National Park Service, C&O Canal National Historical Park

Battles were fought, lives were altered, fortunes were gained and destroyed, and the social fabric of American life was changed forever, particularly around crossroads of transportation such as Manassas, Richmond, and Gettysburg in the east and at Fort Donelson, Shiloh and Vicksburg in the west. The Chesapeake and Ohio Canal, which ran along the Maryland side of the Potomac River, between the Union and the Confederacy, was the focus of much attention.

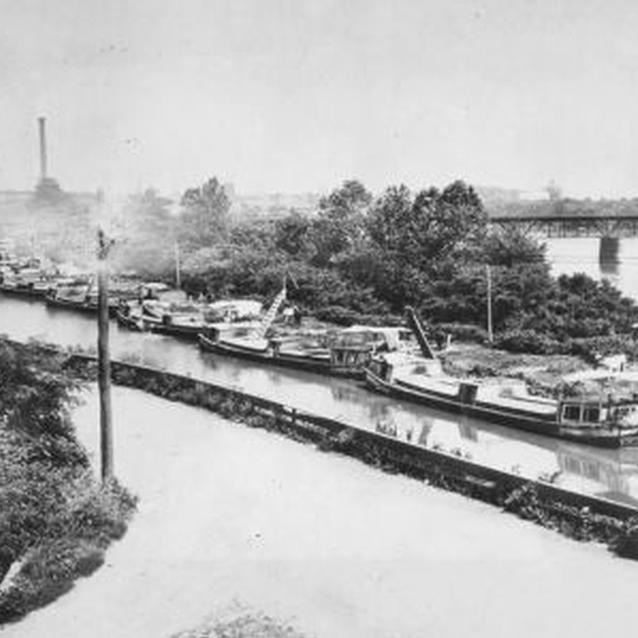

The canal was a lifeline for the Union army. It allowed movement of supplies, troops and ammunition and helped the Union army support its operations in Virginia, West Virginia and Maryland. Despite several attempts by Confederate forces to interrupt the supply line by blowing up aqueducts, setting fire to boats or draining the canal, the canal continued to function. At times, commerce on the canal slowed and in some cases ceased as the war approached its banks, but it always remained in service.

Canals had long been an important part of the economic vitality of the nation. During the Canal Era (1790-1860) much of the nation's prosperity flowed along its waterways. In 1812, four major ports existed - New York, Philadelphia, Baltimore and New Orleans - with 80% of waterborne traffic passing through New Orleans. As canals increased in number, there was an expansion in east-west transportation of goods from the east coast ports into the interior of the country.

In contrast, north-south transportation from the port of New Orleans lagged behind. By 1850 New York had become the largest port in the country. On the eve of the Civil War, 86% percent of canals were north of the Mason Dixon line, helping to tie the newer western states to the east, and bringing into focus the economic and industrial disparity between the North and the South.

By the start of the war, the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal had become a major mover of coal, the fuel of the industrial revolution. Georgetown, for example, was an international port of call until 1859. As a result, coal from western Maryland made its way all over the eastern seaboard, to iron works and foundries that helped to arm the nation, to railways and steamboats that helped transport goods and people.

Library of Congress

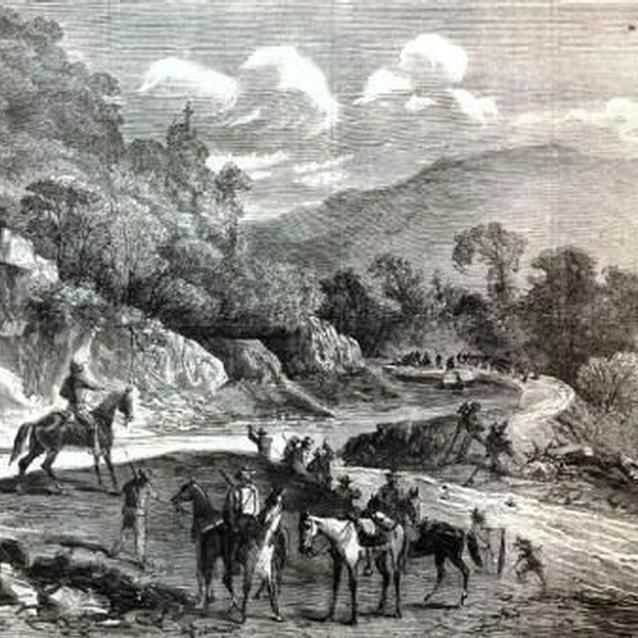

In 1861 things changed. With the outbreak of hostilities, portions of the canal system were in a precarious position. The Chesapeake and Ohio Canal moved supplies to and from the northern Shenandoah Valley, which was vitally important to the Union. The Union established supply bases at Paw Paw, Winchester and Cumberland. The canal aided troop movements by supplementing the railroads that moved men up and down the Potomac River Valley, and provided a passage for civilians trying to get to Harpers Ferry and Sharpsburg after the Battle of Antietam.

Robert E. Lee recognized the value the C & O Canal held for the Union and established a standing order to destroy this artery of commerce and supplies. Confederate Major General Thomas J. "Stonewall" Jackson made several attempts to blow up both the Monocacy and Conococheague Aqueducts, to cause structural damage that would render the canal inoperable. Despite sporadic stoppages, the overall effort failed and the canal continued to operate. Coal continued to be a major source of revenue for the canal, but the movement of government goods and northern military needs held sway. During one scare, the Union army sank over 100 canal boats to block the river and thwart a suspected naval attack by Confederates.

As the war entered its final year, it was becoming evident that the Confederacy's lack of industry and the destruction of its transportation infrastructure helped to play a part in its eventual demise. The Union, however, was still reaping the benefits of coal, supplies and materials being moved via the canal, as it was used in a variety of ways to continue to support the war effort. The canals, roads, railways and waterways of the north were still the economic lifeblood of the nation, and continued to play that role in the decades following the war.

Last updated: September 17, 2020