Last updated: August 3, 2023

Article

Lincoln Boyhood National Memorial: Where Man and Memory Intersect (Teaching with Historic Places)

(Lincoln Boyhood National Memorial)

And sadden with the view;

And still, as memory crowds my brain,

There's pleasure in it too.1

Thus penned a thirty-five year-old Abraham Lincoln as he made a brief pilgrimage back to his boyhood home in 1844. Much had happened to him since his years growing up in Indiana. Now living in Illinois, Lincoln was a rising star in the state's Whig politics. He was on his way to fulfilling what he first wrote in 1832 that, “Every man is said to have his peculiar ambition. Whether it be true or not I can say for one that I have no other so great as that of being truly esteemed of my fellow men.”2 That journey began in the Hoosier State, and his roots can be found in Southern Indiana at Lincoln Boyhood National Memorial. Those seeking to uncover the real Abraham Lincoln will find here both the man and the myth.

In addition to preserving the site of the boyhood home of Abraham Lincoln where he lived for 14 years between the ages of 7-21, Lincoln Boyhood is significant because it represents that period within the history of the preservation movement when the creation of memorial edifices and landscapes was an important expression of the nation’s respect and reverence for Abraham Lincoln. The effort was spearheaded by the state of Indiana on behalf of all American citizens. Lincoln was, and is, a significant figure in our country’s history and this park preserves that most important formative period in his life.

2 "Communication to the People of Sangamo County," March 9, 1832, reprinted in Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, Vol. 1 (Rutgers University Press, 1990), 8.

About This Lesson

This lesson is based on the National Register of Historic Places registration file “Lincoln Boyhood National Memorial” and materials from the park. It was written by Mike Capps and was edited by Jim Percoco and the Teaching with Historic Places staff. This lesson is one in a series that brings the important stories of historic places into classrooms.

Where it fits into the curriculum

Topics: This lesson could be used in American history, social studies, and geography courses in units on the history of the presidency, mid-19th century party politics, or on Abraham Lincoln's life and presidency, or the formation of national identity. It could also be used in discussion on collective memory and interpretations of the past.

Time period: 1879-1962

Relevant United States History Standards for Grades 5-12

Lincoln Boyhood National Memorial: Where Man and Memory Intersect relates to the following National Standards for History:

Era 4: Expansion and Reform (1801-1861)

-

Standard 3B-The student understands how the debates over slavery influenced politics and sectionalism.

Era 5: Civil War and Reconstruction (1850-1877)

-

Standard 1A-The student understands how the North and South differed and how politics and ideologies led to the Civil War.

Curriculum Standards for Social Studies

(National Council for the Social Studies)

Lincoln Boyhood National Memorial: Where Man and Memory Intersect relates to the following Social Studies Standards:

Theme I: Culture

-

Standard C-The student explains and gives examples of how language, literature, the arts, architecture, other artifacts, traditions, beliefs, values, and behaviors contribute to the development and transmission of culture.

Theme II: Time, Continuity, and Change

-

Standard B-The student identifies and uses key concepts such as chronology, causality, change, conflict, and complexity to explain, analyze, and show connections among patterns of historical change and continuity.

-

Standard D-The student identifies and uses processes important to reconstructing and reinterpreting the past, such as using a variety of sources, providing, validating, and weighing evidence for claims, checking credibility of sources, and searching for causality.

Theme III: People, Places, and Environments

-

Standard A-The student elaborates mental maps of locales, regions, and the world that demonstrate understanding of relative location, direction, size, and shape.

-

Standard G-The student describes how people create places that reflect cultural values and ideals as they build neighborhoods, parks, shopping centers, and the like.

Theme IV: Individual Development & Identity

-

Standard A-The student relates personal changes to social, cultural, and historical contexts.

-

Standard B-The student describes personal connections to place—associated with community, nation, and world.

-

Standard C-The student describes the ways family, gender, ethnicity, nationality, and institutional affiliations contribute to personal identity.

-

Standard D-The student relates such factors as physical endowment and capabilities, learning, motivation, personality, perception, and behavior to individual development.

-

Standard E-The student identifies and describes ways regional, ethnic, and national cultures influence individuals’ daily lives.

-

Standard F-The student identifies and describes the influence of perception, attitudes, values, and beliefs on personal identity.

Theme V: Individuals, Groups, and Institutions

-

Standard E-The student identifies and describes examples of tensions between belief systems and government policies and laws.

Theme VI: Power, Authority, and Governance

-

Standard C-The student analyzes and explains ideas and governmental mechanisms to meet wants and needs of citizens, regulate territory, manage conflict, and establish order and security.

-

Standard D-The student describes the ways nations and organizations respond to forces of unity and diversity affecting order and security.

Theme X: Civic Ideals and Practices

Standard F-The student identifies and explains the roles of formal and informal political actors in influencing and shaping public policy and decision-making.

Objectives for students

1) To trace the evolution of Lincoln’s boyhood home from local efforts to maintain Nancy Hanks Lincoln’s grave to a national memorial to the Lincoln family;

2) To explain how Lincoln Boyhood National Memorial represents an important expression of the nation's respect and reverence for Abraham Lincoln;

3) To describe the creative process of building a memorial and to design a memorial;

4) To examine their own communities for memorials to commemorate individuals.

Materials for students

The materials listed below can either be used directly on the computer or can be printed out, photocopied, and distributed to students. The maps and images appear twice: in a low-resolution version with associated questions and alone in a larger, high-resolution version.

1) Two maps showing Indiana and the Lincoln Boyhood National Memorial Site;

2) Four readings about Lincoln as he is remembered, a history of the Nancy Hanks Lincoln's Memorial, how Lincoln is remembered both as man and as myth, and Indiana’s first national park;

3) Seven photographs of different aspects of Lincoln Boyhood National Memorial including the Nancy Hanks Lincoln gravesite and memorial panels.

Visiting the site

Lincoln Boyhood National Memorial, administered by the National Park Service, is open daily year round except January 1, Thanksgiving and Christmas. The park is located on Indiana Highway 162, 8 miles south of Interstate 64. Exit the Interstate at US 231 (exit 57) and travel south on U.S. 231 to the Gentryville/Santa Claus exit, then west on Indiana Highway 162, following the signs to “Lincoln Parks.” For more information, write to the Superintendent, Lincoln Boyhood National Memorial, 2916 E. South Street, P.O. Box 1816, Lincoln City, IN, 47552, call (812) 937-4541 or visit the park’s web site.

Getting Started

Inquiry Question

Setting the Stage

Abraham Lincoln was born on February 12, 1809 near Hodgenville, Kentucky to Thomas and Nancy Hanks Lincoln. The Lincoln family tree can be traced back to the Lincoln Family from Manchester, England who journeyed to the Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1636 as part of the great Puritan Migration (1620-1640). Subsequent family migration brought the family to New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and Virginia with Thomas finally establishing a homestead in Kentucky.

As a child and adolescent, Lincoln lived the life of a modest pioneer just west of the Appalachian Mountains. In an 1860 election pamphlet biography he said, “My life can best be summed up as the simple annals of the poor.”

Lincoln’s mother died when he was nine years old. His stepmother, Sarah Bush Lincoln, encouraged Lincoln to pursue his intellectual passions. This encouragement explains why American popular culture is filled with a young Lincoln reading at night by a hearth fire. Lincoln’s passion for knowledge led him to make a deliberate choice not to follow in his father’s footsteps, but to pursue a more intellectual career.

In 1830, Thomas moved the family to Illinois. From here Lincoln, now twenty-one, began his journey as a man and struck out on his own, moving to the town of New Salem, IL. It was in New Salem where Lincoln became interested in politics. He quickly rose in the Illinois Whig Party, a party dedicated to new ideas and promoting American economic growth. Throughout the 1850s, Lincoln continued to rise to national prominence. As a Whig and a supporter of free (wage) labor, Lincoln was vehemently opposed to slavery both on moral as well as economic grounds. Despite the success of his law practice, the repeal of the Missouri Compromise in 1854 drew him back into politics.

In 1860, Lincoln won the presidential election, leading seven southern slave holding states to secede by his inauguration in March 1861. For four years Lincoln worked hard to keep the Union together – his most important goal. In 1863, as a war measure, Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation ending slavery in those areas still in rebellion to the United States (four slave holding states Delaware, Maryland, Kentucky, and Missouri, the Border States remained in the Union). From 1863 to 1865, Lincoln managed to get Congress to support the 13th Amendment to the Constitution, which abolished slavery. By the time the war ended, slavery in the United States was dead and the Union was preserved.

Locating the Site

Map 1: Indiana and surrounding area, 1816.

(Lincoln Boyhood National Memorial)

The northern part of the state was unorganized at this time.

Questions for Map 1

1. What natural feature determined Indiana's southern boundary? What might have been some reasons frontier families settled near this feature?

2. Locate the Lincoln farm. How would you describe its location within the state of Indiana?

3. In what part of the state were most of the towns located at this time? Can you think of any reasons why that might have been?

Locating the Site

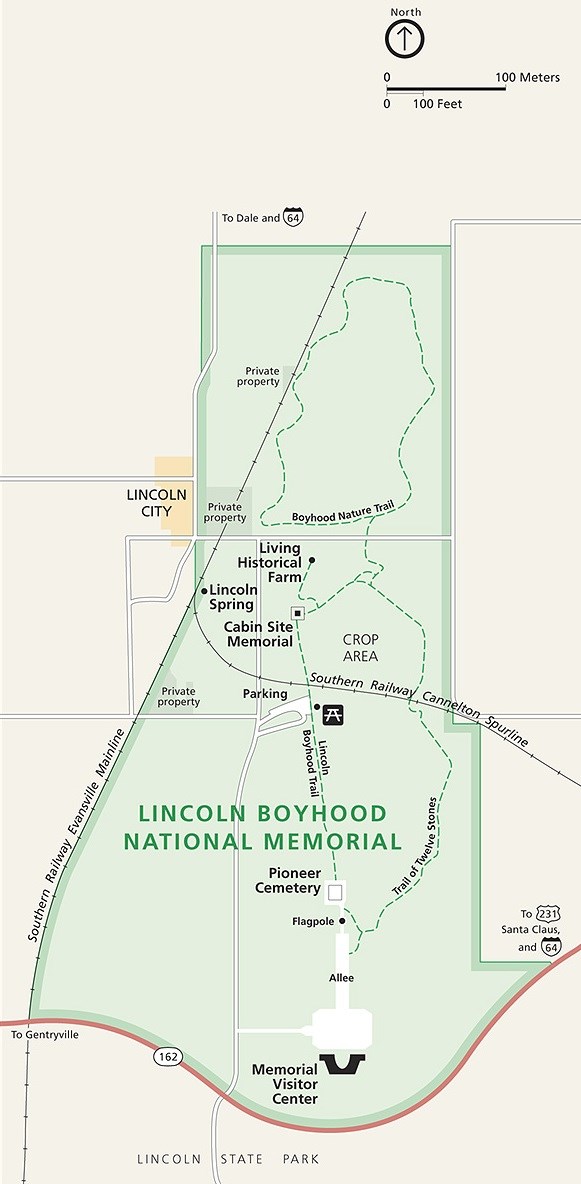

Map 2: Lincoln Boyhood National Memorial Site.

National Park Service map.

Questions for Map 2

1. Where is Nancy Hanks Lincoln’s gravesite? Where is the cabin site? Why do you think they are so far apart?

2. Where is the Living Historical Farm? What purpose do you think this serves at the memorial site?

Determining the Facts

Reading 1: Honoring Lincoln in Death

On April 14, 1865, President Lincoln became the last casualty of the Civil War. While attending a play at Ford’s Theater in Washington, DC, southern sympathizer John Wilkes Booth assassinated him. This tragedy took place on Good Friday. In Christian tradition, Jesus Christ died as a martyr on Good Friday. A martyr is someone who sacrifices himself or herself for other people. Some Americans after the Civil War saw Lincoln's death as a sacrifice for the nation and compared it to Christ's divine death.

Shortly after his death, Lincoln’s life became part of American legend. Some would say that process began with his two-week funeral ride. Millions of people flocked to see Lincoln one last time on his way from Washington, DC to Springfield, Illinois. Famous writers and ordinary citizens wrote poems in honor of the president. Artists took up their brushes to capture Lincoln drifting towards heaven in George Washington’s embrace. This type of image is referred to as, “Lincoln’s Apotheosis” – an elevation to divine status.

The following quotes from famous historical figures illustrate how revered Lincoln became after his assassination:

Henry Ward Beecher, Pastor, Brooklyn’s Plymouth Church – April 1865

“And now the martyr is moving in triumphal march, mightier than when alive. The nation rises up at every stage of his coming, Cities and states are his pallbearers, and the cannon beats the hours with solemn progression. Dead – dead – dead – he yet speaketh… Four years ago, O Illinois, we took from your midst an untried man…, we return him to you a might conqueror. Not thine anymore, but the Nation’s; not ours, but the world’s. Give him place, ye prairies.”1

George Bancroft, Historian, Funeral Oration in New York City’s Union Square – April 1865

“In sorrow by the bier we stand

Amid the awe that hushes all,

And speak the anguish of a land

That shook with horror at thy fall.”2

Poet Henry Howard Brownwell, Abraham Lincoln, War Lyrics and Other Poems (1866), Washington, DC – May 1863

“Close round him, hearts of pride!

Press near him, side by side, –

Our Father is not alone!

For the Holy Right he died,

And Christ, the Crucified

Waits to welcome his own.”3

Sculptors designed statues to honor Lincoln’s memory within a few years of his death. The themes ranged from Lincoln as the Great Emancipator, to the boy Lincoln, to the respected statesman, and Commander-in-Chief. More than 225 statues honor Lincoln. This is more than any other figure in American history. People can find the story of Lincoln, the man and the myth, all around them.

Questions for Reading 1

1. On what day did President Lincoln die? How did this influence how the country remembered him?

2. In what ways are all of these reflections about the life of Abraham Lincoln similar? How would you describe these reflections? Do you see a pattern in what parts of the country these writings come from? Why does geography make a difference?

3. What does “Lincoln’s Apotheosis” refer to? What other famous historical figure is part of this image? Why do you think he is there? What are the various portrayals of Lincoln? Who else has received as many memorials (including statues) as Lincoln?

4. Can you think of any other public figures in the 19th and 20th centuries who have been memorialized because they were killed for their beliefs? How has society remembered those people? Are certain people remembered more than others? Why might that be?

Reading 1 was adapted from Merrill D. Peterson's, Lincoln in American Memory (New York: Oxford University Press, 1994).

1 Merrill D. Peterson, Lincoln in American Memory (New York: Oxford University Press, 1994), 18.

2 Ibid.

3 Ibid, 23.

Determining the Fact

Reading 2: Honoring Nancy Hanks Lincoln

Visiting the graves of famous people is a common practice. For many, these are personal pilgrimages. Abraham Lincoln once wrote, "All I am and hope to be I owe to my mother." From the limited accounts we have of Nancy Hanks Lincoln, she was a kind and loving mother to Abraham and his sister, Sarah. Lincoln's mother died on October 5, 1818, he was only nine years old. Nancy was a victim of milk sickness. This was a condition passed on to humans through cows that ingested white snakeroot. Lincoln and his father, Thomas, built Nancy's coffin out of a tree they cut down. She was laid to rest in what came to be known as the Little Pigeon community. After his first wife's death, Thomas Lincoln sought a new bride who could take care of his children. He married Sarah Bush Johnston in 1819. After the Lincolns moved to Illinois in 1830, Thomas's property was broken up through various sales. Over time, new residents ignored Nancy Hanks Lincoln's gravesite. It would not be until 1865 that the spotlight would shine again on her resting place.

The first public mention of Nancy Hanks Lincoln's grave was in 1868. Civil War veteran William Q. Corbin visited Lincoln's home site and was shocked at the neglected state of Nancy's grave. He wrote a poem that appeared in the Rockport Journal in November of 1868. Corbin's poem inspired Gentryville residents meet to discuss what to do. Nothing happened immediately, but interest in marking the grave continued. Finally, in 1874, a Rockport businessman placed a two-foot tall marker, inscribed with Nancy Hanks Lincoln's name, on the site.

Unfortunately, the site continued to suffer from neglect and theft of the markers. The 1874 marker was gone by 1879. It was replaced that same year. Area residents contributed to building an iron fence around the grave to protect it. Care for the grave fell to whoever took on the task. To address this problem Indiana Governor James E. Mount called for a meeting of several state patriotic organizations on June 30, 1897. The outcome was the creation of the Nancy Hanks Lincoln Memorial Association. This group had two purposes: to raise money for the maintenance of the gravesite and to promote an Indiana memorial to the Lincolns.

Over the next decade, the Nancy Hanks Lincoln Memorial Association raised funds to improve the site. Robert Todd Lincoln and others made donations to the site. Their funds helped to purchase the 16 acres surrounding Nancy's gravesite. In 1902, J.S. Culver carved a monument to place in front of Nancy's grave marker. Culver owned a stone company that had worked on Lincoln's tomb in Springfield, Illinois. The stone he placed at Nancy's grave came from his monument to Lincoln in Springfield. A graveside dedication took place on October 1, 1902.

By 1906, the gravesite was in bad shape once again. The governor of Indiana and the Nancy Hanks Lincoln Memorial Association met to address the problem. The meeting led to the creation of a state commission in 1907. One of the first issues addressed was protecting the site. The legislature gave $5,000 for the construction of an ornamental fence around the 16-acre park.

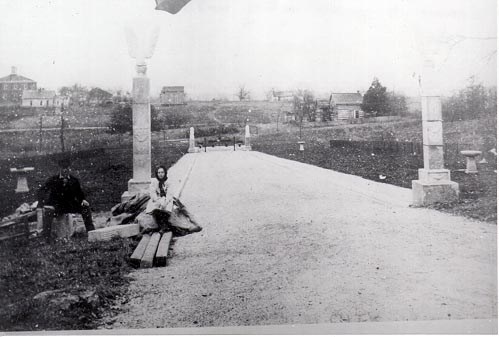

In 1909, the Indiana State Board of Commissions made improvements to Nancy Lincoln's gravesite. They cleared the park of dead trees, built an ornamental iron fence around the 16 acre park (including an entrance gate), and a paved road from the highway to the gravesite of Lincoln's mother. The highway entrance featured life-size lions. Closer to the gravesite, south of the lions, eagles perched on columns. Large stone urns sat along the roadway to the cemetery.

In December 1916, Indiana celebrated 100 years as a state. To celebrate, Indiana identified important sites in its history. In 1917, the state selected what is believed to have been Thomas Lincoln's cabin site. This selection created great interest in the historic Lincoln property. Nancy Hanks Lincoln's grave was an important part of the cabin site's significance. Seen as part of the "cult of motherhood," people believed Nancy played an important role in Abraham's life. The "cult of motherhood" placed great importance on a mother's influence in her children's lives. This view of motherhood came from the Victorian Era (named for England's Queen Victoria who reigned from 1837-1901). Lincoln's oft-quoted statement about his "angel mother" did much to support the idea of the "cult of motherhood."

In the 1920s, various newspapers expressed unhappiness that Indiana did not have a proper state memorial to Abraham Lincoln. In 1925, the state assembly created the Lincoln Memorial Commission. This commission had authority to purchase land and build structures as needed. Its goal was "to prepare and execute plans for erecting a suitable memorial to the memory of Abraham Lincoln at or near his residence in the state." The Department of Conservation took over care of Nancy's gravesite the same year.

Questions for Reading 2

1. At least how many attempts were made to mark the gravesite of Nancy Hanks Lincoln before the marker that is currently there was put into place? When was the current marker erected?

2. Did any members of the Lincoln family contribute to the maintenance of Nancy’s gravesite? Who else was involved? What kinds of things did they do?

3. What is the “cult of motherhood”? How did this influence the efforts to memorialize Nancy Hanks Lincoln’s grave? Do you think it makes sense to honor Nancy Hanks Lincoln in this way? Explain.

4. When was it decided that a memorial would be built? Who was in charge? What do you think a “suitable” memorial requires?

Reading 2 was adapted from The Lincoln Notebook, prepared by the staff of Lincoln Boyhood National Memorial.

Determining the Facts

Reading 3: Honoring Abraham Lincoln: The Man and the Myth

Designers had to keep several factors in mind when they began to plan the memorial. One of those factors was the high esteem people had of Lincoln. By the beginning of the 20th century, his image as a hero was established. He was the Preserver of the Union, the Great Emancipator, the author of the Gettysburg Address, the Martyred President. All things associated with his life took on great significance. Anything attached to Lincoln was a possible memorial. Lincoln often referred to his Indiana home site as the “very spot where grew the bread that formed my bones.” Adding great importance to this site was Nancy Hanks Lincoln’s grave. Lincoln spoke very highly of his “angel mother” therefore preserving her gravesite properly was a priority. It was a guiding source in the development of the memorial site.

First Phase of Lincoln Boyhood National Memorial

The first order of business in building a memorial was to clean up Nancy Hanks Lincoln’s gravesite. Colonel Richard Lieber, the director of the Department of Conservation, and the Indiana Lincoln Union (ILU) beautified the site (cleaned up branches, made the land look nice). The ILU was a group of private citizens. Their goal was to, “propose that the people of the state, in mighty unison, rear a national shrine which…will express both our deathless devotion as well as our indefinite gratitude to the soul of the great departed and his Mother.”

Once Nancy Hanks Lincoln’s gravesite was cleaned up, Colonel Lieber and the ILU hired landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr. to prepare a design for Abe Lincoln’s memorial. Like his famous father, Olmsted had experience working on a number of city park systems. He visited the site in March 1927 to get some ideas. In May, he returned to present his design to the board. Recognizing that Indiana was an important part of forming who Lincoln became, Olmsted believed that the memorial should reflect the importance of the site. As a first step, he set guidelines for simplifying the area surrounding the grave and the cabin site. He called these areas “the Sanctuary.” He declared that it “should be freed of every petty, distracting, alien, self-asserting object.” The goal was to make “it easy and natural for…people...to be stimulated to their own inspiring thoughts and emotions about Lincoln.”

To help commemorate Lincoln’s experience in Indiana, designers created a cabin site memorial. Instead of building a replica of Lincoln’s cabin, the state hired architect Thomas Hibben, a native of Indiana, to design a suitable monument to mark the site. Hibben planned a bronze casting in the shape of the historic cabin sill (a shelf or slab of stone, wood, or metal at the foot of a window or doorway) and hearth (the floor of a fireplace). The sill and hearth would be surrounded by a stone wall. The area was to be formally landscaped.

While the cabin site memorial was being constructed, J.I. Holcomb, president of the Indiana Lincoln Union suggested another major design feature. Holcomb wanted to install a series of twelve stones, gathered from places associated with Lincoln, as miniature shrines along a wooded trail to interpret Lincoln’s life. A promotional piece described the trail by stating, “Each shrine will be especially landscaped to emphasize its historical significance.” Although the Trail of Twelve Stones was not part of the original plan, it provided a physical and figurative link between the cabin and gravesite. The connection of Lincoln’s childhood home to his mother’s grave with an allée (a walkway through a park or landscape), created a sort of pilgrimage for visitors. As they walk through the site, they learn about and reflect upon the different stages of Lincoln’s life. The trail also represented the sad story of Lincoln’s childhood: the passage from innocence into maturity upon the death of his mother and his eventual sacrifice for the nation.

In 1934, a Civilian Conservation Corps crew (a federal program during the Great Depression, also called the CCC) located and excavated the historic hearthstones. The CCC constructed a stone wall and landscaped the grounds. The bronze casting was finally placed on the site in July of 1935. This casting completed the first phase of the memorial’s development.

Second Phase of Lincoln Boyhood National Memorial

The second phase of the memorial was to construct a memorial building. This building sits to the south of the gravesite and cabin. Its placement allows the gravesite and cabin site to be the focus for visitors. From the memorial building, visitors are lead towards Nancy's grave and then on to the cabin site.

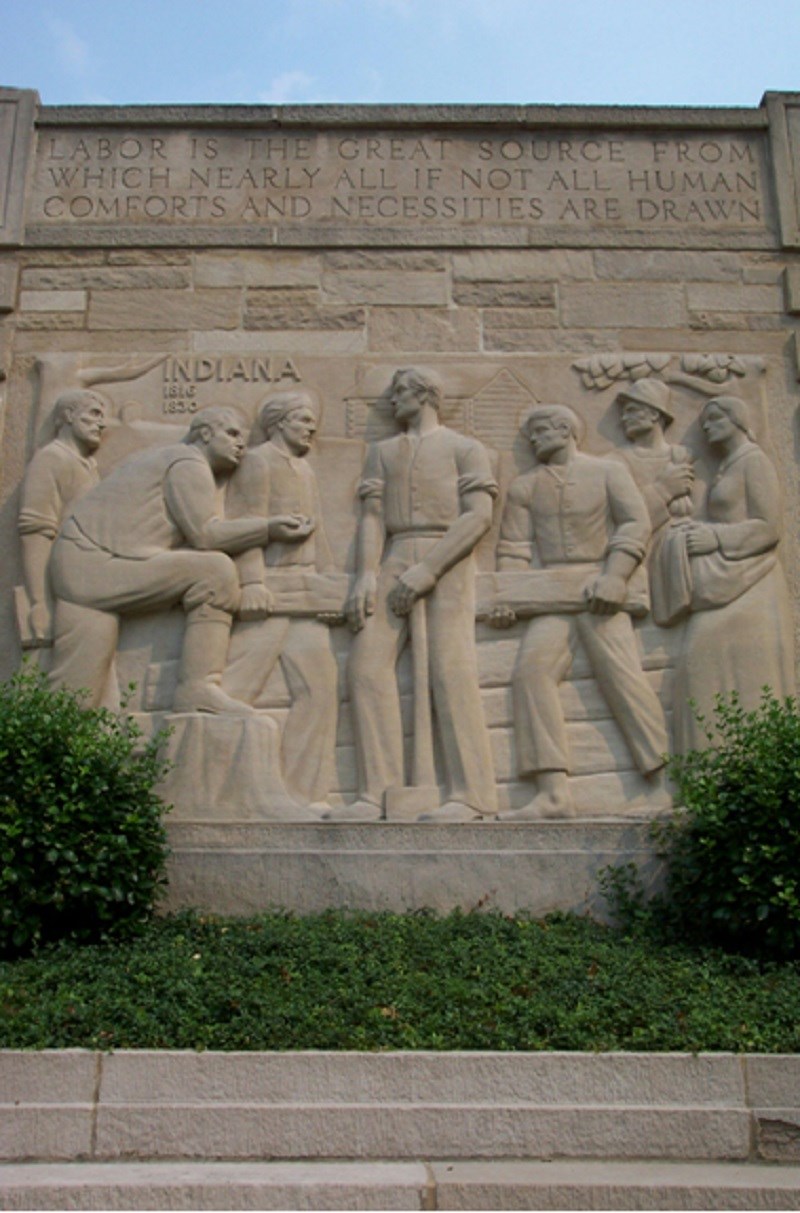

For the design of the building, Lieber looked to the National Park Service for inspiration. Lieber chose Richard E. Bishop to design the memorial building. Bishop designed a structure with two square buildings joined by a semicircular cloister (a covered walkway). One building was for Nancy and the other was for Abraham. Memorial planners liked Bishop's plan and he was hired to draw up more. In his design for the cloister, Bishop included five sculptured panels separated by four large openings. Each panel represented Lincoln's life in Kentucky, Indiana, Illinois, and Washington, DC. The fifth panel represented the deceased president's significance to all Americans. Above the doorways, passages from Lincoln's speeches would be carved in stone.

An important part of Bishop's design was the materials used. Bishop wanted materials from 19th century Indiana to be used for the building as much as possible. The ILU gave out the money to begin construction in late 1940. Hand-cut limestone came from Bloomington, Indiana. The Department of Conservation provided native timber and finished lumber. The cherry table, chairs, benches, and pews were custom made.

Work on the sculptured panels began in 1941. The ILU hired Elmer H. Daniels as the sculptor. Daniels set up a studio in nearby Jasper in September of that year. He began preparing pencil sketches followed by 16 x 27-inch clay models.When an oversight committee approved of these, Daniels prepared half-scale clay models of each panel. Those clay models became plaster casts. Five limestone panels weighing 10 tons and measuring 8 feet tall by 13 ½ feet wide were cut. By the spring of 1942, stone carvers hired by the Department of Conservation had completed the panels and in 1944 the building was finished and opened up to the public. A caretaker lived on the property to maintain the site.

Questions for Reading 3

1. Who was the first landscape architect assigned to design the memorial site? What type of environment did he want to create?

2. What is the Trail of Twelve Stones? What does it represent at this site?

3. What are the three units of the memorial building? How many panels are there and what do they represent? Why do you think it was important to use building materials from the state of Indiana?

4. What are some the names Lincoln is remembered by? How does this affect sites that are associated with him? What do you think of the process of remembering a person through a place? Do you think that is a good model?

Reading 3 was adapted from The Lincoln Notebook, prepared by the staff of Lincoln Boyhood National Memorial.

Determining the Facts

Reading 4: Lincoln Boyhood National Memorial Becomes Indiana's First National Park

In the late 1950s, Indiana moved to make the Nancy Hanks Lincoln Memorial Park a national park. On February 19, 1962, President John F. Kennedy signed legislation to make the memorial park a national park. With this new designation, the National Park Service took ownership of the site. Nancy Hanks Lincoln Memorial Park became Lincoln Boyhood National Memorial, Indiana's first authorized unit of the National Park Service.

When the National Park Service took over, they had several goals to improve the site. The first goal was to move the direction of Highway 162. The highway was supposed to run in front of the memorial building. The Park Service had it redirected to pass to the south of the memorial building. Another goal was to build a visitor center. This space would provide site visitors information, orientations, and basic service facilities. Finally, the Park Service wanted a building for a lobby, an exhibit room, and a 100-seat auditorium.

Ultimately, the National Park Service decided to work with the existing design of the site. They focused on improving the available buildings. One of the first projects was to enclose the cloister between the Nancy Hanks Lincoln Hall and the Abraham Lincoln Hall. Building a museum and auditorium came next. Native St. Meinrad sandstone and cherry paneling were used to build these additions. The new visitor center was officially dedicated on August 21, 1966.

When it came to telling Lincoln's story at the site, the Park Service did not have any of the original buildings. The solution was to build the Lincoln Living Historical Farm in 1968. Instead of reconstructing the Lincoln farm, the Park Service recreated a farm from the 1820s. The site did not have enough information about the Lincoln farm to recreate it. Building a farm from the same time period would help visitors understand what life was like for the Lincolns and other Indiana pioneers. An archaeological dig was done to look for the historic farm but nothing was found. Ground clearing began in February 1968. By April, the buildings and fences were standing.

All of the logs for the buildings came from old structures found in Spencer, Indiana and surrounding counties. It generally took one day to knock down the old building, another day to move it, and approximately two weeks to rebuild it on site. When construction of the farm was finished, it included a log cabin, log barn with shed, a smokehouse, a corncrib (a building used to dry and store corn), a chicken house, and a workshop. Split rail fences enclosed the farm. Using research about 19th century farm life, park staff was able to provide a living history interpretation of the site.

The completion of the living historical farm was the final piece of the Lincoln Boyhood National Memorial. Visitors to the park today have a number of options to learn about Lincoln. They can tour the museum and memorial halls, watch the movie in the park auditorium, observe pioneer skills demonstrations at the farm, walk the trail to the gravesite and the historic Trail of Twelve Stones, and participate in a variety of ranger-led interpretive programs. Lincoln Boyhood National Memorial is the premier Lincoln site in Indiana and one of the most significant in the country.

Questions for Reading 4

1. When did the site become a part of the national park system? Who made it a national park? How long after the Civil War was the site made a national park? Why do you think that might have been?

2. What kinds of changes did the National Park Service make to the site? Were the earlier features of the site retained or replaced? Why is this important?

3. Is the present day farm original? Is it located on the original site? What is the purpose of the farm? Do you think it fits with the earlier developments?

4. Do you agree with the interpretation and presentation of this important site? What things would you change if you could to make the portrayal of Lincoln’s life there better?

Reading 4 was adapted from The Lincoln Notebook, prepared by the staff of Lincoln Boyhood National Memorial.

Visual Evidence

Photo 1: Nancy Hanks Lincoln Gravesite (c. 1880s).

(Lincoln Boyhood National Memorial)

(Lincoln Boyhood National Memorial)

(Lincoln Boyhood National Memorial)

Questions for Photos 1-3

1. Compare the three photographs. What is the same and what has changed?

2. Other people were buried in the area where Nancy Hanks Lincoln is buried. Do you see any other markers in Photo 1? Based on what you have read, why do you think that might be? Do you think the family had a marker like this on her grave during the time they were living in Indiana? Why or why not?

3. Why do you think a fence was put up around the gravesite? (Refer to Reading 2, if necessary)

4.Where did the larger stone in Photo 2 come from? (Refer to Reading 2, if necessary) Do you think it is an important improvement to the memorial site or not? Explain your answer.

Visual Evidence

Photo 4: View north from the gravesite, circa 1910s.

(Lincoln Boyhood National Memorial)

(Lincoln Boyhood National Memorial)

Questions for Photos 4-5

1. Who owned the site when these photos were taken? What was the state’s involvement? (Refer to Reading 2, if necessary)

2. Compare the two photographs. What feature can you see in both photographs? How has the feature changed from photo 4 to photo 5? What else has changed? How much work has been done in the time between the two photographs?

3. How does the area inside the park differ from the area outside the park? What might account for that?

Visual Evidence

Photo 6: Indiana Memorial Panel as it looks today.

(Lincoln Boyhood National Memorial)

This panel of Lincoln’s life in Indiana is one of five panels on the memorial building at the Lincoln Boyhood National Memorial that represents the different phases of Lincoln’s life.

Questions for Photo 6

1. Which one of the figures do you think is Lincoln? Why? What years of his life does this panel represent? In what ways does the panel reflect what you learned in the readings?

2. The inscription is a quote from Lincoln. What is the relationship between the text and the carved figures? What is Lincoln holding? Can you think of one of Lincoln’s nicknames that this represents (if not, do an internet search of “Lincoln” and the name of the tool he is holding)?

3. What other symbols related to Abraham Lincoln’s youth can you find in this picture? What Lincoln “themes” do they represent? Do you think this panel reflects a national veneration of Lincoln? Why or why not?

Visual Evidence

Photo 7: Lincoln Memorial Hall.

(Lincoln Boyhood National Memorial)

Questions for Photo 7

1. Based on what you have learned in this lesson, how does this space reflect a reverent attitude towards Abraham Lincoln?

2. Do you think this is a good way to get people to think about Lincoln and his ideas? Why or why not? What would you do differently to promote reflection on Lincoln’s life?

Putting It All Together

The following activities help students put their knowledge of the Lincoln Boyhood National Memorial into a broader perspective.

Activity 1: Designing a Memorial

Have students divide into groups, then ask each group to decide on an American-male or female, historic or contemporary-whom they believe should be honored with a memorial. Next, have them list the characteristics that should be represented for that person. Students will then develop two or three ideas about how their idea could be executed in a purely symbolic design. Remind the students that a symbol is something that stands for or suggests something else by reason of relationship, association, or convention. Have students decide on symbols they will use in their monument in place of a portrait or likeness of the person they are memorializing.

Working together with whatever supplies you and the groups can muster, have the students create a model of their memorial. The model can be simple (made of crayon-decorated paper for example) or complex (such as being modeled of clay and stucco or wooden building supplies). Each group should include a written description of the ideas behind the structure with its final project. Have students present their memorials to the class and explain why they chose the person and symbols that they did. Have students note if there any common themes in the type of people chosen or the character traits represented. Are they political figures? Sports figures? Actors? Musicians? Humanitarians? Etc.

Activity 2: The Lincoln Portrait

Play Aaron Copland’s “Lincoln Portrait” for students. This was a musical and narrative composition written by the great American composer Aaron Copland in 1942. His goal was to inspire the nation to victory during World War II, using Lincoln’s life as a means to rally Americans to patriotism. Have students listen to the recording and compare and contrast it with parts of the Lincoln Boyhood Memorial. What connections can they make? How so? Do the students think that music can be equally powerful to inspire people compared to a physical memorial? Hold a class discussion about how art inspires us.

Activity 3: Local Memorial Study

Most communities memorialize their local heroes. Many memorials stand in front of, or inside of, public buildings such as town halls, courthouses, or school buildings; often those buildings themselves are named after someone in order to commemorate that person. Not all memorials enjoy such prominence however, they may be small or stand in out-of-the-way places. Some memorials consist of a building, road, bridge, school park, or school named for a person. Have the students think of all the ways that their community or region has memorialized people. You may want to have them ask their parents, neighbors, or other adults for ideas. Then have the students, individually or in groups, select a local memorial to research. Ask them to select one that was specifically designed to be a memorial. They should identify the person being memorialized, investigate the memorial, and report back to the class. Their report should try to answer the following questions: What did the person do to be considered worthy of a memorial? How long after a person’s death was the memorial conceived? What individuals or groups remained most active in advocating the memorial? Did they encounter any opponents? What design criteria existed, if any? How did the location of the memorial become selected? Was it a prominent one? If so, is it still prominent? Is the person memorialized still well known and still considered a hero? Why or why not?

Resources for students may include local or national histories and biographies, newspaper clippings, interviews (oral history), photographs, or other resources. The student or the groups should visit the site of the memorial and either take a photograph or make a drawing to share with the class. Have each student or group report their findings to, and share pictures with, the class. Post the pictures on bulletin boards and hold a class discussion to compare the design of memorials from different eras. Offer to exhibit the pictures with brief interpretive paragraphs written by the students in the school library for the whole school to view. You might even consider offering them for display at a local library or historical society.

Lincoln Boyhood National Memorial: Where Man and Memory Intersect --

Supplementary Resources

By studying Lincoln Boyhood National Memorial: Where Man and Memory Intersect students learn how the nation has honored Abraham Lincoln, the man and the myth. Those interested in learning more will find that the Internet offers a variety of interesting materials.

National Park Service, Lincoln Home National Historic Site

Lincoln Home National Historic Site is a unit of the National Park Service. The Lincoln home, the centerpiece of the Lincoln Home National Historic Site, has been restored to its 1860s appearance, revealing Lincoln as husband, father, politician, and President-elect. It stands in the midst of a four block historic neighborhood in Illinois that the National Park Service is restoring so that the neighborhood, like the house, will appear much as Lincoln would have remembered it. The Lincoln Home National Historic Site web page contains information on visiting the historic site, information on the Lincoln family, information on the issues of freedom and democracy that Lincoln and his contemporaries were facing, virtual tours of the Lincoln Home and neighborhood, and much more.

National Park Service, Abraham Lincoln Birthplace National Historic Site

Lincoln's Birthplace in Hodgenville, Kentucky is a unit of the National Park Service. The Abraham Lincoln Birthplace National Historic Site contains information on visiting the historic site, the Lincoln family's migration in America and life on the frontier.

Library of Congress: Historic American Buildings Survey (HABS)/ Historic American Engineering Record (HAER) Collection

Search the HABS/HAER collection for detailed drawings, pictures, and documentation from their survey of the Lincoln Home Site in Springfield, Illinois. HABS/HAER is a division of the National Park Service.

Library of Congress--American Memory Collection

The complete Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress consists of approximately 20,000 documents. The collection is organized into three "General Correspondence" series which include incoming and outgoing correspondence and enclosures, drafts of speeches, and notes and printed material. Most of the items are from the 1850s through Lincoln's presidential years, 1860-65. Treasures include Lincoln's draft of the Emancipation Proclamation, his March 4, 1865, draft of his second Inaugural Address, and his August 23, 1864, memorandum expressing his expectation of being defeated for re-election in the upcoming presidential contest.

National Archives--The Emancipation Proclamation

President Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863, as the nation approached its third year of bloody civil war. The proclamation declared "that all persons held as slaves" within the rebellious states "are, and henceforward shall be free."

Illinois Historic Preservation Agency

The Papers of Abraham Lincoln is a long-term project dedicated to identifying, photographing, and publishing, both comprehensively in electronic form and selectively in printed volumes, all documents written by or to Abraham Lincoln during his entire lifetime (1809-1865).

Abraham Lincoln Historical Digitization Project

Lincoln/Net, supported by Northern Illinois University and the Illinois State Library, presents historical materials from Abraham Lincoln's Illinois years (1830-1861), including Lincoln's writings and speeches, as well as other materials illuminating antebellum Illinois.

Indiana Historical Society

IHS acquired three nationally significant Lincoln collections, the Jack Smith Lincoln Graphics Collection, the Daniel R. Weinberg Lincoln Conspirators Collection, and the Alexander Gardner Lincoln Glass Plate Negative. The Smith collection consists of over 700 original photographs, lithographs, engravings, and busts of Lincoln. The Weinberg collection consists of photographs, manuscripts, books, pamphlets, and newspapers relating to the trial and execution or imprisonment of the Lincoln assassination conspirators. The centerpiece of this collection is the original collodion wet-plate negative of the portrait of Abraham Lincoln made by Alexander Gardner. Lincoln sat for this photograph on 8 November 1863, just 11 days before delivering the Gettysburg Address.

Abraham Lincoln Bicentennial 2009

The Abraham Lincoln Bicentennial Commission was created by Congress to inform the public about the impact Abraham Lincoln had on the development of our nation, and to find the best possible ways to honor his accomplishments. The President, the Senate and the House of Representatives appointed a 15-member commission to commemorate the 200th birthday of Abraham Lincoln and emphasize the contribution of his thoughts and ideals to America and the world. A timeline, speeches, online resources, and a photo gallery are available via this website.