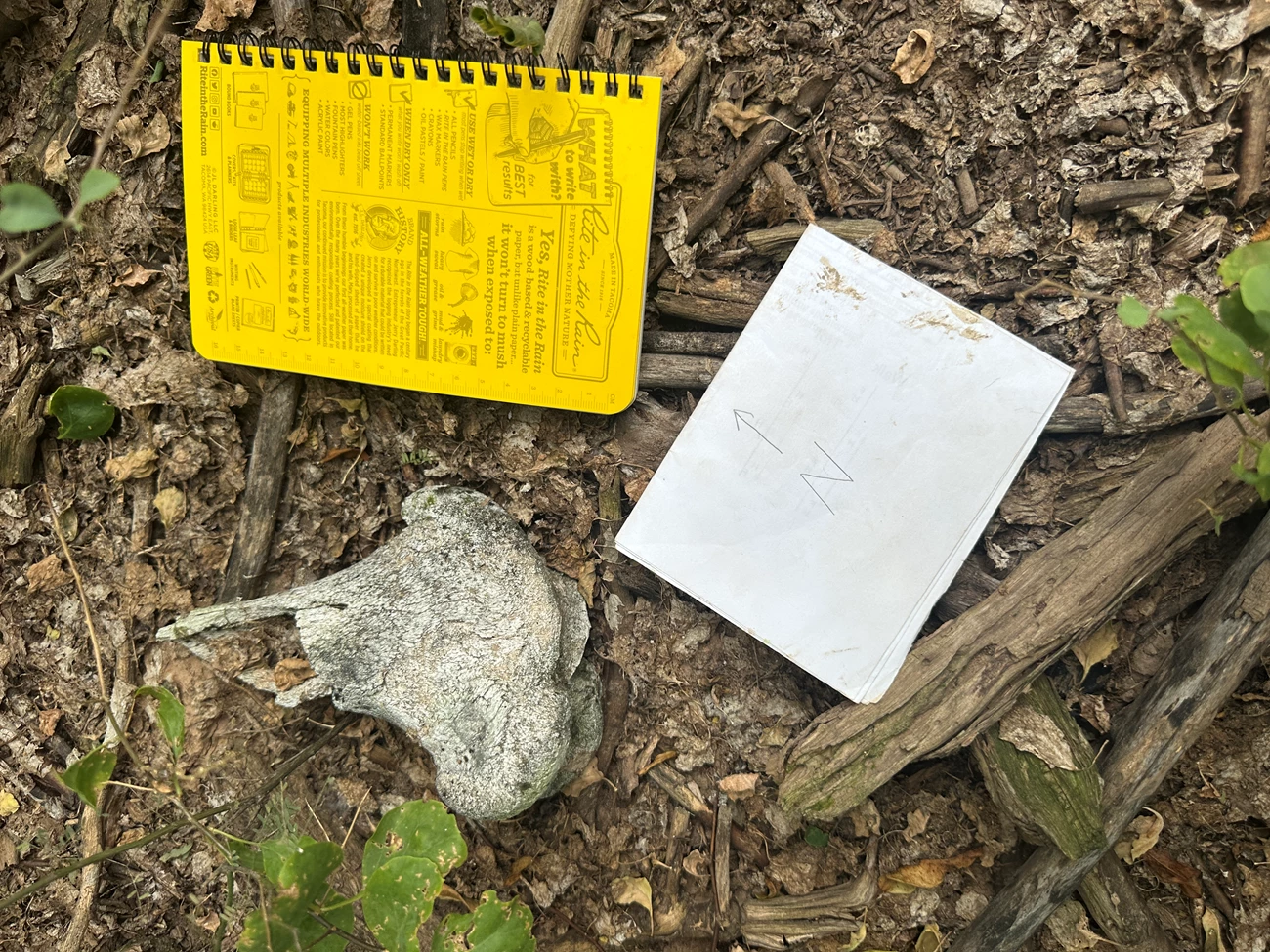

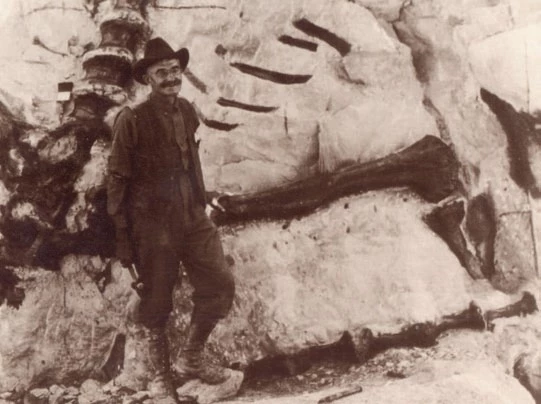

Imagine a single fossilized tooth. Using this one specimen, you may be able to figure out what organism it might be from or what it might have eaten. But what role did this organism play in its ecosystem? What kind of environment did it inhabit? How many millions of years has it been since it was alive? These kinds of questions can only be answered with geologic context from its fossil locality. Before a fossil is taken out of the ground, researchers must note aspects about the locality it came from, such as rock type, position and orientation of the fossil, association with any other fossils, etc. This information, when properly documented, creates the “story” that accompanies the fossil and allows scientific connections to be made. If this locality information disappears, its fossil is essentially lost to science – no accurate research investigations can be conducted without it. Furthermore, fossils frequently occur in concentrations, meaning that the same locality that produced one fossil may produce many more. Some localities can continue to produce fossils for decades. For example, dinosaur fossils were first discovered in Dinosaur National Monument in 1909, and Jurassic dinosaurs like Diplodocus and Allosaurus are still found there to this day (NPS: Earl Douglass, 2015). Being able to revisit a locality where fossils have been found may result in even more fossils being discovered before erosion can destroy them. Gathering accurate and precise details about where fossils were found, therefore, is paramount to providing important scientific context, ensuring the locality can be found again later in time, and providing data for monitoring of the site’s condition in the future.

Imagine a single fossilized tooth. Using this one specimen, you may be able to figure out what organism it might be from or what it might have eaten. But what role did this organism play in its ecosystem? What kind of environment did it inhabit? How many millions of years has it been since it was alive? These kinds of questions can only be answered with geologic context from its fossil locality. Before a fossil is taken out of the ground, researchers must note aspects about the locality it came from, such as rock type, position and orientation of the fossil, association with any other fossils, etc. This information, when properly documented, creates the “story” that accompanies the fossil and allows scientific connections to be made. If this locality information disappears, its fossil is essentially lost to science – no accurate research investigations can be conducted without it. Furthermore, fossils frequently occur in concentrations, meaning that the same locality that produced one fossil may produce many more. Some localities can continue to produce fossils for decades. For example, dinosaur fossils were first discovered in Dinosaur National Monument in 1909, and Jurassic dinosaurs like Diplodocus and Allosaurus are still found there to this day (NPS: Earl Douglass, 2015). Being able to revisit a locality where fossils have been found may result in even more fossils being discovered before erosion can destroy them. Gathering accurate and precise details about where fossils were found, therefore, is paramount to providing important scientific context, ensuring the locality can be found again later in time, and providing data for monitoring of the site’s condition in the future.

Special Collections Dept. of the J. Willard Marriott Library, University of Utah.

But this information, just like the fossils themselves, can also be at risk of disappearing. It can be especially easy for locality context to be lost for historic fossil sites that were discovered before the widespread use of GPS, making relocating the area much more difficult. Many historic fossil localities now lie within the protection of the National Park Service (NPS), whose history with paleontology dates back far before its founding in 1916 (Santucci, 2023). Currently, fossils have been identified in 288 NPS service areas. Eighteen of them have fossil resources specifically mentioned in their proclamation and/or enabling legislation. Thus, NPS units that preserve these valuable fossils have an even greater responsibility towards protecting them from disappearing, especially with regards to lost locality context.

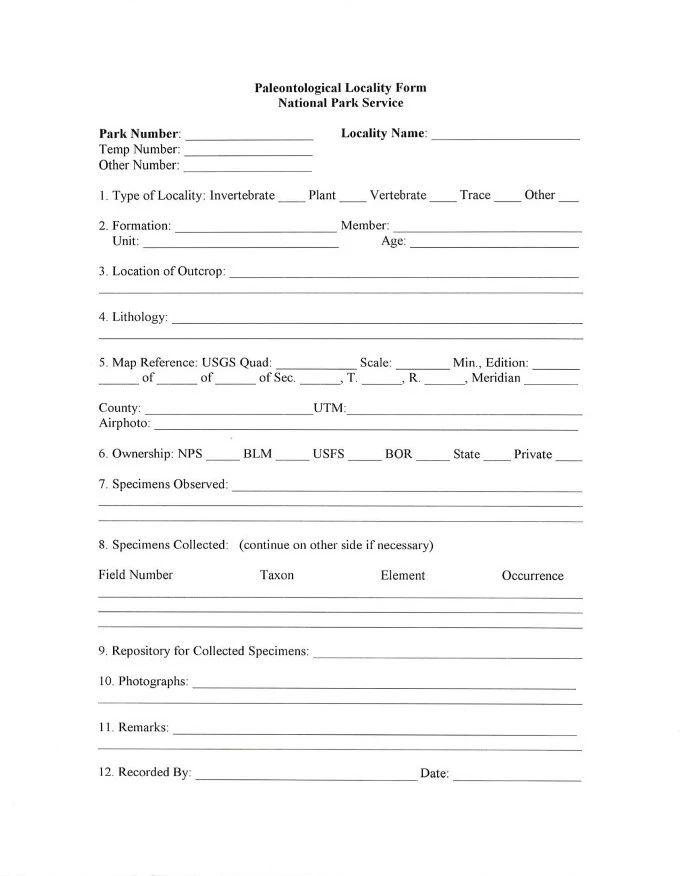

Scientists on staff within the NPS were quick to recognize the importance of proper fossil locality documentation. Additionally, for consistent record-keeping and large-scale scientific investigations to be done across multiple NPS areas, the locality data collected at each one would need to be consistent. To help staff in multiple NPS units gather all necessary data from newly discovered fossil localities, as well as provide updates on historical localities, two forms were created: the Paleontological Locality Form and the Paleontological Locality Condition Evaluation Form.

The Paleontological Locality Form condenses a wide variety of data types into a single sheet of paper. Spaces for the fossil locality’s name and official number within each park’s specific records are provided. The type or types of fossil present at the site (vertebrate, invertebrate, plant, trace fossil, etc.) are also noted. Stratigraphic information—that is, details relating to the type of rock preserving the fossils, its age, etc.—is documented alongside the location of the outcrop. Typically, this is recorded through GPS coordinates, then plotted on a physical map in order to create both a physical and digital record of the exposure’s exact placement in the area. It is also important to determine who owns the land the locality lies within. Usually the locality belongs to the National Park Service, but another federal agency (U.S. Forest Service, Bureau of Land Management, etc.) or even a private owner may be involved. Along with identifying collected specimens and documenting where they were stored, recorders must do the same for all photographs taken at the locality. It is vital to take multiple photos during each visit of the locality, because landmarks can be incredibly helpful for relocating a site. A space is also set aside for the recorder to sign their name and date. That way, if any locality context does become lost, there is a point of contact to aid in recovery.

Scientists on staff within the NPS were quick to recognize the importance of proper fossil locality documentation. Additionally, for consistent record-keeping and large-scale scientific investigations to be done across multiple NPS areas, the locality data collected at each one would need to be consistent. To help staff in multiple NPS units gather all necessary data from newly discovered fossil localities, as well as provide updates on historical localities, two forms were created: the Paleontological Locality Form and the Paleontological Locality Condition Evaluation Form.

The Paleontological Locality Form condenses a wide variety of data types into a single sheet of paper. Spaces for the fossil locality’s name and official number within each park’s specific records are provided. The type or types of fossil present at the site (vertebrate, invertebrate, plant, trace fossil, etc.) are also noted. Stratigraphic information—that is, details relating to the type of rock preserving the fossils, its age, etc.—is documented alongside the location of the outcrop. Typically, this is recorded through GPS coordinates, then plotted on a physical map in order to create both a physical and digital record of the exposure’s exact placement in the area. It is also important to determine who owns the land the locality lies within. Usually the locality belongs to the National Park Service, but another federal agency (U.S. Forest Service, Bureau of Land Management, etc.) or even a private owner may be involved. Along with identifying collected specimens and documenting where they were stored, recorders must do the same for all photographs taken at the locality. It is vital to take multiple photos during each visit of the locality, because landmarks can be incredibly helpful for relocating a site. A space is also set aside for the recorder to sign their name and date. That way, if any locality context does become lost, there is a point of contact to aid in recovery.

NPS Paleo Program

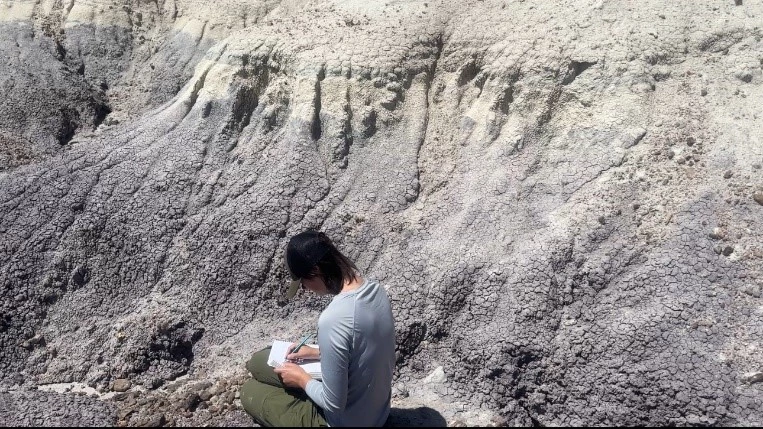

The accompanying Paleontological Locality Condition Evaluation Form is intended to be filled out during each visit to a fossil locality, in order to keep track of changes to the site such as sensitivity to erosion (fragility), fossil abundance and loss, site accessibility, and any human-made disturbances. Altogether, this information can help determine if any immediate action is needed. For example, if a locality is documented to have high fragility, that indicates to park staff that fossils are regularly eroding out of the rock at that locality naturally. This means that occasional visits to the locality to collect exposed fossils may be advisable to ensure no loss of important fossil data. However, if on the next visit the locality was documented to have moderate fragility, that would mean fossils were being exposed over the course of a few years, rather than with regularity each season. This would suggest less frequent collection.

Although these forms are designed to encompass all data that should be recorded for each and every fossil locality, they may look a little different from service area to service area. Some parks even have their own specific locality forms unique to them. Still others utilize digital records tablets to record their data over physical forms. No matter what wording, order, or format is used, however, the required data fields remain the same.

Although these forms are designed to encompass all data that should be recorded for each and every fossil locality, they may look a little different from service area to service area. Some parks even have their own specific locality forms unique to them. Still others utilize digital records tablets to record their data over physical forms. No matter what wording, order, or format is used, however, the required data fields remain the same.

Alexandra Apgar, University of New Mexico

The National Park Service, in its dedication to the public, also maintains a strong responsibility towards detailed and accurate scientific documentation. Thanks to these tremendous efforts, both historic and brand new fossil localities such as those within John Day Fossil Beds National Monument, Mammoth Cave National Park, Dinosaur National Monument, and more can be utilized for ground-breaking scientific research. My own investigations within Petrified Forest National Park require revisiting close to one hundred historically fossiliferous localities to gather data on the preservation styles of fossil bones in each one. Without the thorough documentation of fossil localities by previous and present park staff, I wouldn’t be able to find any of them, and the secrets behind large-scale preservation patterns of fossils would still remain a mystery. We need these fossils, alongside their locality context, in order to learn as much as we can about our prehistoric planet. This is why, when visiting a national park with fossil resources, you’ll see signage and receive reminders about what to do when you find a fossil. Namely, you should photograph your fossil find, note its location (using GPS if possible, or capturing landmarks and features in your photos if not), and alert a park ranger right away. Picking up the fossil or disturbing it in any way would take away some or all of its locality context, which is one reason why it is prohibited. Following these guidelines can mean the difference between losing a fossil to time again or understanding our world just that little bit more—and the latter means the world to fossil-lovers everywhere. A special thanks to both the National Park Service Paleontology Program and the Paleontological Society, without whose collaboration and guidance through the Paleontology in the Parks Fellowship this project (and many other resources) would not exist.

Bibliography:

“How Fossils Form.” National Parks Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, 23 Oct. 2024, www.nps.gov/subjects/fossils/how-fossils-form.htm.

Sullivan, C.A. and Keenan, S.W., 2022, Experimental dissolution of fossil bone under varying pH conditions. PLOS ONE: v. 17, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0274084.

Unknown. “Brazil’s National Museum Hit by Huge Fire.” BBC News, BBC, 3 Sept. 2018, www.bbc.com/news/world-latin-america-45392668.

“Earl Douglass.” National Parks Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, 15 Feb. 2015, www.nps.gov/dino/learn/historyculture/douglass.htm.

Santucci, Vincent L. “The History of Paleontology in the National Park Service.” National Parks Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, 27 Jan. 2023, www.nps.gov/subjects/fossils/history-of-paleontology-in-the-national-park-service.htm.

Bibliography:

“How Fossils Form.” National Parks Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, 23 Oct. 2024, www.nps.gov/subjects/fossils/how-fossils-form.htm.

Sullivan, C.A. and Keenan, S.W., 2022, Experimental dissolution of fossil bone under varying pH conditions. PLOS ONE: v. 17, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0274084.

Unknown. “Brazil’s National Museum Hit by Huge Fire.” BBC News, BBC, 3 Sept. 2018, www.bbc.com/news/world-latin-america-45392668.

“Earl Douglass.” National Parks Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, 15 Feb. 2015, www.nps.gov/dino/learn/historyculture/douglass.htm.

Santucci, Vincent L. “The History of Paleontology in the National Park Service.” National Parks Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, 27 Jan. 2023, www.nps.gov/subjects/fossils/history-of-paleontology-in-the-national-park-service.htm.

Last updated: September 30, 2025