Last updated: March 5, 2024

Article

Lichens and Air Quality

Lichens are a paradox...durable enough to grow on tree bark and bare rock, yet sensitive to pollution and air quality.

Paul Diederich

Importance

Lichens may look like small plants, but they’re actually composites of a fungus and an algae. The algae in lichens photosynthesize (create food from sunlight energy), and both the algae and fungus absorb water, minerals, and pollutants from the air, through rain and dust.Some sensitive lichen species develop structural changes in response to air pollution including reduced photosynthesis and bleaching. Pollution can also cause the death of the lichen algae, discoloration and reduced growth of the lichen fungus, or kill a lichen completely. Over time, sensitive species may be replaced by pollution-tolerant species. Hence the species of lichens present in a location and the concentration of pollutants measured in those lichens can tell us a lot about air quality.

Inventory

Paul Diederich

- mercury (HG)

- copper (Cu)

- lead (Pb)

- zinc (Zn)

- nickel (Ni)

- cadmium (Cd)

- chromium (Cr)

- sulphur (S)

Some of the plots were located where samples have been collected in the past, some as long ago as the early 1900s.

Results: 45 Lichen Species

Forty-five species of bark-inhabiting lichens were identified during the NCR inventory. Relatively pollution-tolerant lichen communities have developed over time in the region, probably the result of poor air quality in the past century and only slight improvement since. Other outcomes of the inventory are:- NCR’s bark-inhabiting lichen communities are dominated by nitrogen-loving, pollution-tolerant species. Pollution-sensitive species are found infrequently in most parks.

- Lichen communities in urban parks closest to Washington, DC are lowest in species diversity and coverage, and have no pollution sensitive species.

- Lichens in Prince William Forest Park are consistently higher in species richness, highest in coverage of pollution-sensitive species, and lower in element concentration than those from other parks.

- Though moderate variation exists between urban and rural parks, there are no significant pollution “hot spots” in the NCR. Concentrations of sulphur and metals in samples of F. caperata in NCR overall, are not unusually elevated compared to the rest of the U.S. and chromium concentrations are generally low compared to values measured in other studies.

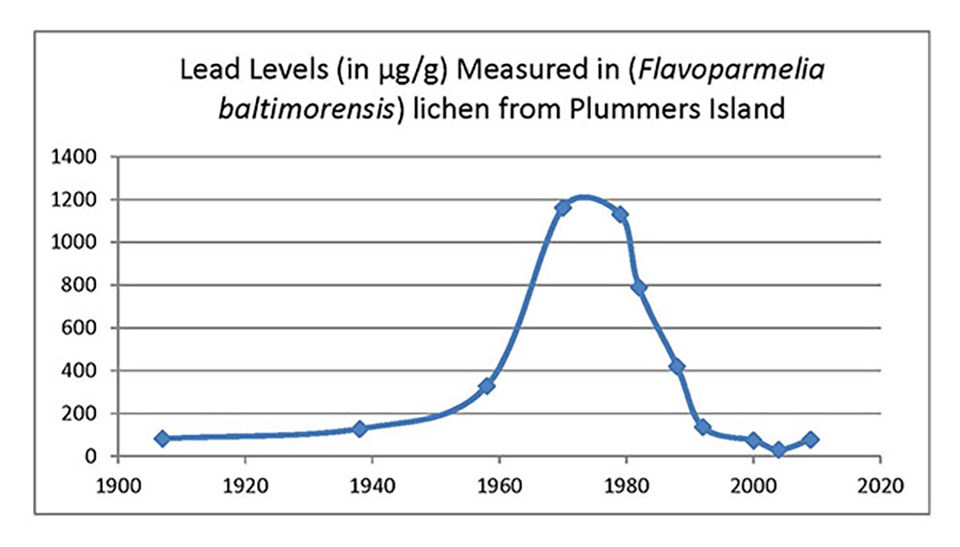

Lead in Lichens

Additionally, present-day lichen communities are far less diverse and contain fewer sensitive species than communities that existed at the same sites in the past century. For example, on Plummers Island, the list of lichens once collected includes many pollution-sensitive species that are no longer found in the mid-Atlantic region.

Learn More

To learn more about how National Park Service scientists are monitoring the health of parks in the National Capital Region, visit the NCRN I&M website.This article is based on material originally published as a resource brief and based on a report by James D. Lawrey:

Lawrey, J.D. 2011. A lichen biomonitoring program to protect resources in the National Capital Region by detecting air quality effects. Natural Resource Program Center, Fort Collins, CO. NRTR NPS/NCRN/NRTR -- 2011/450.

Tags

- catoctin mountain park

- chesapeake & ohio canal national historical park

- george washington memorial parkway

- great falls park

- harpers ferry national historical park

- manassas national battlefield park

- monocacy national battlefield

- national mall and memorial parks

- prince william forest park

- rock creek park

- lichen

- air pollution

- air quality

- lead

- flavoparmelia caperata

- ncrn

- i&m

- plummers island

- nature