Last updated: June 1, 2017

Article

Black Men in Navy Blue: John H. Lawson and William B. Gould

Courtesy U.S. Navy History and Heritage Command

NH 59430

by Polly Kienle, Park Guide

Throughout the four years of the American Civil War, Boston’s Navy Yard at Charlestown built over a dozen ships, converted more than forty, and outfitted an additional twenty-three commercially-built warships in its effort to bring the navy’s fleet to wartime strength. The federal Navy was charged with the vital strategic goal of blockading the Confederate coastline. On the expanding naval enlistment rolls of men called to duty to crew those ships, we find the names of many African Americans. In 1863, roughly 20% of naval enlistees were African American, many of whom shipped aboard the vessels launched at the Charlestown Navy Yard.

The presence of these sailors has its roots in the long history of African American participation in the Atlantic maritime world, while it also bears witness to the struggle of enslaved men to escape their bondage during the chaos that war brought to the slave states. The stories of two such sailors on Boston-built ships, William B. Gould and John H. Lawson, serve to personalize the fight for freedom and opportunity that African Americans undertook in the Civil War Union Navy.

Courtesy of National Museum of American History, Kenneth E. Behring Center.

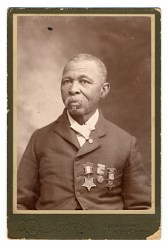

John H. Lawson

A free black man from Philadelphia, Lawson was in his mid-twenties when he enlisted in the Navy at New York in 1863. We do not know what motivated his enlistment two years into the war. His extended family was large and had strong regional roots. Later in life, he supported his family as a small-scale retailer and was active in the Grand Army of the Republic, the North’s Civil War veterans’ organization. Lawson was one of nearly eighteen thousand men (and eleven women) of African descent who served in the U.S. Navy during the Civil War and have been identified by name.

Even before 1861, the Navy – unlike the U.S. Army – had not barred black men from serving. Following the attack on Fort Sumter, African Americans rapidly filled the ranks of the Navy. Within the first ninety days of the War, the representation of African Americans in the Navy had increased four fold. (For more information, USS Constitution Museum has a series of lectures about African Americans in the early U.S. Navy.) Well over a third of the Union Navy’s roughly 17,000 black sailors came from Union states, with Maryland, Pennsylvania, and New York most strongly represented. When Lawson enlisted, he stepped into a milieu that was filled with African American men who had either plied the coastal waters of the Atlantic as commercial sailors or whalers or navigated estuaries and inland river systems stretching from the Great Lakes to the Mississippi Delta. It is not known whether Lawson himself had a maritime background; perhaps he, like still other black sailors he would encounter, was experienced in dockside work but had yet to set sail aboard a ship.

Lawson shipped onto the USS Hartford, a steam screw sloop, just fitted out for wartime service in Philadelphia. The vessel was to become one of the most renowned in the US fleet. Built at the Charlestown Navy Yard in 1858, the Hartford, after serving as flagship of the US Navy’s China fleet, became the leader of the fleet which fought the Battle of Mobile Bay in 1864. During this pitched, three-hour naval battle for control of the Confederate industrial center and port at Mobile, Alabama, Lawson distinguished himself with courageous conduct. When he was awarded the Medal of Honor, his citation read:

[Lawson served] on board the flagship U.S.S. Hartford during successful attacks against Fort Morgan, rebel gunboats and the ram Tennessee in Mobile Bay on 5 August 1864. Wounded in the leg and thrown violently against the side of the ship when an enemy shell killed or wounded the 6-man crew as the shell whipped on the berth deck, Lawson, upon regaining his composure, promptly returned to his station and, although urged to go below for treatment, steadfastly continued his duties throughout the remainder of the action.

Hartford's crew performed in exemplary fashion that day – twelve crewmembers in total were recognized for their actions at the Battle of Mobile Bay with the Medal of Honor, the nation’s highest award. John H. Lawson was one of a total of eight men of African descent to be honored in this fashion for any naval service during the entire Civil War.

This photo originally appeared in the Dec 1917 issue of the NAACP's Crisis magazine. Courtesy of William B. Gould IV.

William B. Gould

At the outbreak of the Civil War, Gould was a literate master tradesman who was enslaved in North Carolina. In September 1862, Gould and seven other men rowed twenty-eight miles down the Cape Fear River to escape bondage, hoping to encounter a Union ship in the coastal waters. The ship he and the others encountered was USS Cambridge, a commercial steamship built in 1860 in Medford, Massachusetts. The Navy purchased Cambridge to bolster the Union Navy’s blockading fleet in July, 1861. At the Charlestown Navy Yard she was converted into a warship, bearing two powerful 8 inch (200 mm) rifled guns. Joining the ship as a “Contraband” sailor with the rank first of "Boy" and then "Landsman," Gould would see the use of Cambridge’s guns during its blockade of Confederate ports and waterways. Though Gould would not have the opportunity to perform with distinction in battle, the initiative he seized in escaping brought about perhaps an even greater impact on his life than the Medal of Honor had on Lawson’s.

“Contraband” sailors were given the lowest ranking the US Navy offered and carried with them the identity of former servitude. The “contrabands” were assigned the manual labor necessary to keep a steam vessel functioning and the busywork considered the foundation of discipline on warships: holystoning, scrubbing, scraping, painting, and polishing. While black men routinely served on gun crews during battle, they stood a far greater chance of serving with small-arms crews, armed with swords, rifles, and pistols, for repelling boarders, and with damage control units, armed with water hoses for dousing fires and battle-axes for cutting away damaged spars and rigging. Small-arms crews consisting of contrabands generally exercised separately from those consisting of white sailors. Despite these disadvantages, Gould was able to use his time in the Navy as a springboard to alter the course of his life.

Perhaps it was while Gould was recovering from the measles at the Chelsea Naval Hospital in Chelsea, Massachusetts, (May – October, 1863), or during his subsequent stint as a crew member on the USS Ohio, a receiving ship docked at the Charlestown Navy Yard, that he began to think that Boston would be a good place to put down roots after the war ended. As a master plasterer, he had career prospects wherever he might go, but Boston offered a small but proud free African American community, as well as proximity to the extended family of Cornelia Williams Read, a childhood acquaintance from North Carolina, now free and living on Nantucket. Through Gould’s extended tour of the Atlantic on the USS Niagara that involved moving between Antwerp, the French coast, and the Bay of Biscay to garner intelligence on Confederate warships being constructed abroad, Gould and Read corresponded. They married on Nantucket in November, 1865, not even two months after Gould was honorably discharged from the Navy at the Charlestown Navy Yard’s muster house. Gould’s chance encounter with the USS Cambridge had brought him, three years later, to the place of its construction, the Charlestown Navy Yard. Gould and his family would settle in the nearby village of Dedham. Though Gould was constrained to only the lowest ranks while enlisted in the Navy, as a member of that arm of the services’ veterans’ organization, the Grand Army of the Republic, he was able to rise to commander of his local post.

Sources & Further Reading:

- Joseph P. Reidy. “Black Men in Navy Blue during the Civil War.” In: Prologue Magazine, Fall 2001, Vol. 33, No. 3. Accessible via the National Archives: https://www.archives.gov/publications/prologue/2001/fall/black-sailors-1.html

- William B. Gould IV. Diary of a Contraband: The Civil War Passage of a Black Sailor (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2002)

- William B. Gould IV, great-grandson of William B. Gould, has created a website that supplements his ancestor’s Civil War diary: http://goulddiary.stanford.edu/

- Barbara A. Gannon. The Won Cause: Black and White Comradeship in the Grand Army of the Republic (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2011)

- Steven J. Ramold. Slaves, Sailors, Citizens: African Americans in the Union Navy (DeKalb: Northern Illinois University Press, 2002)

- Stephen P. Carlson. Charlestown Navy Yard: Historic Resource Study (Boston: National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, 2010)