Last updated: June 26, 2023

Article

Lincoln Boyhood National Memorial: Forging Greatness during Lincoln's Youth (Teaching with Historic Places)

National Park Service

In the newly formed state of Indiana on the western frontier, Abraham Lincoln spent 14 of the most formative years of his life growing from youth into manhood (1816-1830). Many of the character traits and moral values that made Abraham one of the world's most respected leaders were formed and nurtured here. It was here on a rural farm that he learned to laugh with his father, cried over the death of his mother, read the books that opened his mind, and triumphed over the adversities of life on the frontier.

Lincoln Boyhood National Memorial, a unit of the National Park Service, preserves the site of the farm where Abraham Lincoln spent his life from the ages of 7 to 21. The park includes a memorial visitor center built by the state of Indiana in the 1940s; a cabin site memorial; the cemetery where his mother, Nancy Hanks Lincoln, is buried; and a recreated living history farm where visitors can experience frontier life.

About This Lesson

This lesson about Abraham Lincoln in Indiana is based on the National Register of Historic Places registration file, "Lincoln Boyhood National Memorial" (with photographs) and materials from Lincoln Boyhood National Memorial. It was written by Mike Capps, Chief of Interpretation and Resource Management at Lincoln Boyhood National Memorial. The lesson plan was edited by the Teaching with Historic Places staff. This lesson is one in a series that brings the important stories of historic places into classrooms across the country.

Where it fits into the curriculum

Topics: This lesson could be used in American history, social studies, and geography courses in units on early 19th century frontier life, history of the presidency, or an introduction to Abraham Lincoln's life and presidency.

Time period: 1816-1830

United States History Standards for Grades 5-12

Lincoln Boyhood National Memorial: Forging Greatness during Lincoln's Youth

relates to the following National Standards for History:

Era 4: Expansion and Reform (1801-1861)

-

Standard 2E- The student understands the settlement of the West.

-

Standard 3B- The student understands how the debates over slavery influenced politics and sectionalism.

Curriculum Standards for Social Studies

(National Council for the Social Studies)

Lincoln Boyhood National Memorial: Forging Greatness during Lincoln's Youth

relates to the following Social Studies Standards:

Theme II: Time, Continuity and Change

-

Standard D - The student identifies and uses processes important to reconstructing and reinterpreting the past, such as using a variety of sources, providing, validating, and weighing evidence for claims, checking credibility of sources, and searching for causality.

Theme III: People, Places and Environments

-

Standard D - The student estimates distance, calculates scale, and distinguishes other geographic relationships such as population density and spacial distribution patterns.

Theme IV: Individual Development & Identity

-

Standard C - The student describes the ways family, gender, ethnicity, nationality, and institutional affiliations contribute to personal identity.

-

Standard D - The student relates such factors as physical endowment and capabilities, learning, motivation, personality, perception, and behavior to individual development.

-

Standard F - The student identifies and describes the influence of perception, attitudes, values, and beliefs on personal identity.

Objectives for students

1) To identify several events and people from Abraham Lincoln's youth that influenced the development of his character and personality.

2) To understand the daily life of a pioneer in the 1820s and identify specific skills that the Lincoln family needed to survive on the frontier.

3) To determine how Lincoln's youthful frontier experience influenced his beliefs, actions, and attitudes as President of the United States.

4) To research a historic site in their community associated with an important historical figure.

Materials for students

The materials listed below either can be used directly on the computer or can be printed out, photocopied, and distributed to students. The maps and images appear twice: in a smaller, low-resolution version with associated questions and alone in a larger version.

1) three maps of the Lincoln family migration route, Indiana, and the Little Pigeon Creek Community;

2) four readings about Lincoln's boyhood, life on the frontier, and his character as president;

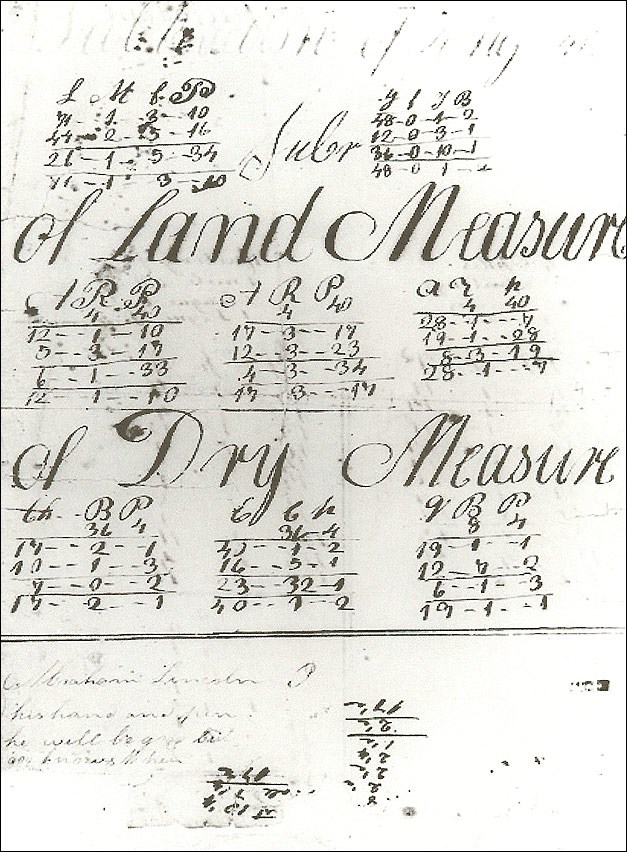

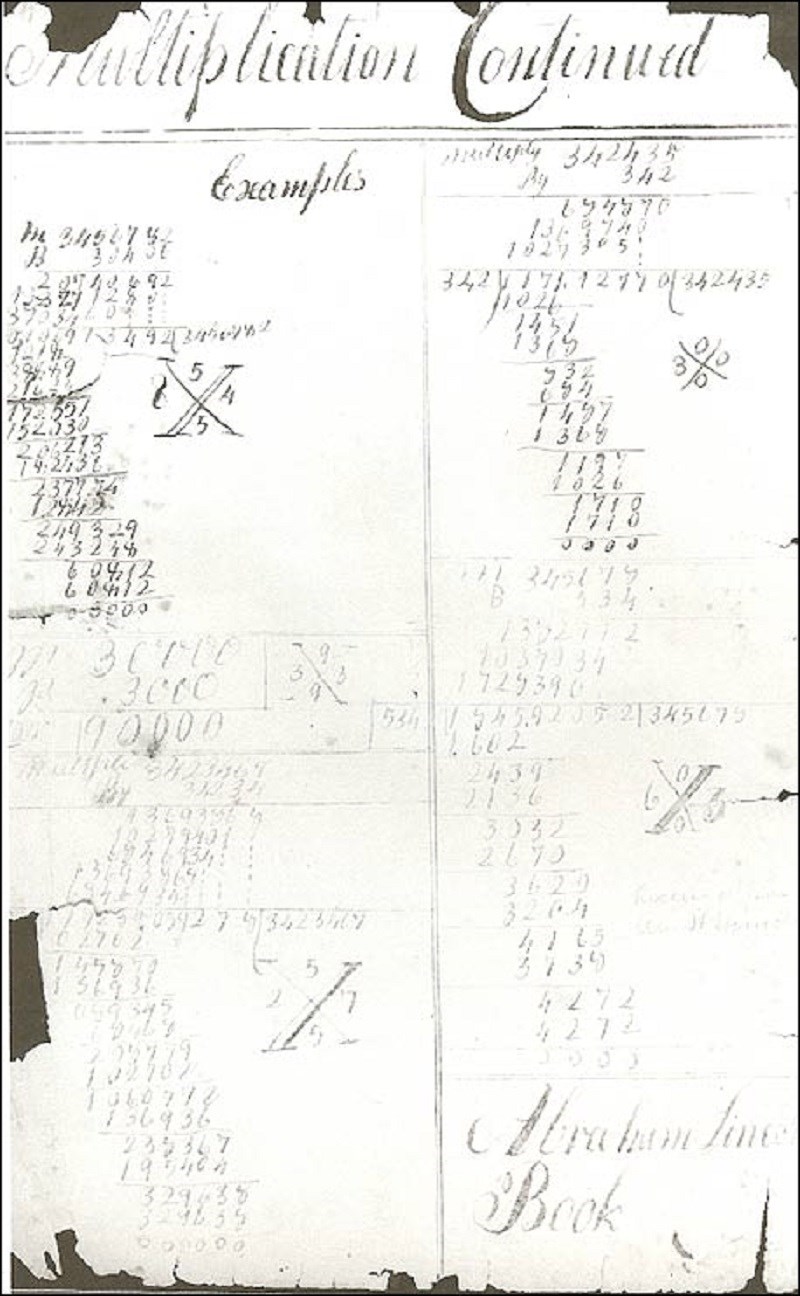

3) two illistrations of Lincoln's sum book pages;

4) five images of the Nancy Hanks Lincoln's gravesite and Lincoln cabin memorial, a reconstructed cabin, and living history at the farm;

Visiting the site

Lincoln Boyhood National Memorial, administered by the National Park Service, is open daily year round except New Year's Day, Thanksgiving, and Christmas. The park is located on Indiana Highway 162, 8 miles south of Interstate 64. Exit the Interstate at US 231 (exit 57) and travel south on U.S. 231 to Gentryville, then east on Indiana Highway 162, following the signs to "Lincoln Parks." For more information, write to the Superintendent, Lincoln Boyhood National Memorial, P.O. Box 1816, Lincoln City, IN 47552, or visit the park's website.

Getting Started

Inquiry Question

National Park Service photo.

What do you think the original structure might have been?

Setting the Stage

In the years following the War of 1812, emigration to the Old Northwest--an area that would eventually become the states of Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Michigan, and Wisconsin--increased dramatically. With the defeat and relocation of the American Indians, who sided with the British, vast new acreage was opened to settlement. Large numbers of people from other parts of the country, especially the South, began to move northwest and set about clearing the forests and cultivating the land. Many of these emigrants came from Virginia, North Carolina, Tennessee, and Kentucky. One such pioneer was Thomas Lincoln, who, with his family, settled in present-day Spencer County. Thomas Lincoln was attracted to Indiana by the rich land, the absence of slavery, and by the security of the systematic federal land survey, as stipulated in the Land Ordinance of 1785. This legislation passed by Congress opened the area for settlement. Because the land was surveyed by the government before it was made available to settlers, Thomas was able to file a claim on a piece of land and acquire clear title to it. Having lost several farms in Kentucky due to conflicting claims, the prospect of obtaining a clean title made Indiana very attractive.

Thomas Lincoln's son, Abraham Lincoln spent 14 formative years of his life, from the ages of 7 to 21, on a farm in Indiana. He and his family moved to Indiana in 1816 and stayed until 1830 at which time they moved to Illinois. During this period, Lincoln grew physically and intellectually into a man. The people he knew here and the things he experienced had a profound influence on his life. The time he spent on the frontier helped shape the man that went on to lead the country.

Locating the Site

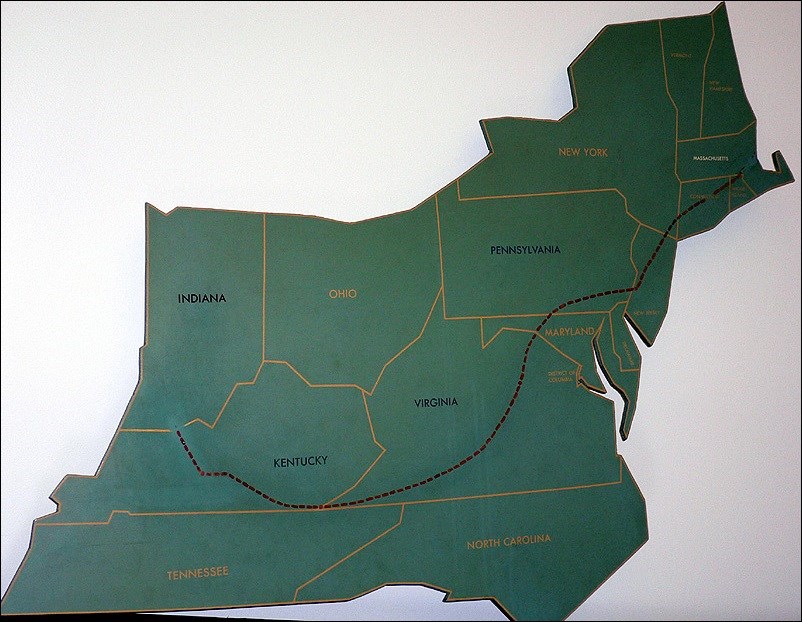

Map 1: Migration route of the Lincoln family.

(Lincoln Boyhood National Memorial)

The Lincoln family, like many others, steadily migrated west with each new generation. Between 1637 and 1816, they settled in Massachusetts, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Kentucky and Indiana. What lured most of them were new opportunities and land. When Thomas Lincoln moved his family north of the Ohio River into the newly formed state of Indiana in 1816, he was continuing a family tradition that had begun several generations before.

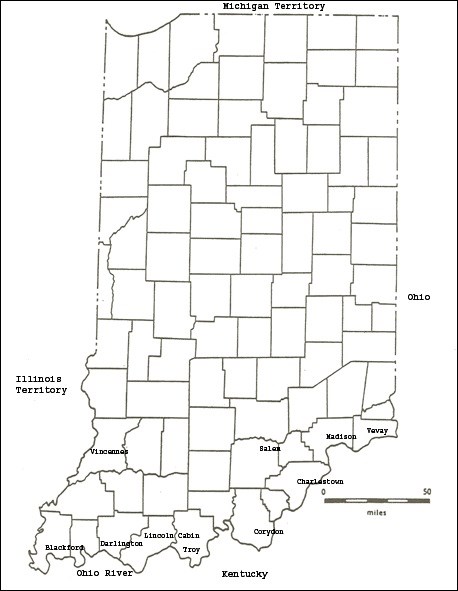

(Lincoln Boyhood National Memorial)

The northern part of the state was unorganized at this time.

Questions for Maps 1 & 2

1. Using Map 1, examine the migration patterns of the Lincoln family. In which direction did they continue to move? Why do you think the Lincoln family kept moving that direction? What are some reasons why families might move to a different part of the country today?

2. Using Map 2, what natural feature determined Indiana's southern boundary? What might have been some reasons frontier families located near this feature?

3. Locate the Lincoln farm. How would you describe its location within the state of Indiana?

4. In what part of the state were most of the towns located at this time? Can you think of any reasons why that might have been?

Locating the Site

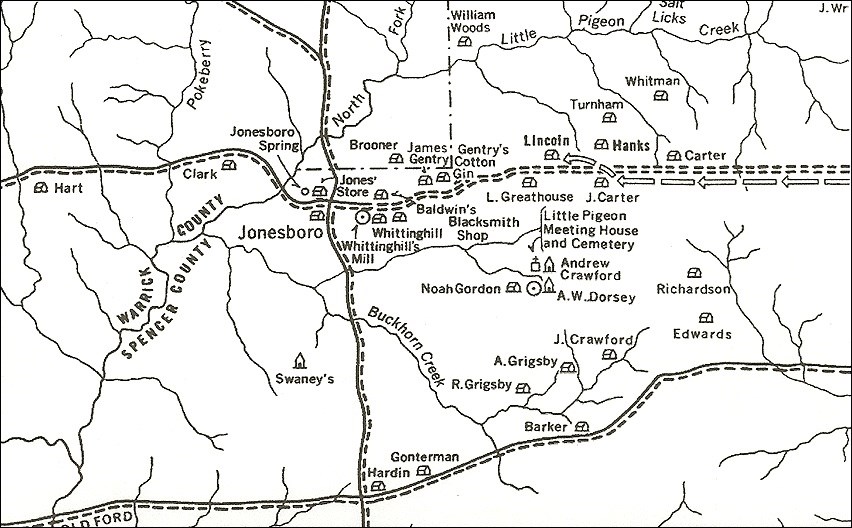

Map 3: The Little Pigeon Creek Community.

(Lincoln Boyhood National Memorial)

Map 3 was created by Lincoln Boyhood National Memorial to represent the Little Pigeon Creek Community circa 1820. There were at least 40 families within a five-mile radius of the Lincoln home in 1820. Most of them had come from Kentucky and some, including the Carters and Gordons, had been neighbors of the Lincolns in Hardin County, Kentucky. These families formed the center of the community within which the Lincolns lived and worked during the 14 years they were in Indiana.

Questions for Map 3

1. Using the scale, how many families lived within a 1½ mile radius of the Lincolns? Make a list of their names.

2. What do you think people used as the primary mode of transportation during the early 1800s? How might transportation and the distance between farms impact social life for the settlers?

3. What other types of businesses and community buildings were in the general area? How far was the closest store from the Lincoln farm? How might this impact the Lincoln's life?

4. How does the community you live in differ from that of the Lincolns'? Are there any similarities?

Determining the Facts

Reading 1: Abraham Lincoln in Indiana

In the fall of 1816, Thomas and Nancy Lincoln packed their belongings and their two children, Sarah, 9, and Abraham, 7, and left their Kentucky home bound for the new frontier of southern Indiana. Arriving at his 160-acre claim near the Little Pigeon Creek in December, Thomas quickly set about building a cabin for his family and carving a new life out of the largely unsettled wilderness. In time, he cleared the fields, improved the cabin and outbuildings, and utilized his carpentry skills to establish himself within the community.

In much of the work his young and capable son assisted. As he grew older, Abraham increased his skill with the plow and, especially, the axe. In fact, in later life he described how he "…was almost constantly handling that most useful instrument…" to combat the "…trees and bogs and grubs…" of the "unbroken wilderness" that was Indiana in the early 19th century. (1)

The demands of life on the frontier left little time for young Abraham to attend school. As he later recalled in a short account of his life, his education was acquired "by littles" and the total "…did not amount to one year." (2) But despite the limitations he faced, his parents encouraged him to learn. Soon, his eyes were opened to the joy of books and the wonders of reading and he became an eager reader. At the age of 11 he read Parson Weems' Life of Washington. He followed it with Benjamin Franklin's Autobiography, Robinson Crusoe, and The Arabian Nights. He could often be seen carrying a book, as well as his axe. For Abraham Lincoln, to get books and read them was "the main thing."

Life was generally good for the Lincoln's during their first couple of years in Indiana, but like many pioneer families they did not escape their share of tragedy. In October 1818, when Abraham was nine years old, his mother, Nancy Hanks Lincoln, died of the milk sickness at the age of 35. The curse of the frontier, milk sickness resulted when a person drank the contaminated milk of a cow infected with the poison from the white snakeroot plant. Nancy had gone to nurse and comfort her ill neighbors and became herself a victim of the dreaded disease by unknowingly drinking some of the contaminated milk. For young Abraham it was a tragic blow. His mother had been a guiding force in his life, encouraging him to read and explore the world through books. His feelings for her were still strong many years later.

Sadly, Thomas and Abraham sawed logs into planks, and with wooden pegs, they fastened the boards together into a coffin for the beloved wife and mother. She was buried on a wooded hill south of the cabin.

The family keenly felt Nancy's absence as young Sarah and Abraham were now without a mother and Thomas without a wife. This loneliness led Thomas in 1819 to return to Kentucky in search of a new wife. He found her in Sarah Bush Johnston, a widow with three children. Thomas chose well for the cheerful and orderly Sarah proved to be a kind stepmother who reared Abraham and Sarah as her own. Under her guidance, the two families became one.

The remainder of his years in Indiana were adventurous ones for Abraham Lincoln. He continued to grow and by the time he was 19, he stood six foot four. He could wrestle with the best and local people remembered that he could lift more weight and drive an axe deeper than any man around.

In 1828, he was hired by James Gentry, the richest man in the community, to accompany his son Allen to New Orleans in a flatboat loaded with produce. While there, Lincoln witnessed a slave auction on the docks. It was a sight that greatly disturbed him and the impression it made was a strong and lasting one. He later commented, "If slavery is not wrong, nothing is wrong. I can not remember when I did not so think, and feel." (3)

Abraham continued to work occasionally for Gentry at his store. He also began to take an interest in politics. The Gentry store was often a gathering place for local residents and there Abraham listened as a number of political views were aired about such topics as internal improvements, tariffs, and presidential candidates. At a young age, he began to form his own opinions and make contributions to the lively discussions, though he was influenced by his father's support of Henry Clay and the Whig political party. The Whig party, which operated in the U.S. from 1832 to 1856, supported the supremacy of Congress over the Executive Branch. The party was ultimately destroyed by the question of whether to allow the expansion of slavery to the territories. Lincoln became a great admirer of Clay and modeled his emerging political beliefs after those of the Kentucky politician. Although they were not to meet for many years, Clay had a profound impact on Lincoln's political development. Many of his positions on issues such as his opposition to slavery and his support of gradually freeing the slaves were adopted and expanded upon by the young politician. In later years, Lincoln referred to Clay as one "whom, during my whole political life, I have loved and revered as a teacher and leader." (4)

Another job that Abraham had during his teenage years was operating a ferry service across the mouth of the Anderson River. In his spare time he built a boat to take passengers out to the steamers on the Ohio. One day he rowed out two men and placed them aboard with their trunks. To his surprise each threw him a silver half-dollar. "I could scarcely credit," he said, "that I, a poor boy, had earned a dollar in less than a day." (5) But he did not get to keep the money since the law stipulated that until he was 21, any money he made belonged to his father.

Although profitable, his business venture also led to one of his first encounters with the legal system. Two brothers, who held the ferry rights across the Ohio between Kentucky and Indiana, charged Lincoln with interfering with their business. Kentucky law, in such cases, provided for the violator to be fined. But, because he did not carry his passengers all the way across the river but only to the steamboats, the judge ruled that Lincoln had not violated the law and dismissed the charge.

By all accounts the Lincolns prospered in Indiana, but in 1830 Thomas decided to move to Illinois. Relatives there had described the soil as rich and productive and that milk sickness, which threatened to break out again in the Little Pigeon community, did not exist. With that news, Thomas sold his property and left the state. He eventually settled in Coles County, Illinois, while Abraham struck out on his own and ended up in New Salem.

Abraham Lincoln lived in Indiana for 14 years, from the age of 7 to the age of 21. During that time he grew physically and mentally. With his hands and his back, he helped carve a farm and home out of the wilderness. With his mind, he began to explore the world of books and knowledge. He experienced adventure and he knew deep personal loss. The death of his mother in 1818 and the death of his beloved sister, Sarah in 1828, left deep emotional scars. But all those experiences made him into the man that he became.

Questions for Reading 1

1. When did the Lincolns move to Indiana? Where did they move from? How many members of the family were there?

2. What caused the death of Nancy Hanks Lincoln? How did her death affect the life of Abraham Lincoln?

3. How do you think Henry Clay influenced Lincoln's presidency? Who were some of the other people that strongly influenced his life?

4. Can you think of someone who has greatly influenced your life? How did that person influence who you are today?

5. How did young Abraham earn money? Did he get to keep the money he earned? How does the amount he made compare with what you might earn today?

6. What impact do you think Abraham's experience with the legal system might have had on his later life?

7. What other experiences do you think influenced him? Can you think of any personality traits or characteristics that Abraham began to develop during his childhood?

Reading 1 was adapted from The Lincoln Notebook, prepared by the staff of Lincoln Boyhood National Memorial.

(1) Autobiography written for John Scripps, June 1860, in Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, Vol. IV. You can visit the entire collection online via the Humanities Text Initiative on the University of Michigan's Digital Library Production Service website at http://www.hti.umich.edu/l/lincoln/.

(2) Ibid.

(3) Letter to Albert G. Hodges, April 4, 1864, in Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, Vol. VII. You can visit the entire collection online via the Humanities Text Initiative on the University of Michigan's Digital Library Production Service website at http://www.hti.umich.edu/l/lincoln/.

(4) Letter to Daniel Ullmann, February 1, 1861 in Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, Vol. IV. You can visit the entire collection online via the Humanities Text Initiative on the University of Michigan's Digital Library Production Service website at http://www.hti.umich.edu/l/lincoln/.

(5) Josiah Gilbert Holland, Holland's Life of Abraham (Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Lincoln, 1998).

Determining the Facts

Reading 3: The Indiana Frontier

For most pioneers, including the Lincolns, the trip west was only the beginning of their new adventure. Once they had reached their destination they had to set about establishing a new home in the middle of an unsettled frontier. The most immediate need was shelter. Often times a temporary structure was put up to protect the family from the elements until a bigger cabin could be built. This was true for the Lincolns during their first winter in Indiana when they lived in a small, hastily constructed log cabin. But at the first opportunity, they began constructing a permanent home. Given the extensive forests that covered much of the land, the log cabin was a natural choice for their dwellings. Logs, often of tulip poplar and about a foot in diameter, were cut to proper size and notched at the ends so corners would be level and secure. Doors and windows were cut in the walls and a fireplace and chimney were built at one end. Clay and mud were used as chinking (filler) between the logs and a roof of wooden shingles topped the structure. Most cabins began with dirt floors; wooden floors were an addition that could wait until later.

The interior of the cabin generally had few furnishings. Most furniture had to be fashioned from natural materials nearby. Beds, stools, tables, chairs, and cupboards were made by the pioneer out of the same trees that he cut to clear his land. Most utensils were also made of wood or of gourds, but there were usually a few items of iron cookware, such as the three-legged spider skillet and a kettle for cooking over the open fire.

Obtaining food to cook over the fire occupied a large amount of the pioneers' time. Hunting was the primary means of obtaining meat for the earliest settlers. Indiana in the early 19th century was rich in natural resources and game was abundant. Deer and bear were initially plentiful and pigeons were reported in flocks so large that they darkened the sky when they flew over. But as the state became more heavily settled hunting became more of a challenge, and the pioneer relied more on agriculture to feed his family. In order for agriculture to be successful, though, the forests had to be cleared. The woodsman's axe was a tool every bit as important as the rifle on the frontier. Trees were either felled or girdled by removing the bark all the way around, causing them to die. Girdled trees could be burned later or left to fall. In the meantime, with the leaves dead, sunshine could reach the crops planted amongst the trees. The timber that was cleared was used for fences, buildings, fuel and other purposes.

Corn was the main crop for the pioneer because it grew easily in the Indiana soil and climate. Thomas Lincoln had, by 1824, 10 acres of corn as well as about 5 acres of wheat and 2 acres of oats. Corn was the basic ingredient in the pioneer's diet, although he did try to supplement it with some garden vegetables such as cabbage, beans, peas, potatoes, onions, pumpkins, and lettuce. Livestock for the typical frontier farm usually consisted of a dairy cow, a couple of horses, some sheep, chickens, and hogs.

Just as they had to provide their own food and shelter, the pioneers also had to make their own clothing. The most common material in the early years was deerskin, which they fashioned into moccasins, shirts and breeches. Later, they used wool and flax, a plant with a long fiber that could be spun into thread and loomed into linen. Wool yarn and linen thread could be woven together to produce linsey-woolsey, a hardwearing, coarse cloth from which most clothes were made. Combing, carding, and spinning wool was a continuous chore for the women and girls.

Life on the frontier was hard and sometimes dangerous. Disease took its toll on many a family. There were fevers of various kinds and occasional outbreaks of such things as cholera and milk sickness, which killed Abraham Lincoln's mother. There were also any number of accidents that could result in injuries like broken bones, deep cuts, and burns. Sometimes these injuries proved fatal. To combat many of these diseases and to try to survive, the pioneers looked to the resources they had on hand and discovered that many of the plants that grew around them could be used as medicines. In this, as in most other areas of their lives, they were forced to do for themselves.

Questions for Reading 3

1. What was one of the most immediate needs of a pioneer family when they settled in a new area?

2. How did the pioneer home and its furnishings compare with your home today?

3. What were the principal sources of food for the pioneers? How did their efforts to acquire food differ from ours today?

4. How and where did the pioneers get their clothes? Where do you get yours? Who makes them?

5. What were some of the dangers faced by the pioneers? What do you see as some threats we face today? Do you think the lives of pioneers were more or less dangerous than ours today?

6. How do you think growing up on the frontier may have affected Abraham Lincoln?

Reading 3 was adapted from The Lincoln Notebook, prepared by the staff of Lincoln Boyhood National Memorial.

Determining the Facts

Reading 4: The Youth of Indiana Becomes the President of the United States

The boy who grew up on the Indiana frontier eventually became the leader of the nation and did so at a critical point in its history. After moving to Illinois, Abraham Lincoln worked at several different jobs before he became a lawyer. His success as a lawyer led him to Springfield, the capital of Illinois, where his long interest in politics became a serious part of his life. In 1834, he was elected to the Illinois House of Representatives where he served three terms. In 1846, he was elected to the United States House of Representatives and in 1858 he ran for Senator from Illinois. Although he lost that election, he gained national prominence, partially through debates with Stephen A. Douglas on the issue of slavery. Two years later, in 1860, he was elected President of the United States, just as the crisis over slavery and secession peaked. Many of the qualities and characteristics that would help him to lead the country through the Civil War were born and nurtured during his formative years between the ages of 7 and 21.

Quotes from Abraham Lincoln:

"In this country, one can scarcely be so poor, but that, if he will, he can acquire sufficient education to get through the world respectably." (1)

" . . . I am never easy . . . when I am handling a thought, till I have bounded it north and bounded it south, and bounded it east, and bounded it west." (2)

Abraham Lincoln's intelligence was invaluable in making the many difficult decisions that came with being President during a time of crisis. He worked hard all his life to educate himself, in spite of many obstacles and challenges, and while President he continued to learn. As a boy he listened to his father and friends talk about the issues of the day, and then worked the idea in his mind until he understood it. His stepmother, Sarah Bush Johnston Lincoln, later recalled that he would repeat things over and over until it was fixed in his mind. As President, he listened carefully to his generals and advisors and read books on military strategy in a continual effort to learn and understand.

"Labor is the great source from which nearly all, if not all, human comforts and necessities are drawn." (3)

"Labor is the true standard of value." (4)

Growing up on the Indiana frontier, Abraham Lincoln learned at an early age that hard work was necessary for survival. He spent long days working with his father to clear the land, plant, and tend the crops. He hired himself out to work for neighboring farmers as a means of bringing additional money in for the family. When he decided to become a lawyer, he read and studied diligently and advised others to do the same. Certainly as President, he knew that it was going to take a lot of hard work to save the Union. He put in long hours attending to the countless details of running the country, including spending the entire night, sometimes, at the telegraph office, waiting for the latest news from his generals. He believed in the virtue of hard work not only for himself but for others. In response to a woman seeking work for her sons in 1865, he forwarded her request to one of his generals with a note stating, "The lady bearer of this says she has two sons who want to work. Wanting to work is so rare a want that it should be encouraged." (5)

. . . resolve to be honest at all events; and if in your own judgment you cannot be an honest lawyer, resolve to be honest without being a lawyer." (6)

Honesty and integrity were character traits that Abraham learned early in life, possibly from observing his father. Thomas Lincoln was described by those who knew him as "a sturdy, honest . . . man." A young and impressionable boy was certainly impressed by the regard with which neighbors and friends held Thomas, and determined to emulate his behavior. Abraham exhibited his own sense of honesty on a number of occasions, enough so to earn him the nickname of "Honest Abe." As a teen, he had borrowed a book about George Washington from a neighbor and while it was in his possession, the book was damaged. Not having any money to pay for the damage, Abraham honestly told his neighbor what happened and offered to work off the value of the book. For three days he worked in the man's fields as payment for the damaged book. Such a strong sense of integrity later became a hallmark of his presidency.

"With malice toward none; with charity for all; with firmness in the right, as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in; to bind up the nation's wounds; to care for him who shall have borne the battle, and for his widow, and his orphan..." (7)

Abraham Lincoln has long been revered for his compassion as so eloquently stated in his Second Inaugural Address. There were also instances of him granting clemency to deserters and of writing heartfelt letters of condolence to bereaved families. Perhaps because he had experienced loss himself at a young age, he was able to empathize with those in pain. But his acts of kindness were not limited to just people. At the age of eight he killed a wild turkey and was so distraught that he resolved never to hunt animals again. A childhood friend remembered that one day at school Abraham ". . . came forward . . . to read an essay on the wickedness of being cruel to helpless animals." Whatever its origins were, the compassion that led him to urge the binding of the nation's wounds, after the terrible devastation of the Civil War, helped ensure the country's survival of its trial by fire.

"I recollect thinking then, boy even though I was, that there must have been something more than common that those men struggled for." (8)

"I hold, that in contemplation of universal law, and of the Constitution, the Union of these States is perpetual." (9)

Abraham Lincoln held very strong beliefs about the sanctity of preserving the Union. In his mind the Founding Fathers envisioned a form of government unlike any the world had ever known and they sacrificed everything to create it. The ideas of freedom, equality of opportunity, and representative government were the foundation upon which a new nation was built. As a young man in Indiana, he read biographies of George Washington and Benjamin Franklin and accounts of the revolutionary struggle they, and others, waged and endured. The impression they left on him was strong and lasting. So much so that when he found himself faced with secession, he did not hesitate, but resolved to preserve the Union. That decision, based on beliefs formed during his youth, significantly impacted the United States of the 1860s, and the United States of today, which still exists due to his resolve.

Questions for Reading 4

1. What are some of the characteristics Lincoln began developing during his time in Indiana?

2. How did these characteristics show up in his life as President?

3. What experiences in your life have left a lasting impression?

(1) "Eulogy on Henry Clay," July 6, 1852, reprinted in Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, v. 2, p. 124. You can visit the entire collection online via the Humanities Text Initiative on the University of Michigan's Digital Library Production Service website at http://www.hti.umich.edu/l/lincoln/.

(2) From an interview with John P. Gulliver of The Independent, March 10, 1860.

(3) From a speech delivered in Cincinnati, Ohio, on September 17, 1859.

(4) "Speech at Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania," February 15, 1861, reprinted in Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, v. 4, p. 212. You can visit the entire collection online via the Humanities Text Initiative on the University of Michigan's Digital Library Production Service website at http://www.hti.umich.edu/l/lincoln/.

(5) From a note sent to Major George D. Ramsay, October 17, 1861, reprinted in Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, v. 4, p. 556. You can visit the entire collection online via the Humanities Text Initiative on the University of Michigan's Digital Library Production Service website at http://www.hti.umich.edu/l/lincoln/.

(6) From "Notes for a Law Lecture," July 1, 1850, reprinted in Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, v. 2, p. 82. You can visit the entire collection online via the Humanities Text Initiative on the University of Michigan's Digital Library Production Service website at http://www.hti.umich.edu/l/lincoln/.

(7) "Second Inaugural Address," March 4, 1865, reprinted in Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, v. 8, p. 333. You can visit the entire collection online via the Humanities Text Initiative on the University of Michigan's Digital Library Production Service website at http://www.hti.umich.edu/l/lincoln/.

(8) Address to the New Jersey State Senate, February 21, 1861, reprinted in Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, v. 4, p. 235-236. You can visit the entire collection online via the Humanities Text Initiative on the University of Michigan's Digital Library Production Service website at http://www.hti.umich.edu/l/lincoln/.

(9) "First Inaugural Address," March 4, 1861, reprinted in Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, v. 4, p. 262. You can visit the entire collection online via the Humanities Text Initiative on the University of Michigan's Digital Library Production Service website at http://www.hti.umich.edu/l/lincoln/.

Visual Evidence

Illustration 1: Lincoln's sum book pages.

(Lincoln Boyhood National Memorial)

Lincoln practiced arithmetic problems in a sum book made of folded paper and stitched in the middle. Historians believe that Lincoln practiced these problems in 1824 when he was 15 years old.

Note the verse in the lower left corner:

Abraham Lincoln

his hand and pen

he will be good but

God knows when

(Lincoln Boyhood National Memorial)

Questions for Illustrations 1 & 2

In Illustration 2, Lincoln assigned himself the problem of multiplying 342,435 by 342. Attempt to solve this problem. Once you have your answer, you can check it just like Abraham checked his. He used a technique called the "Rules of Nines." Follow the directions below.

1. First draw a sizeable X on your paper and put an "A" on the right side of the X, a "B" on the left side, a "C" on top, and a "D" on bottom.

2. What do you get when you add together all the numerals in the multiplicand? Add the numerals in 342,435 or: 3 + 4 + 2 + 4 + 3 + 5.

3. Add together the numerals that make up the multiplier of 342 (3 + 4 + 2).

4. Finally, add up the numerals in your product (the answer you got when you multiplied 342,435 by 342. That's ___ + ___ + ___ + ___ + ___ + ___ + ___ + ____ + ___.

5. What was the number you got when you added up the numerals in the multiplicand? (Your answer for #1) Divide this number by 9. Put your remainder in the big "X" below, right next to the letter A.

6. What did you get when you added up the numerals in the multiplier? (Your answer for #2) Divide that number by 9 and put the remainder in the "X" by the letter B.

7. Now do the same thing with the number you got once you added the numerals in the product. Put the remainder in the top of the "X", next to the letter C.

8. Here are the last three steps. Multiply together the number you put next to A with the number you put next to B. Divide by 9 one last time and put your remainder next to D, in the bottom of the "X."

9. Is the number you put in the top of the "X" (near the C) the same as the number in the bottom of the "X" (near D)? Then your multiplication is correct! Did you get an X that looks like the one by Lincoln?

Visual Evidence

Photo 1: Nancy Hanks Lincoln gravesite.

(National Park Service)

Starting in 1868, there was interest in marking and caring for the gravesite of Nancy Hanks Lincoln. In 1874, a two-foot marker was placed on the site, but with years of neglect it became overgrown with vegetation. In 1897, the Nancy Hanks Lincoln Memorial Association was formed to maintain a site and promote the idea of an Indiana Memorial to the Lincolns. Money was appropriated by the county to buy the 16 acres surrounding the site. In 1902 J.S. Culver resculpted a discarded stone from the Springfield, Illinois monument for Abraham Lincoln's grave and presented it to the Memorial Association. However, after negative reports on the grave's upkeep, the Indiana Governor called for a state commission to care for the 16-acre park in 1907.

Photo 2: Cabin site memorial.

National Park Service.

In honor of Indiana's centennial in 1916, an initiative was undertaken to identify locations important to the state's history. In 1917, Spencer County's centennial commission requested the assistance of older residents of the county in determining the approximate location of Thomas Lincoln's cabin. Twenty such residents assembled on the historic property and pointed to a site they believed to be the location. A marker was erected on the site on April 28, 1917. After deciding that it would be inappropriate to construct a replica of the Lincoln cabin, the state hired architect Thomas Hibben, a native of Indiana, to design this memorial which includes a bronze casting in the shape of the historic cabin sill and hearth surrounded by a stone wall.

For over 30 years, the State of Indiana administered and operated the Memorial--which included the grave and cabin site--to Abraham Lincoln and his mother. In 1962, in recognition of its national significance, Congress authorized the creation of Lincoln Boyhood National Memorial--Indiana's first National Park--to be cared for and interpreted by the National Park Service.

Visitors to the park today can tour the museum and memorial halls, visit the Memorial Building's sculptured panels depicting Lincoln's life from a cabin to the White House, observe pioneer skills demonstrations at the living history farm, and walk the historic Trail of Twelve Stones-commemorating major events in Lincoln's life and career--from the cabin site to the Pioneer Cemetery where Nancy Hanks Lincoln's gravesite rests.

Questions for Photos 1 & 2

1. Do you think it was important for the people of Indiana to mark the grave and cabin site? Why or why not? What value do memorials such as this have to us today?

2. What are some of the strengths and weaknesses of using people's memories to determine a historic site's location? Can you think of any other ways besides relying on people's memories in which the location of a historic site that has been destroyed might be discovered?

3. Why do you think the memorial became a unit of the National Park Service? Do you think it is important to preserve historic sites such as this one? Why or why not? What are some other ways in which the park is telling the story of Lincoln's life?

Visual Evidence

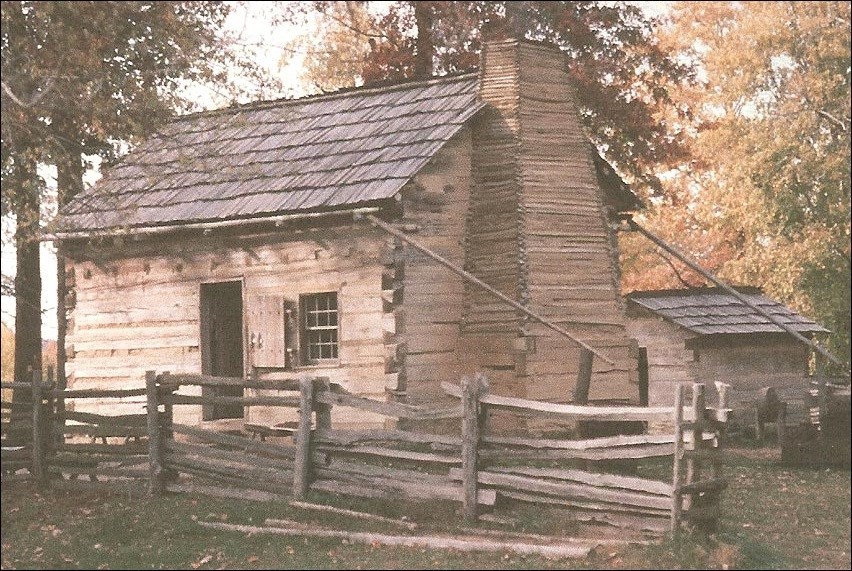

Photo 3: Reconstructed pioneer log cabin.

National Park Service.

The Lincoln Living Historical Farm does not retain any of the original structures from Abraham Lincoln's time. This cabin was built in an attempt to depict a typical farm of his period in Indiana. It incorporates some of what is known of the Lincoln farm and the activities which were a common part of the Lincoln family's daily life. This reconstructed cabin was built as part of the living history component of the park.

Questions for Photo 3

1. The typical pioneer log cabin was approximately 18' x 20' and consisted of one room. What do you think it would have been like for an entire family to live in such a dwelling? What would be some advantages and disadvantages of living in such a manner?

2. How important do you think the fireplace would have been to the pioneers? Why?

3. Preserving food by "smoking" it was a common practice. Meat was hung in a smokehouse where a small fire was built that would create a lot of smoke. The smoke would surround the meat and help preserve it. Can you find the smokehouse in this picture?

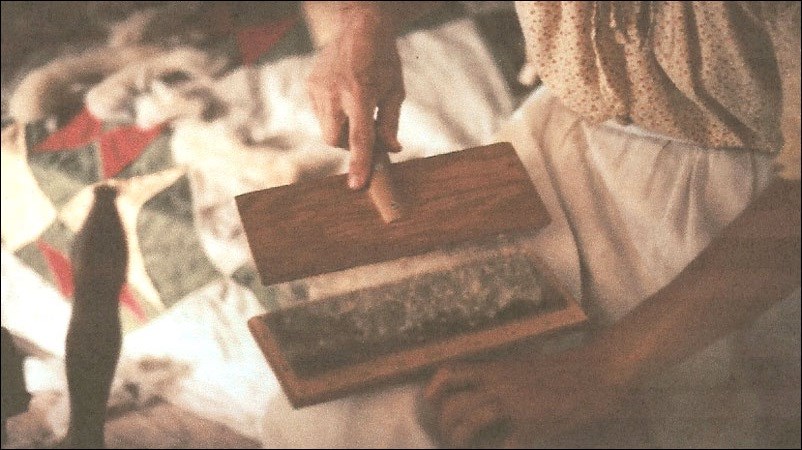

Visual Evidence

Photo 4: Carding wool.

National Park Service.

Wool, as it comes from the sheep, is kinky, matted, and may contain dirt and tangles if it has not been washed. Before it can be spun, it must be gently pulled apart and cleaned. Doing this is called carding. Two paddle shaped wire brushes, called cards, are used.

Photo 5: Spinning wool.

National Park Service.

There were generally two types of spinning wheels used by the pioneers. A small wheel, sometimes called a Saxony wheel, could be used while sitting down; the wheel was moved by pressing down on a peddle with the foot. A larger wheel was often called a "walking" wheel because the person using it had to walk back and forth to keep the wheel spinning constantly.

Wool was often mixed with the fibers of the flax plant to create a type of cloth called linsey-woolsey, which lasted a long time and was used for making everyday clothes.

Questions for Photos 4 & 5

1. What are the names of the tools that are being used in the Photos 4 & 5? What purpose do they serve?

2. What is the purpose of spinning wool?

3. Where did the pioneers get the materials they used for making clothing? Where do you get your clothing today?

4. Who in the pioneer family was generally responsible for the production of clothing?

5. Which of the two types of spinning wheels is being used in Photo 5?

6. Photos 4 and 5 are pictures of some of the activities being done in the park's 1820s living history farm? Do they help you better understand what life would have been like as a pioneer? Why or why not?

Putting It All Together

In this lesson, students meet the people and learn of the events that influenced the development of Abraham Lincoln's character and personality as a youth on the Indiana frontier. The following activities will help them apply what they have learned.

Activity 1: Recreating a Personal Childhood

Abraham Lincoln never wrote his life story so it is impossible for us to know for sure how he felt about his childhood. But now we can see ways in which experiences and people of his childhood influenced things he did as an adult and helped shape his personality and beliefs. Have students reflect on their lives thus far. Have them pretend that they are 77 years old and writing about their childhood. What amusements did they enjoy as young children? How were these amusements shaped by their surroundings? What role has school, neighborhood, and family played in shaping their values? What kinds of things did they learn that helped them in their adult lives? Have students share their "memories" with the class. Emphasize to the class that while our individual experiences may be different, we all share the experience of being shaped by our past.

Activity 2: Abraham Lincoln and U.S. History

Have students check three or four different U.S. history textbooks to see how the authors present Lincoln. What kinds of adjectives are used to describe the man and his accomplishments? How do these adjectives compare with what they learned in this lesson about Lincoln's Indiana childhood? Have students write a short biography of Lincoln's youth using materials provided in this lesson, in U.S. history books, and in books available in libraries.

However, not all people in the U.S. rallied around Abraham Lincoln as President. An alternate activity would be to have students research varying opinions on Lincoln using media sources available to the public during his election, his presidency, and his death. Hold a class discussion that compares and contrasts these varying opinions with what was learned about Lincoln in this lesson. Why do students think Lincoln was such a controversial figure in U.S. history?

Activity 3: Important Figures in Your Local Community

Have students conduct research on an important figure in their own community, preferably one associated with a historic site. Ask students to investigate the following questions and prepare a presentation including visuals on the subject: What did the individual do to achieve distinction? How are the site and the individual related? How and why was the site preserved? If the place no longer exists, what happened to it and when? Would it have helped them understand the person better if the place had survived? If the place still exists, what programs do they offer to learn about the history of the site (for example, the Lincoln Boyhood National Memorial has a living historical farm)? How do they compare to what is being done at Lincoln Boyhood National Memorial (If needed, for more information please visit the park's website at http://www.nps.gov/libo/.)? How might the site improve its interpretation? Have students create posters with photographs, drawings, written information, and/or other materials relating to the subject person and place. Have each student present their findings and then hold a classroom discussion on whether or not students feel it is important to preserve historic sites that are associated with important persons of the past.

Lincoln Boyhood National Memorial: Forging Greatness during Lincoln's Youth--

Supplementary Resources

By studying Lincoln Boyhood National Memorial: Forging Greatness during Lincoln's Youth students meet the people and learn of the events that influenced the development of Abraham Lincoln's character and personality as a youth on the Indiana frontier. Those interested in learning more will find that the Internet offers a variety of interesting materials.

Lincoln Boyhood National Memorial

Lincoln Boyhood National Memorial, a unit of the National Park Service, preserves the site of the farm where Abraham Lincoln spent 14 formative years of his life, from the ages of 7 to 21. Visit the park's website for more information about Lincoln's family and life on the frontier.

Lincoln Home National Historic Site

Lincoln Home National Historic Site, a unit of the National Park Service, has been restored to its 1860s appearance. Visit the park's website for more information about Lincoln's life as husband, father, politician, and President-elect.

Abraham Lincoln Birthplace National Historic Site

Lincoln's Birthplace is a unit of the National Park Service. Visit the park's website for more information about the memorial building at the site of Lincoln's birth.

Abraham Lincoln Historical Digitization Project

Lincoln/Net is the product of the Abraham Lincoln Historical Digitization Project, based at Northern Illinois University. It presents a large multimedia database of primary materials, illustrating life in antebellum Illinois. Search options include "Lincoln's Writings," "The 1858 Lincoln-Douglas Debates," and the "Black Hawk War." There are also resources pertaining to eight major themes in American history: frontier settlement; American Indian relations; economic development; women's experience and gender roles; African-Americans' experience and American racial attitudes; law and society; religion and culture; and political development.

Mr. Lincoln's Virtual Library

Mr. Lincoln's Virtual Library highlights two collections at the Library of Congress that illuminate the life of Abraham Lincoln. The Abraham Lincoln Papers housed in the Manuscript Division contain approximately 20,000 items including correspondence and papers accumulated primarily during Lincoln's presidency. The "We'll Sing to Abe Our Song!" online collection, drawn from the Alfred Whital Stern Collection in the Rare Book and Special Collections Division, includes more than 200 sheet music compositions that represent Lincoln and the war as reflected in popular music. In addition to sheet music, the Stern collection contains books, pamphlets, broadsides, autograph letters, prints, cartoons, maps, drawings, and other memorabilia adding up to over 10,500 items that offer a unique view of Lincoln's life and times.

C-Span's American Presidents Series

In this series, C-SPAN explores the life stories of the men who have been president by traveling to presidential homes, museums, libraries, birthplaces and grave sites, and by speaking with presidential scholars. Included on the website is information about the American President, Abraham Lincoln. [http://www.americanpresidents.org/presidents/president.asp?PresidentNumber=16 ]

The Presidential Papers of Abraham Lincoln

Work on a new, online edition of the presidential papers of Abraham Lincoln officially commenced on November 21, 2001 when Dr. Robert Gruber began reviewing the letters of Union soldiers in the Military Records Division of the National Archives. Gruber is part of a team of research specialists recruited to begin combing the files relating to Lincoln's presidency for what are believed to be a large number of as-yet-undiscovered documents written by or to the Civil War President. When located and transcribed, these will form part of a collaborative project to make all of Lincoln's presidential papers available online by 2009, the bicentennial of President Lincoln's birth. Visit the link to other online collections featuring Lincoln's papers.