Last updated: March 13, 2024

Article

Locating Graves at Vicksburg National Cemetery

In August 2010, while preparing a grave site for a rare burial of a World War II veteran at the Vicksburg National Cemetery in the Vicksburg National Military Park in Vicksburg, Mississippi, cemetery workers were dismayed to find that the plot was already occupied by a casket. There was neither a headstone nor a record of interment in the space to suggest that the plot was occupied. Curious about the discovery, workers opened an adjacent plot, which was also believed to be empty. This, too, was occupied by an unmarked and unrecorded casket. The unmarked interments were located in newer sections of the cemetery that, according to records, were opened in the beginning of the 1940s. National Park Service (NPS) staff at Vicksburg promptly began efforts to identify the graves and determine if any more unmarked and unrecorded burials existed. NPS archeologists assisted park officials at Vicksburg National Cemetery to locate additional unmarked and unrecorded burials, and sift through decades of archives to identify the unknown, buried individuals.

National Cemeteries

In July of 1862, Congress passed legislation giving power to the president to purchase lands that would establish national cemeteries for soldiers that died in service of the United States. The first to be established was Arlington National Cemetery in Arlington, Virginia, in 1864. Today there are a total of 146 national cemeteries. Most are maintained by the Department of Veteran Affairs; two by the U.S. Army.

In 1933, at the onset of government reorganization, the NPS inherited 14 national cemeteries from the War Department, an earlier form of the current Department of Defense. Vicksburg National Cemetery is one of the 14 national cemeteries administered by the NPS. The earliest burials in NPS national cemeteries occur at Yorktown National Cemetery, within the Colonial National Historical Park in Virginia, which contains Revolutionary War burials. Additionally, the Chalmette National Cemetery, within the Jean Laffite National Historic Park and Preserve in Louisiana, has four burials from the War of 1812. The remaining 12 date to the Civil War and contain burials from fallen soldiers thereafter.

History of Vicksburg Cemetery

Vicksburg is the site of a key Civil War campaign that took place from early March to July 4, 1863, in which the Confederate Army commanded by General John C. Pemberton surrendered Vicksburg to General Ulysses S. Grant and provided the Union Army with vital access to the Mississippi River and Delta region. At the end of the Vicksburg siege, over 15,000 battle victims were scattered in burials hastily dug to prevent disease from spreading, with minimal resources and with few attempts to mark the deceased.

At the end of the Civil War, the United States government purchased 40 acres of land to serve as the final resting place for those who died during the battles in and around Vicksburg. One of the objectives was to identify and rebury soldiers to this tract of land.

By 1875, nearly all of the relocated Civil War deceased were transferred to the newly designated cemetery. Marble was used to distinguish the 16,588 graves, headstones to demarcate the identified individuals and blocks etched with a number for the unidentified burials. Over the next 50 years, the cemetery grew to accommodate more burials of Civil War, World War I, World War II, and Korean War veterans.

In 1961, Vicksburg Cemetery closed for future burials, with exceptions given to grave sites for veterans and widows who had reserved space. Today, the Vicksburg National Cemetery occupies 116 manicured acres high above the Mississippi River and includes more than 18,000 interments: 17,077 from the Civil War—of those, 12,909 are unknown soldiers. Records indicate that there are there are 61 outstanding reservations; although based on the date of reservation, some of those individuals are likely to have been buried elsewhere.

Identifying Unmarked Graves

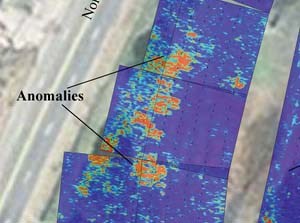

NPS staff at Vicksburg needed an effective, yet non-intrusive, means to identify additional, unmarked graves. They decided the best method was to use ground penetrating radar (GPR). GPR is a non-invasive surveying method used by archeologists and geophysicists to view subsurface inconsistencies. Similar to echolocation, in which a sound wave is bounced off objects to determine location, GPR emits electromagnetic waves into the ground and captures the reflected signal with an antenna connected to the machine. The results are viewed on a screen that displays the subsurface profile in two dimensional and three dimensional images. The natural electromagnetic properties of the soil rendered on the display appear in a uniform, undisturbed pattern. If any underground anomalies are present, such as a pipe or an animal burrow, they will reflect the electromagnetic waves differently than the adjacent soil and produce a noticeable pattern when displayed on the screen.

In order to obtain the best results, technicians drag the machine along transects in a gridded field. When looking for burials, it is important to consider the orientation of the signal that is emitted in relation to the orientation of the burial. Walking parallel to a grave will not display a reflected radar signal as well as walking perpendicular to a grave; therefore, a technician will cross over the same location to achieve the best image. Technicians then compile multiple data images from the results, and develop a layered image representing the subsurface contents at different depths.

GPR Investigations at Vicksburg

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers provided assistance in surveying possible unmarked gravesites. According to the final NPS reports (McNeil, 2011), surveyors detected a possibility of 62 unmarked graves within 1.7 acres of the cemetery’s land.

In January 2011, Superintendent Michael Madell requested assistance from the NPS Southeast Archeological Center to further investigate the anomalies using GPR. When they viewed their results, 27 more anomalies were located in this small amount of land. These results of the geophysical testing provided archeologists with high probability locations in which to begin subsurface excavation.

Excavations at Vicksburg

Using the GPR analysis as a guide, NPS archeologists conducted subsurface investigations to validate the results and determine the exact number of unmarked burials at the cemetery. In the spring of 2011, the archeologists began with systematic probing to test for obstructions in areas that showed anomalies in the subsurface profile images. Afterwards, archeologists used a backhoe to create shallow excavation trenches approximately 24.4 inches wide, averaging 11.8 inches deep, and between 6.5 feet and 88.5 feet long. The scraping technique provided archeologists with the ability to differentiate between false readings in the GPR results created by soil conditions, rocks, and other subsurface debris, and that of the actual grave shafts. Superintendent Madell stressed that the scraping was not deep enough to disturb any actual interments that might exist.

The shallow trenching proved to be the most effective method of subsurface anomaly identification. While sifting through the soil, a variety of glass, metal and ceramic fragments were uncovered. Their presence suggests an earlier structure may have existed at this location, and accounts for any skewed GPR results. Despite the disturbance displayed in the results, archeologists were able to determine that nine unmarked burials were in this area.

Backhoe scraping in another part of the cemetery revealed a mottled, highly rocky soil matrix, typically the result of backfill from construction projects. This explains the great amount of disturbance and false identifications in the GPR results. Archeologists were able to separate enough of the mottled fill and located one additional unmarked grave.

The combined GPR and subsurface testing approach was successful. After 83 trenches were partially excavated, a total of ten probable unmarked burials, in addition to the original two uncovered a year earlier that triggered the investigations, were located within approximately 273 feet of land. One last outstanding interment exists with only a small cement block and a partial number engraved in the block. This individual was included as the thirteenth unknown burial.

Identity of the Unknown

The location of 13 additional previously unknown graves was an unanticipated and exciting find. NPS staff attempted to identify the anonymous individuals who were buried. Due to the elapsed time, there was little hope of obtaining first-hand information about burials that are located in a tract of land acquired in the twentieth century, and potentially date to the 1940s.

NPS staff conducted a comprehensive review of archives and records in an attempt to identify the individuals who were buried in the unmarked graves. In addition, the NPS coordinated with outside agencies to examine records from local funeral homes, the Mississippi Department of Archives and History, the Department of Veterans Affairs, and National Archives facilities in both Washington, DC, and the Atlanta area, all without success.

“My staff and I searched all files and storage facilities located in the park without finding pertinent information,” Superintendent Madell said. “Regrettably, we must conclude that there are no records to indicate the names of the 13 souls who rest in these unmarked graves.”

Commemorating the Unidentified Veterans

The superintendent noted that the records search did result in the discovery of the names of approximately 130 spouses of veterans who had been properly recorded in files and buried next to their loved one, but whose names were never inscribed on the headstones. The NPS is working with the Department of Veterans Affairs to arrange for the names of those spouses to be added to the headstones. The Department of Veterans Affairs also will be providing a headstone inscribed with ‘Unknown’ for each of the 13 unmarked and unrecorded graves that were discovered.

“Though we are relieved to now know the results of our research,” said Superintendent Madell, “we also are very sad to learn that 13 individuals have had to rest in anonymity for several decades. These souls, be they veterans or spouses of veterans, deserve more respect and recognition. We apologize to them and to their families.”

Learn more about other projects related to finding graves in the National Cemetery:

Vicksburg National Cemetery Stabilization Project

References:

McNeil, Jessica. Archeological Investigations at Vicksburg. NPS Southeastern Archeological Center, Tallahassee, Florida. January 2011