Latino Workers

This American Latino Theme Study essay explores the role Latino workers have played in the development of labor movements within the U.S during the late 19th and entire 20th centuries as well as their role in the development of the U.S. economy.

by Zaragosa Vargas

The employment experiences of Latinos are as varied as this work force's group histories. Latino workers are made up principally of Mexicans, Puerto Ricans, Cubans, and Central Americans, the latter mostly from Guatemala, Nicaragua, and El Salvador. Latino migration to the U.S. is linked to the demand for labor during periods of economic growth. Beginning in the late 19th century immigration and economic growth became integrally related. The discrimination by employers, Anglo workers, and unions and the U.S. imperial relations with Mexico, Central and Latin America, and the Spanish-speaking Caribbean also frames the history of Latino workers. In spite of hostility, Latino workers since the 19th century have fought for better wages and working conditions through strike actions and have participated in union leadership and struggled to be recognized by labor unions. Latino workerswill continue to have a tremendous impact on America's work force because by 2050 they will constitute one of every three working-age Americans.[1]

Latino Workers in the 19th Century

Nearly two-thirds of Latino workers are Mexican. Their history is underscored by the military conquest of the Southwest by the U.S. and the subsequent colonization and economic development of the region following the Mexican War (1846-1848). Prior to the American conquest, Mexicans in the ranching economies of present Texas and California worked as sheepherders, vaqueros (cowboys), servants, laborers, and artisans. In present New Mexico, small landowners and communal village farmers survived through their own labor. Already by the 1830s in Texas, Anglos out-numbered Mexicans, while Arizona remained relatively abandoned until 1862 owing to marauding Indian tribes. These labor systems during this transition from Mexican rule to U.S. domination were based on debt-peonage. Afterwards, a form of labor relations was ushered in founded on racial inequality and oppression as the worst jobs became synonymous with Mexican jobs. A dual wage system developed based on race that became part of the West's distinct labor relations.[2]

In the late 19th century capital-intensive railroad construction and maintenance, mining, and agricultural expansion unfolded on a massive scale in the Southwest. Mexican labor became the great engine of this region's economic growth and its established working class. Like many other Latinos, Mexicans followed traditional patterns of movement into the U.S. and maintained affiliation with kin and homeland. U.S. immigration policy proved beneficial to employers for it sustained a constant flow of Mexicans into the U.S.; in essence, it institutionalized a revolving door for low-wage workers from Mexico. The Mexican Revolution served as an important push factor in provoking this immigration, but the catalyst triggering Mexican immigration to the U.S. were the labor shortages caused by World War I. During the 1920s a half million Mexican immigrants entered the U.S. Nearly 10 percent of the immigrants made their way to the Midwest where new work opportunities emerged in agriculture, railroad, meatpacking, steel mill, metal foundry, and automobile work.[3]

At the end of Spanish-American War in 1898, the U.S. made Puerto Rico a colony. Puerto Ricans underwent a transition to wage labor with the decline of the plantation system that converted Puerto Rico's economy to large-scale commercial farming for export. The inability of the Island's commercial agricultural economy to absorb Puerto Rico's huge surplus population resulted in double-digit unemployment. To offset mass joblessness, Puerto Rican women entered the labor force in needlework, the mechanized tobacco industry, and other firms dependent on female wage labor.[4]

Puerto Rico's colonial status and its overpopulation problem triggered and sustained outmigration, transforming impoverished Puerto Ricans into proletarian globetrotters who left for work in the Caribbean, Mexico, Latin America, and the Hawaiian Islands. In 1917, Puerto Ricans became American citizens through the Jones-Shaforth Act. Because of the labor shortages of World War I, Puerto Ricans were brought to the U.S. as contract laborers to work on East Coast military bases and munitions factories, on Louisiana sugar plantations, and on Arizona cotton farms. Following the end of Word War I, most Puerto Ricans migrated to New York City and got jobs in commercial, service, needlework, and cigar work. A significant number of Puerto Ricans who settled in the Brooklyn Naval Yard were maritime workers. About 7,364 Puerto Ricans lived in New York City and by decade's end their numbers ballooned to approximately 44,908.[5]

Because of social and economic developments in Cuba after 1865, and the growth of the cigar industry in Key West, Tampa, New Orleans, and New York City, Cuban tabaqueros (tobacco workers) migrated to the U.S. By 1890, 5,500 Cubans lived in Ybor City, and by 1900 this population tripled to more than 16,000. Cuban tobacco workers brought with them a revolutionary nationalism and socialism and a labor organizing tradition steeped in anarchism. Lectores (readers), labor newspapers, and workers' clubs targeted local bosses and the whole system of U.S. imperialist exploitation.[6]

Latino Worker Movements in the Late 19th Century and Early 20th Century

Ignored by organized labor, Latino workers in the 19th century sought support from within their own ranks or from progressive labor movements. Many joined the Holy Order of the Knights of Labor. The first mass organization of the American working class included Latino workers as well as women and blacks because the Knights of Labor made no distinction based on "nationality, sex, creed or color." Mexican Knights of Labor members formed assemblies in Texas, New Mexico, and California. Prominent Mexicans in the Knights included master workman Manuel López of Fort Worth, Texas, and in New Mexico, Juan José Herrera headed the Knights of Labor known as the Caballeros de Labor. Labor organizations in Cuba attempted to coordinate the activities of Cuban workers in the U.S. and sought the cooperation of the Knights of Labor Cuban anarchist Carlos Balino was prominent in the Florida Knights of Labor, forming a chapter of the Knights in Tampa, and in 1886, Balino represented the Knights at its national convention in Richmond, Virginia . As the Knights of Labor declined following the Haymarket Riot of 1886, so did its efforts to enforce the principle of the brotherhood of labor. [7] The demise of the Knights of Labor contributed to the rise of the American Federation of Labor (AFL), formed in 1886 under the leadership of Samuel Gompers. Whereas the Knights of Labor aimed at legislative reforms for all workers such as the eight-hour day, the exclusive AFL focused on protecting the autonomy and established privileges of the craft unions.

During World War I, the AFL adopted a policy of organizing Mexicans, but into separate AFL locals. It assigned Clemente Nicasio Idar as organizer-at-large in Texas and the Southwest. The American Federation of Labor stood firm against immigration from Mexico and its sentiments were made known to U.S. Department of Labor officials. In 1901, the AFL assigned Santiago Iglesias Pantín as a labor organizer for Puerto Rico and Cuba and Iglesias endeavored to organize Latino workers in New York City.[8] The AFL attempted to accommodate skilled Puerto Rican and Cuban tobacco workers. Because of discrimination, the tobacco workers formed the labor caucus La Resistencia in the AFL's International Cigar Workers Union. Puerto Rican and Cuban women worked long hours for extremely poor pay in the tobacco industry in Tampa and New York City and the Puerto Rican anarchist and feminist Luisa Capetillo and other Latina activists demanded that the unions represent them as well.

The AFL could not prevent Latino workers from forming their own unions, which were ethnic based and a defensive reaction to exclusion and victimization. Militant labor activism by Puerto Rican and Cuban workers was an extension of labor activism steeped in socialism and anarchism in Puerto Rico and Cuba, where many had been unionized. Many Mexicans likewise brought radical labor union experience with them to the U.S. Some were members of the anarchist labor federation Del Obrero Mundial (House of the World Worker), followed the anarcho-syndicalist teachings of Ricardo Flores Magón and his Partido Liberal Mexicano (PLM), while others belonged to the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) in Mexico, or joined this anarcho-syndicalist organization in the U.S. Between 1900 and 1920, the IWW recruited Mexicans working in southwestern mines, on the railroads, in construction, and in agriculture and these workers took the lead in many of the era's labor battles. In 1910, Mexican gas workers in Los Angeles, California organized by the IWW struck for higher wages. In 1917, Mexican copper miners in Jerome and Bisbee, Arizona went on strike against the Phelps Dodge Corporation. Organized by the IWW, the miners met opposition from the criminal syndicalist laws passed by Arizona and by several other western states as part of the government's efforts to break the power of IWW unions.

Latino workers would have contributed more to the American labor movement in the early 20th century had U.S. trade unions showed more interest in them. The integration of Latino workers into Anglo-led labor organizations remained limited until the 1930s, when the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) gained acceptance into the American labor movement. The left-wing unions of the CIO genuinely promoted racial equality, supported civil rights, and welcomed both Latino and Latina workers.

Latino Workers in the Great Depression

The economic crisis of the Great Depression was devastating to Latino workers. Union strength among Cuban tobacco workers in Florida declined as cigar factories introduced automatic cigar making machines with women operators and as Havana regained its primacy as the center of cigar manufacturing. Cuban cigar workers began to leave Ybor City for Havana, New York, and elsewhere to find work. Those workers who remained precipitated a general strike in 1931 organized by the Tobacco Workers Industrial Union and the workers once more were brutally suppressed. In New York City, despite high representation in the textile and the garment trades, one of three Puerto Ricans workers could not find work because of prejudice and competition for menial jobs. Consequently, many Puerto Ricans returned to Puerto Rico.[9]

President Roosevelt's New Deal labor legislation, including the Wagner Act of 1935, expanded the role of Latino workers like Bert Corona of the International Longshore and Warehouse Union (ILWU) and Latina women in the International Ladies' Garment Workers' Union (ILGWU) participating in and building the American labor movement. Latinos joined and organized CIO affiliated unions like the ILWU, the United Auto Workers (UAW), and the United Steel Workers of America (USWA), all of which admitted workers for membership regardless of race or ethnic background.[10]

Latina women played a prominent role in the 1930s labor movement, recognizing they shared mutual interests with their male counterparts in gaining higher wages, improved working conditions, and civil rights. Indeed, Latinas were as united as Latino men and were their equals in influence. In San Antonio, Texas labor organizers Emma Tenayuca and María Solís Sager incited Spanish-speaking workers to strike. A veteran of the 1933 walkout by women cigar workers, Emma Tenayuca helped form two locals of the International Ladies Garment Workers Union (ILGWU), and led demonstrations and strikes for New Deal relief work and for the right of Mexican workers to unionize without fear of deportation. Joining the Communist party in 1937, Emma Tenayuca played a central role in the pecan shellers' strike the following year. In 1937 in Chicago, Guadalupe (Lupe) Marshall was active in the expanding labor movement in the city. Lupe Marshall led and participated in the strikers' demonstration at the Republic Steel plant during the infamous "Memorial Day Massacre".[11]

The Popular Front (1935-1939) was a social and political movement that maintained its strength through the language of labor and the newly formed Congress of Industrial Organizations. The open policy of the Popular Front toward ethnic and racial minorities provided Latino workers an avenue for demanding civil rights. The Popular Front in essence was a moment in time when labor rights were civil rights.

Popular Front activities occupied the efforts of Latino workers, like founding the labor and civil rights organization El Congreso del Pueblo de Habla Española (Congress of Spanish-Speaking Peoples) in Los Angeles in 1939. Latinos were also active in support of the Civil War in Spain. In San Antonio, Los Angeles, and Chicago, Mexican Americans raised money and supplies, as did Puerto Ricans in New York City, who in the summer of 1936 staged mass parades to protest the bombing of Madrid. In Ybor City, Cuban American workers who belonged to the Workers' Alliance of America and the Popular Front Committee were similarly immersed in local, national, and international issues.[12]

Latino Workers Organize in the World War II Years

During the World War II years, Latino workers achieved their greatest gains in job and wage advances. This was the result of the nation's wartime emergency need for workers and government intervention in the workplace.[13] Mexican American labor leaders working through the International Union of Mine, Mill, and Smelters Workers Union (Mine Mill) ended the exploitive dual-wage labor system in mining. In California Bert Corona made inroads for Mexican Americans in the ILWU, and CIO Vice President Luisa Moreno brought higher wages to cannery workers through the United Cannery, Agricultural, Packing, and Allied Workers of America (UCAPAWA). On the East Coast, Puerto Rican workers in the National Maritime Union, the Bakery and Confectionery Workers Union, and in Florida, Cuban Americans in the CMIU and the International Hod Carriers and Building Laborers' Union also scored successes.

World War II brought increasing opportunities for Latina women who took jobs in war industries. Mexican American women in southern California obtained work in the aircraft plants and shipyards, while those in the Midwest worked in munitions factories, packing houses, and for the railroads. In New York City, Puerto Rican needle workers made life preservers and military shirts for GIs, and in Tampa, Cuban American women got jobs in the shipyards. By the end of the war, Latina workers were enjoying good wages though many of the jobs they held were low status and would be lost once the war ended.[14]

In 1942, Mexico and the U.S. agreed to establish the Bracero Program, the recruitment and contracting of workers from Mexico. Under the Mexican Farm Labor Supply Program and the Mexican Labor Agreement, approximately 4.2 million Mexican contract laborers entered the U.S. from 1942 through 1964, the majority working in agriculture, with some performing railroad maintenance and repair work. The Bracero Program institutionalized the earlier Mexican migrations as well as stimulated illegal migration to the U.S., with both substituting for each other at different times.[15]At this time, Puerto Rican and Cuban migration increased substantially. Puerto Rican migration was mostly a labor migration. The industrialization program "Operation Bootstrap" in Puerto Rico displaced many Puerto Rican workers, resulting in more than 18,000 Puerto Ricans migrating to the U.S. each year as contract laborers. Puerto Rican migration dispersed from traditional centers in the Northeast to Lorain and Cleveland, Ohio, Gary, Indiana, Chicago, Illinois, Pontiac, Michigan and elsewhere.[16]

U.S. immigration policy after World War II was largely shaped by the Cold War, and many refugees arrived in the U.S. from countries that had fallen into the Soviet sphere such as Cuba. Through the Cuban Refugee Program, 300,000 Cuban refugees were resettled throughout the U.S. to offset the impact of relocation on Miami and south Florida. Many of the refugees took jobs in hotel service, garment, furniture and fixtures making, restaurant, and retail work. Cuban women soon comprised 75 percent of the labor force in Miami's garment industry and were members of ILGWU Local 415. After arriving from El Salvador in the 1950s, Kathy Andrade first worked as a garment worker and organizer in Miami. Moving to New York City, Andrade became the Director of the Department of Education for ILGWU Local 23-25, where she developed bilingual educational and cultural programs for the mostly Latino membership. Andrade became active in the Hispanic Labor Committee, an organization that would soon number 150 Spanish-speaking union officials from AFL-CIO unions, the Teamsters, and the UAW, and later the Labor Council for Latin American Advancement (LCLAA).[17]

Latino Workers in the Postwar Years

The 1947 Taft-Hartley Act impeded union organizing by weakening the National Labor Relations Board and by redbaiting progressive labor activists. These investigations marked the beginning of the post World War II anticommunism that resulted in blacklists, worker dismissals, and the 1949 decision by the CIO to purge communists from its ranks. This did not deter Latino workers from defending their rights. In October 1950 in southeastern New Mexico, the mostly Mexican American members of Mine Mill Local 890 went on a 15 month-long strike against the Empire Zinc Company. The work stoppage known as the "Salt of the Earth" strike took place in the context of the Cold War, and the issue of communism was ever present. Mine Mill had been expelled from the CIO because it was influenced by communism. In January 1952, the sides negotiated a settlement. Latino labor unionism became part of a wider campaign for civil rights after World War II as Latino workers continued to press their demands for justice within unions through various organizations. Despite the Red Scare, Latino workers immersed themselves in party politics; they supported the Community Service Organization, and joined the Independent Progressive Party presidential campaign of Henry A. Wallace. Many Latinos fighting for racial and social equality came under government investigation. In New York City, the House Committee on Un-American Activities (HUAC) investigated labor and civil rights activist and Daily Worker columnist Jesús Colón. In Florida, CMIU Vice President Mario Azpeitia signed a statement sponsored by the Civil Rights Congress deploring the attacks on civil liberties and was similarly investigated by HUAC.[18]

Agribusiness was twice as productive as industry and posed a powerful opponent to labor organization. In 1946, the AFL granted a union charter to the National Farm Labor Union (NFLU) headed by Ernesto Galarza to organize California farm workers. The NFLU struck the Di Giorgio Fruit Corporation, which broke the strike by using local sheriffs and red baiting. Two years later in 1949, the NFLU led 20,000 cotton pickers against the DiGiorgio Corporation in a successful strike over wage cuts. One of the striking cotton pickers was Cesar Chavez, the future head of the United Farmworkers of America. In New York City, Puerto Rican workers were well represented in many industries, and 51 percent of all adult Puerto Ricans were members of labor unions representing hotel, restaurant, laundry, building, and other service sectors. In 1959, two-thirds of all Spanish-speaking households in New York City included at least one person who was a member of a labor union.[19]

In the 1960s, the civil rights movement and the Vietnam War helped to radicalize Latino workers, many who broke into leadership positions in national unions. In 1962, long-time labor and civil rights activist Henry L. Lacayo of North American Aviation in Inglewood, California, was elected President of UAW Local 887, the largest UAW local west of the Mississippi River. In 1963, Lacayo attended Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.'s "March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom," and in 1974, Lacayo became national director of the UAW's political and legislative department. In 1965, farm workers, led by Cesar Chavez and Dolores Huerta, organized as the National Farm Workers of America. It gained union representation in 1970, utilizing marches, community organizing, secondary boycotts, consumer boycotts, and nonviolent resistance. This labor activism inspired farm labor organization in the Texas Río Grande Valley and in the Midwest where the Farm Labor Organizing Committee (FLOC) headed by Baldemar Velásquez signed twenty-two contracts. In 1968, under the auspices of the UAW, 14 labor unions established the East Los Angeles Community Union (TELACU). TELACU applied labor-organizing techniques to housing and urban development. UAW President Walter Reuther assigned UAW unionist Esteban Torres to organize TELACU. Torres was the UAW's director for the Inter-American Bureau for Caribbean and Latin American Affairs. In 1971, Cuban American labor activist Joaquin Otero of the Transportation–Communications Union (TCU) was elected International Vice-President of TCU.

In New York City, because of employer and union discrimination, the Labor Advisory Committee on Puerto Rican Affairs, and later the New York Labor Council, organized Puerto Ricans into unions and encouraged affiliated unions to unionize their Puerto Rican members.[20] Puerto Ricans in the Association of Catholic Trade Unionists, neighborhood community action groups, and other organizations spoke on behalf of Latino workers. Puerto Rican workers joined labor unions, the most important being Hospital Workers Local 1199, or led union locals. In 1967, María Portalatín led other para-professionals in launching an organizing campaign to join the United Federation of Teachers (UFT), a union that had attempted to inhibit the growing electoral strength of the Puerto Rican community. In their first UFT contract, the paraprofessionals won salary increases and a career ladder program. Portalatín became the UFT chairwoman, a NYSUT Board member, and American Federation of Teachers Vice President. Puerto Rican and Latino workers strength was finally acknowledged in 1970, when the New York City Central Labor Council officially recognized the Hispanic Labor Committee, an organization of Spanish-speaking union officials.[21]

Latino Workers in the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s

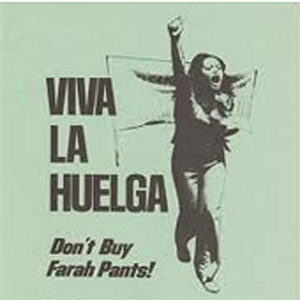

During the 1970s, the Spanish-speaking population nearly doubled from 4.5 to 8.7 million persons, including approximately 1.1 million undocumented Mexicans. Business took an adversarial position against labor at this time, not only forcing union wages downward but launching efforts to break unions altogether. Latino workers did not falter in the face of this employer assault. In 1972, 2,000 female Mexican American and Mexican workers belonging to the Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America at the Farah Pants Company in El Paso, Texas, went on a two-year strike to protest low wages, poor benefits, and unfair treatment by management. The Farah Pants walkout gained nationwide support and triggered a successful consumer boycott of Farah products. In 1975, the UFW won passage of an Agricultural Labor Relations Act (ALRA) that provided for secret elections for farm workers to determine which union the workers wanted to represent them. Facing a range of discriminatory practices, 1,472 Latino workers in Golden, Colorado walked out of the Coors Brewery on April 5, 1977. The Brewery Workers Union representing the workers charged Coors with discrimination and union busting. The Coors Boycott and Strike Support Coalition of Colorado formed to support the striking workers. The Coors boycott continued until 1987, when an agreement was reached between the brewery and its employees.[22]

The fact that Latino workers have never achieved real power in the labor movement was one of the pivotal issues that led to the Latino caucus movement. In April 1973, a group of Latino trade unionists that included 10 international unions and 3 state federations met in Albuquerque, New Mexico and formed the Labor Council for Latin American Advancement. To implement these goals, LCLAA labor leaders such as Cuban American Anita Cofino of Florida worked with the labor movement to encourage voter registration and education among Latino workers, supported economic and social policies and legislation to advance the mutual interests of trade unions and Latino workers, and advocated to ensure equal pay and benefits and union protection for Latino workers.[23]

In the 1980s, America's economic decline greatly impacted Latino workers. The postwar Puerto Rican migration to the northeast coincided with the era's severe drop in manufacturing jobs. New York City experienced the sharpest drop in manufacturing jobs, from over one million in 1950 to about 380,000 by 1987. The largest job loss was in the apparel industry, as dozens of apparel firms relocated to lower cost regions or else moved abroad to take advantage of cheap labor.[24]The continuing restructuring and integration of the Southwest with Mexico greatly impacted Latino workers in this region. In the 1980s, Mexico experienced its worst depression since the Great Depression and, combined with a huge foreign debt and high birth rates, produced a 50 percent underemployment rate at a time when Mexico's labor force grew four times faster than the U.S. labor force. In 1980 in south Florida, another 140,000 Cubans from the Mariel Boatlift arrived and increased Miami's labor force by seven percent in low-skilled occupations and industries. After the Boatlift, Miami received large numbers of Nicaraguans and other Central Americans, a Latino work group that increased 61 percent in this city.[25]

By 1988, one out of every nine Latinos in the U.S. was from Central America, South America, and the Caribbean. Nearly a quarter million Central Americans migrated to the U.S., destined for Los Angeles, Washington, D.C., and New York City. Many Salvadorans and Guatemalans were undocumented because they were not recognized as political refugees but as economic migrants. Central Americans had been activists in their home countries, and in the U.S. became active in the United Farm Workers (UFW) and in El Centro de Acción Social Hermandad General de Trabajadores (CASA). More importantly, members of these worker and immigrant organizations played a prominent role in the Justice for Janitors campaign, in efforts by the Union of Needletrades, Industrial and Textile Employees (UNITE) to organize the garment industry, and in the activities of the Hotel Employees and Restaurant Employees Union (HERE).[26]

In 1986, Congress adopted the Immigration Reform and Control Act (IRCA), regularizing the status of undocumented immigrants and penalizing employers who hired these workers. The law provided that undocumented immigrants, who had been in the U.S. continuously since December 31, 1981, could apply for amnesty. Between 1989 and 1992 under IRCA, some 2.6 million former undocumented aliens gained permanent resident status and could bring in relatives to unify families. At this time, the number of Latinos in the work force increased by 48 percent and began replacing Anglos as the mainstay of the U.S. labor force. About 2.3 million Latinos entered the work force, representing one fifth of the total increase in the nation's jobs, and about 5.3 percent of Latino workers belonged to unions. Latinos took low-wage manufacturing jobs, performed construction, domestic, hotel, restaurant, and other service sector work without union protection and worker benefits. Latino workers continued to experience racial discrimination. In 1989, the AFL-CIO's Organizing Department established the California Immigrant Workers Association (CIWA). Consisting of about 6,000 Latino immigrant members, CIWA's goals were empowering the Latino community through collective bargaining and asserting civil and human rights.[27]

Recognizing the benefits of unionization, Latino workers fought back for labor rights. In 1980 in San Francisco, Latino members of the 17,000-member strong HERE Local 2 organized Latinos Unidos (United Latinos) to support a hotel strike. Miguel Contreras, staff director for HERE Local 2, helped coordinate the twenty-seven day walkout, which produced a significant wage and benefit increase and led to Contreras's appointment as a HERE international representative.

Between June 1983 and December 1985 in southern Arizona, a strike took place against the Phelps Dodge Copper Corporation by Mexican American copper miners and smelter operators in southern Arizona over wage and benefit reductions and the dissolution of the union. Women played a dominant role in sustaining the strike upheaval by picketing, organizing support, and defending their rights even when the Arizona National Guard occupied the mining towns. Latina frozen food workers kept the picket lines active in Watsonville, California. In September of 1985, the Teamsters for a Democratic Union (TDU) organized 1,500 Latina cannery workers who walked out on the two largest frozen food companies in the U.S., Watsonville Canning and Richard A. Shaw Frozen Foods, over successive wage cuts. In the face of court injunctions harassment, and police confrontations, the strike gained national interest. After 19 months of lost wages, half of the strikers returned to work and at a significant wage reduction. In 1989 in New York City, Dennis Rivera, a hospital workers union organizer in Puerto Rico, became Local 1199's President. Under Rivera's leadership, the 78,000 member-strong Local 1199 became the largest union in New York City, gaining good wages, benefits, and working conditions for its members. The Puerto Rican Socialist Party, which developed from the Movement for Puerto Rican Independence (MPI), succeeded in organizing a labor federation independent of the AFL-CIO.[28]

The first largescale breakthrough in the revival of California labor occurred in Los Angeles in June 1990, when Local 399 of the Service Employees International Union (SEIU) forced the international building maintenance company ISS to offer a union contract to 6,000 Latina and Latino janitors in Century City. Known as the Justice for Janitors campaign, it was the largest private sector, immigrant-organizing success since the United Farm Workers' campaign of the 1970s. This strike action was followed by the five month-long strike by Latino drywall workers, which temporarily halted residential construction in downtown Los Angeles by closing down hundreds of building sites. About 2,400 drywallers doubled their wages and unionized when the Carpenters Union negotiated a settlement on their behalf. Latina women also advanced labor's cause. In Los Angeles, María Elena Durazo was elected President of UNITE-HERE Local 11, and built it into one of the most active union locals in Los Angeles County. In 1996, Durazo became the first Latina elected to the Executive Board of HERE.

In 1992, Latino workers comprised 7.6 percent of the U.S. work force mostly in low-paid factory, construction, and other blue-collar work. Many were immigrants. Latino immigrant workers in the 1990s engaged in protests and strike actions to win higher wages and better working conditions and forged a new chapter in the American labor movement. Because unions were reluctant to defend the interests of immigrant workers, Latino workers sought support from within their own ranks, establishing community-based labor organizations such as worker centers to battle worker abuse, anti-immigrant sentiment, and racial discrimination. Latinos soon comprised the largest percentage of new immigrants to the southern states. Latino immigrant workers in the South worked in poultry processing and in meatpacking plants, hotel laundries, construction sites, and agriculture. They fought for job safety, higher pay, and unionization through community-based organizations and union organizing and education initiatives by the United Food and Commercial Workers International Union (UFCW), SEIU, and HERE. As the vanguard of the resurgent labor movement in America, Latino workers linked worker demands with social justice and with the struggles against the transnational corporations in Mexico and the rest of the Americas.[29]

To compete more effectively with Japan and the European Common Market, the U.S. entered into a treaty with Canada and Mexico in 1994 called the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). Free trade through NAFTA sped up the collapse of the living standards of workers in Mexico. In the U.S., NAFTA reordered the American labor force through the influx of workers from Mexico into the expanding low-wage manufacturing, retail, and service sector. The political right attempted to capitalize on anti-immigrant sentiment in the U.S. In 1994, California Republican Governor Pete Wilson threw his support behind Proposition 187 that would have denied public services to undocumented immigrants. The Los Angeles County Federation of Labor (LACFL) joined a campaign to defeat Proposition 187 by organizing a protest of 100,000 Latinos against the anti-immigration proposition. Five years later, in the largest organizing drive since the Great Depression, LACFL helped the SEIU's Local 434B win union recognition for 74,000 home healthcare workers.

Of the more than 10 million Latino workers in the U.S. in the 1990s, 1.5 million belong to the AFL-CIO, representing one of ten union members. Latino union leaders protested to the AFL-CIO about the absence of Latinos on its Executive Council. I n 1995, the AFL-CIO's "New Voice" reform slate called for organizing more minority workers and increasing their presence within labor's leadership ranks. LCLAA member Joaquin Otero had been the only Latino elected to the AFL-CIO Executive Council. The national labor federation failed to bring more Latinos into top leadership positions. This led to the election of long-time unionist Linda Chavez-Thompson as AFL-CIO executive Vice-President in 1995. At its annual convention in 1996, the Labor Council for Latin American Advancement introduced resolutions on stepped up organization of Latinos in the labor movement. As a result, the AFL-CIO committed resources to organize industries employing Latino, immigrant, and other minority workers. María Elena Durazo remained an active participant in shaping recent Latino labor history that involved powerful movements for social, political, and economic equality and justice for workers. In 2004, Durazo became Executive Vice President of UNITE-HERE International, and in 2006 he was elected as Executive Secretary-Treasurer of the Los Angeles County Federation of Labor, AFL-CIO.[30]

Latino workerbased political representation increased rapidly. In 1997, LACFL endorsed Gilbert Cedillo, general manager of SEIU Local 660, for a California state assembly seat from the heavily Latino downtown district of Los Angeles. In 2002, Fabian Núñez, former political director of the LACFL, was elected to the California State Assembly. Núñez later became speaker of the California State Assembly. Key to these pro-labor political successes was the creation of the Organization of Los Angeles Workers (OLAW) by Miguel Contreras, María Elena Durazo, and SEIU International Vice President Eliseo Medina. OLAW trained union members from HERE, UNITE, and SEIU to campaign on behalf of prolabor candidates in specific districts through the use of phone banks, precinct walking, and advertising in the immigrant press. OLAW also got support from the Coalition for Humane Immigrant Rights of Los Angeles (CHIRLA), CASA, Clinica Romero (a Salvadoran immigrant solidarity organization), and a number of Mexican and Guatemalan hometown associations. Similar Latino worker-based political activity unfolded in the Midwest, the Northeast, and in South Florida.

The AFL-CIO and the breakaway labor federation "Change to Win" developed pro-immigrant policies, finally recognizing that they would have to organize immigrant workers in low-wage service jobs if the national labor federation were to survive. A number of the largest international unions–including the SEIU, UFCW, and the garment and hotel/restaurant amalgam UNITE HERE–had substantial numbers of Latino immigrants as members. Latino labor organizations, union caucuses in AFL-CIO affiliates and central labor councils, and immigrant worker associations and centers brought attention to low wages, workplace discrimination and anti-immigrant nativism, and underrepresentation in the labor movement. The resurgence of Latino labor in the U.S. marked an important turning point for labor, and it was shaping the way labor unions relate to the larger Latino community.[31]

Latino Workers in the Contemporary Era

In 2000, 32.8 million Latinos resided in the U.S. and represented 12 percent of the U.S. population. Three years later in 2003, the Latino population totaled 37 million, or 13 percent of the U.S. population. The SEIU's Justice for Janitors strike in 2000 foreshadowed the broad support for immigrant rights that unfolded in March and April 2006, when millions of Latino immigrant workers nationwide protested against repressive immigration reform proposals and to demand the right to work and live in the U.S. with the option of becoming U.S. citizens. These mass worker demonstrations constituted a new civil rights movement in America.

Contemporary Latino immigration remains a "Harvest of Empire," a result of the U.S.'s historic military intervention, support for dictators, and its free trade economic policies that have wreaked havoc in the Americas. Many Latin American countries struggle to comply with the conditions placed by the International Monetary Fund on their massive foreign debt and to cope with the economic upheavals associated with free trade. As governments devalue their currency and decrease spending on education, health care, and food subsidies and as domestic industries are further undermined by international competition, more and more Latin Americans will seek work in the U.S., despite the great dangers in crossing the border.[32]

The more than 50 million Latinos comprise nearly 16 percent of the U.S. population, the nation's largest minority group. They remain a large and growing part of the U.S. labor force. There are about 19.4 million Latino workers and they comprise 12.2 percent of the nation's unionized work force. The workers, both men and women, are concentrated in highly unionized service sector industries like health care, government, communication, and transportation. Discrimination and nativism continue to work against Latino workers, who in the new millennium have experienced the sharpest drop in employment and the weakening of union protections. Undocumented Latino workers fare the worst; they are overrepresented in the lowest-skilled and most dangerous jobs, have the highest levels of wage theft, and death and injuries at work. Given America's economic trade policies such as NAFTA and CAFTA and the nation's addiction to cheap labor, the absence of a path to legalization exposes undocumented workers to labor, human, and civil rights' violations and anti-immigrant legislation at the state and federal level. The labor movement remains the most important source of protection for undocumented workers.[33]

The U.S. has yet to come to terms with its Latino past. Additional national historical sites, monuments, or memorials are needed to recognize the history-making power of Latino workers who have been an integral part of the U.S. work force and are greatly expanding its diversity. To designate places heretofore unrecognized for preservation and honor would celebrate the numerous contributions of Latino workers in the building of America and would be an official expression of integrating Latinos in our nation's heritage.

Zaragosa Vargas, Ph.D., is the Kenan Eminent Professor in the Department of History, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill. He specializes in Latino history and American labor history during the 19th and 20th centuries that covers working class history; work, race, gender, and class; the history of working women; and transnational labor migration. His major works include Crucible of Struggle: A History of Mexican Americans from the Colonial Period to the Present Era; Labor Rights Are Civil Rights: Mexican American Workers in Twentieth-Century America; and Proletarians of the North: Mexican Industrial Workers in Detroit and the Midwest, 1917-1933. He received his Ph.D. in History from the University of Michigan.

Endnotes

[1] Hector E. Sánchez, Andrea L. Delgado and Rosa G. Saavedra, Latino Workers in the United States 2011. Labor Council for Latin American Advancement, Washington, D.C. 2011, 9, 15; Peter Cattan, "The Diversity of Hispanics in the U.S. Work Force," Monthly Labor Review, Vol. 116, no. 8 (August 1993), 1, 13.

[2] Gregory De Freitas, Inequality at Work: Hispanics in the US Labor Force (New York: Oxford University Press, 1991),15.

[3] DeFreitas, Inequality at Work, 15-16.

[4] DeFreitas, Inequality at Work, 28; Virginia Sánchez-Korrol, From Colonia to Community: History of Puerto Ricans in New York City, 1917-1948 (Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 1983), 20-26. In 1920, one-fifth of the Puerto Rican labor force was unemployed, and the high jobless rate continued; in 1934, one third of Puerto Rican workers were without work.

[5] Sánchez-Korrol, From Colonia to Community, 9-20, 28-29, 94-95, 109; DeFreitas, Inequality at Work, 34.

[6] Gerald E. Poyo, "Cuban Communities in the United States: Toward an Overview of the 19th Century Experience," in Miren Uriarte and Jorge Canos Martínez, Cubans in the United States (Boston, MA: Center for the Study of the Cuban Community, 1984), 44-64.

[7] Robert J. Rosenbaum, Mexicano Resistance in the Southwest: "The Sacred Right of Self-Preservation" (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1981), 124; Gerald E. Poyo, "With All, and for the Good of All": The Emergence of Popular Nationalism in the Cuban Communities of the United States, 1848-1898 (Durham: Duke University Press, 1989), 74.

[8] Eddie González and Lois S. Gray, "Puerto Ricans, Politics, and Labor Activism," Cornell University ILR School, 1984, 118.

[9] DeFreitas, Inequality at Work, 16-17; Sánchez-Korrol, From Colonia to Community, 31-32.

[10] D. H. Dinwoodie, "The Rise of the Mine-Mill Union in Arizona Copper," in James C. Foster, editor, American Labor in the Southwest: The First One Hundred Years (Tucson: The University of Arizona Press, 1982), 46-47.

[11] Sarah Deutsch, No Separate Refuge: Culture, Class, and Gender on an Anglo-Hispanic Frontier in the American Southwest, 1880-1940 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1987), 166, 173-174.

[12] Albert Camarillo, Chicanos in California: A History of Mexican Americans in California (San Francisco: Boyd and Fraser Publishing Company, 1984), 58-63; Sánchez-Korrol, From Colonia to Community, 187-190, 197-199.

[13] Threatened by a mass march by African American labor leader A. Philip Randolph in 1941, President Roosevelt issued Executive Order 8802, ending discrimination in federal hiring and by manufacturers holding government defense contracts, and created a Committee on Fair Employment Practices (FEPC) to investigate complaints of racial discrimination.

[14] Nelson Lichtenstein, Labor's War At Home: The CIO in World War II (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1982), 111; Altagracia Ortiz, Puerto Rican Women and Work: Bridges in Transnationa Labor (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1996), 59.

[15] At its height in the 1950s, the Bracero Program coincided with Operation Wetback, a military-style operation that apprehended 865,318 Mexicans in 1953 and 1,075,168 in 1954.

[16] Sánchez-Korrol, From Colonia to Community, 33-36, 40, 46.

[17] González and Gray, " Puerto Ricans, Politics, and Labor Activism," 122-123.

[18] Several blacklisted Hollywood filmmakers made a film about the strike after it was over, but the film was suppressed because of the anticommunist sentiment prevalent at the time.

[19] H.L. Mitchell, "Little Known Farm Labor History, 1942-1960," in James C. Foster, editor, American Labor in the Southwest: The First One Hundred Years (Tucson: The University of Arizona Press, 1982), 116-118; González and Gray, "Puerto Rican Politics and Labor Activism," 118.

[20] González and Gray, "Puerto Ricans, Politics, and Labor Activism," 120.

[21] Sánchez Korrol, From Colonia to Community, pp. 199-200; González and Gray, "Puerto Ricans, Politics, and Labor Activism," 120.

[22] Nancy MacLean, Freedom Is Not Enough: The Opening of the American Workplace (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2008), 177-179 In late 1978, Coors took back three fourths of the strikers and hired new employees to replace the rest.

[23] González and Gray, "Puerto Ricans, Politics, and Labor Activism," 120-121.

[24] DeFreitas, Inequality at Work, 140, 142.

[25] Ibid., 256; Cattan, "The Diversity of Hispanics in the U.S. Work Force," 3, 5-7.

[26] Elizabeth G. Ferris, The Central American Refugees (Westport, Connecticut: Praeger Publishers, 1987), chaps. 2 and 7.

[27] Mike Davis, Prisoners of the American Dream. Politics and Economy in the History of the US Working Class (New York: Verso Books, 1986), Sánchez, Delgado, and Saavedra,Latino Workers in the United States, 2011, 11.

[28] When Rivera left Local 1199 in 2007, it had nearly 300,000 members.

[29] Cattan, "The Diversity of Hispanics in the U.S. Work Force," 9, 12.

[30] Kim Moody Workers in a Lean World: Unions in the International Economy (New York: Verso, 1997), 161.

[31] Ruben G. Rumbaut Origins and Destinies: Immigration, Race, and Ethnicity in Contemporary America," in Sylvia Pedraza Bailey and Ruben G. Rumbaut, eds., Origins and Destinies: Immigration, Race and Ethnicity in America> (New York: Wadsworth Publishing, 1996), 39-40.

[32] Juan Gonz<ález, Harvest of Empire: A History of Latinos in America (New York: Penguin, 2000).

[33] Sánchez, Delgado, and Saavedra, Latino Workers in the United States, 2011, 11-12, 15.

The views and conclusions contained in this document are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as representing the opinions or policies of the U.S. Government. Mention of trade names or commercial products does not constitute their endorsement by the U.S. Government.

Part of a series of articles titled American Latino/a Heritage Theme Study.

Last updated: July 10, 2020