Coming Home to Salsa: Latino Roots of American Food

This American Latino Theme Study essay explores the history of Latino foods in the U.S. in the 19th and 20th centuries and their growth and popularity in the U.S. food industry

by Jeffrey M. Pilcher

Latino foods are the historical product of encounters between peoples from many lands. Some of these meetings took place in the distant past; for example, Spanish settlers and missionaries were exchanging foodstuffs and recipes with Indian women in New Mexico and Florida decades before the first Pilgrim Thanksgiving at Plymouth. Other encounters have been more recent, as with the arrival of Afro-Caribbean and Chinese-Cuban migrants to New York City, who imparted Latino influences to the "soul food" of the Harlem Renaissance in the 1920s and 1930s. Latino foods thus grew out of the migrations of diverse people from the Americas, Europe, Africa, and Asia. Their history has been shaped by the common experience of Iberian culture that spread widely in the centuries after Columbus. But despite these global trajectories, Latino foods have taken root in particular places and nourished communities of people in the territory that is now the U.S. This nation and its foods are products of the fusion between the global and the local, and Latinos form a significant chapter in that history.

Economic imperatives have been a central driving force in the emergence of new cuisines. Columbus first landed in the Americas while searching for spices, and many Latino foods took shape during a regional economic boom of the late eighteenth century. In a similar fashion, Mexican American cooking was influenced by the availability of new ingredients from the U.S. food processing industry. Moreover, many of the leading agricultural industries in the U.S. have Latino origins. Spaniards planted citrus and nut orchards in Florida and throughout the Southwest, founded cattle ranches in Texas, and built wineries in California. The "three sisters" "maize, beans, and squash "staples of the American Indian diet, were domesticated in what is now Mexico. Markets and restaurants are important centers of culinary innovation, particularly as tourists seek out new dining experiences. By the 1990s, Mexican food became one of the top three varieties of ethnic restaurants and salsa (a spicy tomato-based sauce) famously surpassed catsup as the bestselling condiment in the United States.

Changing fashions for Latino food also reflect shifting ethnic and national identities. Despite their long history and contemporary popularity, Latino foods were seen as foreign and dangerous by earlier generations, many of whom defined "American" food narrowly as the product of New England kitchens. The strong flavors of chile peppers, garlic, spices, and olive oil came as a shock to prim palates accustomed to boiled meat and potatoes with white sauce. Encounters of the 19th century, framed by the U.S.-Mexican War and subsequent conflicts over land, left enduring stereotypes of Latina women as eroticized and dangerous, just as their cooking became associated with "Montezuma's revenge." Attitudes toward spicy foods therefore became associated with patterns of racial thinking that worked to exclude Latinos from full citizenship. Nevertheless, businessmen sought to profit from widespread interest in these foods by selling chili powder, canned tamales, and other ersatz products, which advertisers claimed were more wholesome than the originals. After decades of canned chili, many people did not even recognize the Mexican roots of chili con carne (chili with meat). The arrival of fast food restaurants took Latino foods even further from their ethnic roots. Only the spread of migrant family restaurants across the U.S. in the final decades of the 20th century has started to reclaim Latin American cooking from these stereotypes.

The encounters that have shaped ethnic foods, while centered largely in the marketplace, took place at many levels. Often times cross-ethnic eating also crosses lines of class; whereas early 20th century Bohemian diners went slumming in Spanish restaurants, today they are more likely to patronize taco trucks. Yet historically, culinary cosmopolitanism has been just as likely to emerge from within the lower classes. Single, male migrant workers have long sought out tasty and economical meals with little regard for ethnic origins. Cooks likewise are constantly exchanging recipes with their neighbors, whether they were born across the street or across the world. Successive waves of migration have given the U.S. a diverse and innovative food culture.

Yet narrow views of Latino foods as being only Mexican or Tex-Mex are a pervasive misunderstanding. Although the term Tex-Mex has been used commonly as a marker of inauthentic foods, it more properly refers to the regional cooking of Mexicans living in Texas. Such borderland specialties as carne asada (grilled beef) and wheat flour tortillas established the initial images of Mexican food in the U.S. More recent migration has introduced a much wider range of recipes from throughout Latin America. Restaurant goers with a taste for carne asada can also sample the diverse cuts of grilled meat that are called parrilla in Argentina and Uruguay or churrasco in Brazil. Connoisseurs likewise have learned to distinguish the regional tamales of Mexico and the Caribbean basin, not to mention Bolivian, Ecuadoran, and Peruvian humintas (baked corn tamales), Salvadoran pupusas (stuffed tortillas), Venezuelan and Colombian arepas (maize griddlecakes), and countless other dishes that are now available in the U.S.

Because of its emotional bonds, food has been a metaphor for citizenship. The melting pot formerly symbolized the process of immigrant acculturation to the national culture. More recently, the image of a salad bowl in which ingredients are combined without losing their character has gained favor to indicate the acceptance of cultural diversity within a pluralistic democracy. Nor are these culinary metaphors exclusive to the U.S.; in Latin America, as well, foods have provided ethnic and racial markers. In Cuba, for example, the combination of black beans and rice is referred to as moros y cristianos (Moors and Christians). Cultural contact inevitably results in blending, as cooks incorporate the foods of their neighbors into their own culinary repertoires and thereby transform those dishes. Whatever the preferred metaphor, food has an important role in achieving the ideal of cultural citizenship, the belief that all people have the right to determine their own cultural practices.

Latino foods reflect the enormous social diversity resulting from Latin America's history of settlement and intermarriage. The indigenous inhabitants of the Americas domesticated three highly productive and nutritious staples: corn, potatoes, and manioc, which are now eaten widely around the world. Iberian conquistadors introduced to the region the Mediterranean cuisine of wheat, wine, and olives, along with livestock. Subsequent histories of migration further enriched these cuisines, as African slaves, Asian indentured servants, and Middle Eastern arrivals brought new flavors and culinary techniques. The regional cuisines of Latin America demonstrate the everyday genius of cooks in transforming often-limited ingredients into tasty and nutritious meals.

Maize, a sturdy grain that grows prolifically in diverse climates and terrains, was the dietary staple of Mesoamerica, the densely populated cultural region extending from the central highlands of Mexico through Central America. Because maize is deficient in niacin, cooks discovered an alkaline treatment process to make nixtamal, which could be eaten as a stew called pozole or ground into dough to make tortillas and tamales. Pueblo Indians of the Southwest made a thin nixtamal batter and cooked it into thin blue wafers of piki bread on a heated stone. Yet another version of nixtamal, called hominy, was invented independently near Cahokia in Illinois, and allowed the Woodland Indians to spread across eastern North America. Indigenous peoples of the Caribbean and South America also ate corn, but because it was less central to their diet, they had no need to prepare nixtamal. They simply popped the corn, grilled it on the cob, or, in the Andes Mountains, brewed it into an alcoholic beverage called chicha.

Potatoes and related root crops are grown in thousands of varieties in the Andes, in contrast to the meager selection found in U.S. supermarkets. They generally come in two varieties, sweet and bitter, and both are well-rounded nutritionally, with protein, carbohydrates, vitamins, and minerals. The indigenous people learned to freeze-dry potatoes, taking advantage of night frosts and sunny days, a process that also made bitter potatoes more edible. Other tubers added variety to the diet or were cultivated in extreme mountain environments where ordinary potatoes would not grow. The sweet oca, for example, could be dried into a fig-like substance to sweeten dishes. Andean Indians ate the greens as well as the roots of many species.

Manioc, also known as cassava and yucca, was the staple food of the Caribbean and South American lowlands. Like other root crops, there were sweet and bitter varieties. Sweet manioc grows quickly and can be eaten without elaborate preparation, but it is susceptible to rotting. The bitter variety, which can be stored underground for lengthy periods, contains prussic acid that must be removed before consuming. The Indians learned to grate the root, soak away the toxic chemicals, and then bake the resulting pulp into flat breads on a griddle. Alternately, the processed manioc could be dried into a coarse meal called farofa, which is used widely in Brazil to thicken stews and to add a tasty crust to meats and vegetables.

Indigenous peoples domesticated a wide range of other plants in addition to these basic staples. Frijoles (beans) added protein to native diets, especially when eaten with maize; the complementary amino acids within the two foods magnified their nutritional value. Native fruits and vegetables included tomatoes, squash, avocados, cactus paddles and fruit, pineapple, papaya, guava, and mamay. Chile peppers and achiote seeds added flavoring to an otherwise starchy diet, as did chocolate and vanilla which were also domesticated in the Americas. Although their diets were largely vegetarian, Native Americans also consumed many different kinds of fish and game.[1]

If the indigenous cultures gave local variety to Latino foods, Iberian traditions provided a measure of continuity across the region. Wheat, wine, and olive oil, staples of the Mediterranean diet since antiquity, were eagerly planted by settlers and missionaries wherever possible. This desire to reproduce European foods was driven not only by a desire for familiar tastes, but also by social and religious imperatives. Food was an important status marker in the hierarchical society of early modern Europe and conquistadors were determined to eat like nobles back home. When particular environments were not conducive to growing foods, for example, wheat in the Caribbean, the settlers paid great sums to import the grain from elsewhere. Moreover, the Mediterranean culinary trinity was essential for religious sacraments; according to medieval Catholic doctrine, only wheat could be used to prepare the Eucharist.[2]

European settlers also transplanted livestock to the Americas to ensure access to meat and cheese. Sheep was the most highly valued livestock in the Iberian peninsula, a reflection of Jewish and Muslim dietary influences during the Middle Ages. While wealthy Spaniards ate mutton, the lower classes consumed beef from the vast cattle herds of Castille and La Mancha. Horse-mounted cattle ranching skills were carried from Spain to the gauchos of Argentina and Uruguay as well as the vaqueros of northern Mexico. European livestock reproduced at a tremendous rate in the plains of the Americas, since there were few predators and little competition from humans or other herbivores. Because the animals roamed with little supervision, except during annual roundups, they had a tendency to overgraze the landscape, causing widespread erosion, and in many places they converted fertile grasslands to scrubby deserts.[3]

The role of Franciscan missionaries in establishing California's wine and olive industry is well known thanks to the efforts of historic preservationists, who sought to encourage tourism in the early 1900s with picturesque images of a Spanish pastoral era. Nevertheless, the work of ordinary settlers in making wine throughout the southwest has gone largely unrecognized. El Paso del Norte, present-day El Paso, Texas, for example, was praised by visitors for the quality of its wines. Both friars and settlers planted an Andalusian grape variety known as the mónica. Fortified sweetened wines, similar to Spanish sherry, became known in California as Angélica.

In addition to Native American and Iberian traditions, Latino foods bear tastes from around the world. African slaves were imported to work on plantations in tropical lowlands of the Caribbean, Brazil, and along the Pacific. Many of the inhabitants of those regions still have a taste for starchy main dishes of plantains, rice, yams, or couscous, and flavored with greens, okra, malaguetta peppers, and palm oil. Middle Eastern influences are also apparent in the wealth of sweetened desserts, including flan and other custards, which were reproduced in the convents of Latin America. The presence of complex spice mixtures in dishes such as Mexican mole sauce as well as pickled dishes known as escabeche also derived from medieval Arabic cooking. Finally, Asian tastes arrived by way of the colonial Manila Galleon, which traversed the Pacific each year carrying silver and other trade goods between Acapulco and the Spanish colony of the Philippines. Nineteenth-century plantation owners employed indentured servitude after the abolition of the African slave trade, thereby reinforcing Asian culinary traditions with stir-fries and curry sauces.

Latin America became a hub of globalization during the early modern era through a process that has been called the Columbian exchange. Although Iberian settlers preferred European foods, particularly wheat bread and meat, they acquired a taste for many indigenous foods, including frijoles, chile peppers, and chocolate. Cultural mixture, known in Spanish as mestizaje, has become so complex in Latin America that at times it is hard to tell exactly where particular traditions originated. Rice, for example, was consumed in Spain, Western Africa, and Asia before 1492. Moreover, foods such as corn, potatoes, and tomatoes spread so widely during the early modern era that many people do not realize they were domesticated in what is now Latin America.

Encounters

Despite this long history of cultural blending, many of the Latino foods that Anglo Americans first encountered in the 19th century were of relatively recent origin. A late-18th century economic boom transformed subsistence societies of the Spanish Caribbean and northern New Spain into thriving commercial centers. The beneficiaries of this wealth began to consume more luxury foods, while the working classes struggled to maintain a nutritious diet even as they lost their land to export crops. Oblivious to historical change, 19th century Anglos applied their attitudes of manifest destiny to foods as well as people, and looked down on these cuisines as relics of the past, created by "savage" Aztecs, Caribs, and Africans. This racist attitude colored early cross-cultural interactions and long impeded Latinos from achieving full citizenship.

Late colonial prosperity allowed settlers on the northern borderlands to replace the sturdy, indigenous staple maize with European wheat, although they prepared it in the hybrid form of flour tortillas. Beleaguered by arid climate and Indian raids, rural Hispanic families generally sold their wheat to urban markets and fed themselves corn, either as tortillas or as pozole. When the Spanish Crown finally made peace with the Apaches and Comanches in the 1780s, however, settlers quickly expanded their irrigated fields, producing a surplus they could consume at home. The origins of wheat flour tortillas are unknown. Oral tradition in the borderlands often attributes them to Jewish settlers, who supposedly ate them during Passover, but such flatbreads were common throughout the Mediterranean. Wheat tortillas may also have been invented independently by Indian women who adapted familiar techniques to a novel grain. Regardless of their origins, these tortillas allowed rural folk to raise their status by eating Hispanic wheat, even if they could not afford the ovens and fuel for baking bread. Enormous, thin tortillas became a particular marker of the regional cooking of Arizona.[4]

A similar economic boom likewise stimulated a Hispanic culinary renaissance in Spain's Caribbean colonies, although not everyone shared in the windfall. The local sugar industry began to revive when the British occupied Havana in 1762, importing slaves and technology. The spread of abolition, beginning with the Haitian slave revolt of 1791, reduced competition for Spanish sugar. Coffee also became a significant export crop in the 19th century, particularly in the highlands of Puerto Rico. As historian Cruz Miguel Ortiz Cuadra has observed, the growth of Antillean plantations displaced local rice cultivation along with a range of indigenous root crops. Wealthy planters and merchants used the profits from sugar and coffee to import rice and other prestigious foods such as wine, olive oil, capers, and salt cod, which they prepared using Spanish recipes such as the soupy Valencian rice dishes, which became known in Puerto Rico as asopao de pollo (rice with chicken). Slaves and poor farmers ate more imported rice as well, although the machine-milled grain was less nutritious than the varieties they had formerly milled by hand. Unable to afford the meats and condiments of the rich, they fell back on the relatively monotonous although basically sound combination of rice and beans, the moros y cristianos of Cuba or red beans called habichuelas in Puerto Rico.[5]Whether on the borderlands or in the Caribbean, the localization of European foods gave residents new opportunities to demonstrate their ties with Hispanic civilization.

These connections remained strong even after the U.S. annexed the northern half of Mexico in 1848. Although Mexican residents of the San Francisco bay area were soon overrun by '49ers, more isolated settlements in southern California, south Texas, New Mexico, and Arizona preserved their cultural autonomy. Anglo newcomers to these areas often married into elite families, thereby acquiring a taste for Mexican food. Cookbooks also helped to preserve cultural ties, and over time they became treasured family heirlooms. Encarnación Pinedo published El cocinero español (The Spanish Cook, 1898), perhaps the first Latino cookbook, as a tribute to California-Mexican cookery. A manuscript volume by Refugio de Amador, preserved in the Rio Grande Historical Collections at New Mexico State University, contains recipes for torta de cielo (heavenly cake), turrón de Oaxaca (nougat), and jamoncillos de almendra (fudge squares).[6]

Latino culinary traditions also took root in port cities along the Atlantic seaboard and the Gulf of Mexico. Antillean communities were founded by merchants in commercial hubs such as New York City and New Orleans, as well as by the children of wealthy planters who studied in American schools. By the 1850s, they were joined by working-class Cubans and Puerto Ricans employed in garment and cigar factories of New York City and Ybor City, near Tampa, Florida. Bodegas (grocery stores) and restaurants catered to the immigrants' desire for familiar foods.

Many early Latino restaurants tried to attract a crossover clientele, but Anglos often refused to equate Spanish or Mexican cuisine with fine dining. With the completion of the Southern Pacific Railroad in the late 1870s, Mexican entrepreneurs in San Antonio, Texas, and Los Angeles, California, appealed to the growing tourist trade by opening elegant restaurants with names such as El Cinco de Mayo (The Fifth of May) and El Globo Potosino (The Balloon), located in San Luis Potosí, a famously rich mining town. These establishments offered Hispanic and Mexican favorites such as albóndigas (meatballs) and mole de guajolote (turkey in chile sauce), along with French and American dishes. Within a few years, however, most had disappeared from city directories, to be replaced by restaurants with French names.[7]

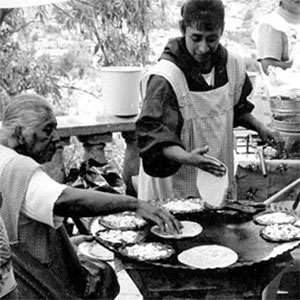

When Mexican food became the subject of culinary tourism, Anglos sought out exotic street food, not elegant restaurants. Many working-class Mexicans supplemented their household incomes by selling food during civic and religious festivals, and the growth of tourism made their occasional stands into a nightly pageant in streets and plazas. Vendors in San Antonio were gendered female in the popular imagination, as "Chili Queens," while in Los Angeles they were more often associated with masculine tamale pushcarts, although men and women of diverse ethnic groups sold chili and tamales in both cities. Stereotypes of Mexican food as painfully hot and potentially contaminating were conflated with the supposed sexual dangers of the "Chili Queens." Anglo journalists meanwhile accused tamale vendors of criminality and labor activism. Although a popular tourist attraction, vendors were constantly harassed by police and urban reformers, who sought to restrict them to segregated locations such as San Antonio's Milam Plaza.[8]

By the end of the 19th century, Latino foods had become firmly established in the national consciousness with an image of "safe danger." They represented an exotic experience for tourists to test their manhood by flirting with "Spanish" women and risking the strong flavors of chile peppers, garlic, and oil. Yet the food appealed not just to Bohemian slumming but also to working-class ethnics, who learned that they could find a tasty and inexpensive meal in Latino restaurants. Thus, Latino foods soon spread beyond their ethnic and geographical origins; for example, black vendors carried tamales from San Antonio all the way to the Mississippi delta. Cross-cultural exchanges, often based on unequal power relations, continued with the growth of the food processing industry.

Industrialization

Food processing was one of the largest industries in the U.S. during the Gilded Age, as it remains today, and then as now, migrant workers performed the difficult and poorly paid labor in fields and factories that made these businesses profitable. Yet Latino contributions to industrial food have scarcely been limited to manual labor. Historian Donna Gabaccia has noted the paradox that although immigrant entrepreneurs developed culinary icons ranging from hamburgers and hotdogs to Fritos and tacos, national markets for these products generally have gone to corporations with little connection to the communities of origin.[9]Because corporate advertising has had such a prominent role in the mainstream marketing "if not in the technological innovation" of Latino and other ethnic foods, exotic and often disdainful stereotypes from the 19th century have persisted.

The history of chili con carne illustrates the industrial appropriation and distancing of foods from their Latino origins. Businessmen such as Willam Gebhardt capitalized on the popularity of Mexican vendors by marketing chili powder made from imported peppers mixed with spices. Chicago meatpackers added chili con carne to their line of canned products in order to disguise inferior cuts of meat. Chili con carne acquired new forms and flavors as it spread across the country. African American cooks in Memphis put it on spaghetti as "chili mac," while in Ohio and Michigan hot dogs with chili became known as "coneys." In the 1920s, Macedonian immigrant Tom Kiradjieff added cinnamon and other spices to his recipe for "Cincinnati chili," which he served on spaghetti with optional cheese, onion, and beans. Chili with beans became a national staple during the hard times of the Great Depression. Some Anglo Texans eventually denied the Mexican origins of chili con carne, although the cowboy cooks credited with the recipe also learned their ranching skills from Mexican vaqueros.

The well-known story of chili has tended to obscure a parallel history of food processing innovation and entrepreneurship within Latino communities. Labor migrants traveling out of the Southwest to work in Midwestern railroads, factories, and agriculture skillfully improvised familiar foods in makeshift kitchens. By the 1920s, Mexican merchants in cities such as Chicago and St. Louis offered a range of fresh and dried ingredients, kitchen utensils, and prepared foods. Some of these items were imports from Mexico, including the Clemente Jacques line of canned chiles and sauces. Others were manufactured in the U.S. by companies such as the Los Angeles-based La Victoria Packing Company. Fabian García, a Mexican-born graduate of the New Mexico College of Agriculture and Mechanic Arts, established the first scientific breeding program devoted to chiles, providing the basis for the commercial agriculture in the state. Mexican merchants in San Antonio, who congregated along Produce Row, organized the shipping of tropical fruits and vegetables to the U.S.[10]

Mexicans and Mexican Americans also pioneered the mechanization of tortilla making, although it remained a cottage industry for decades due to the cultural insistence on freshness. By the turn of the century, steel mills had replaced the burdensome daily labor of grinding corn dough, at least in urban areas of Mexico and the Southwest. In 1909, San Antonio corn miller José Bartolomé Martínez patented a formula for dehydratednixtamal flour called Tamalina. Although the local market was not yet ready for a dried product, Martínez's Aztec Mills did a brisk business in daily deliveries of fresh tortillas. Martínez also transformed the leftover masa de maíz (corn dough) into the first commercial corn chips, called tostadas, which he sold in eight-ounce wax bags beginning around 1912. Some scholars have claimed that Elmer Doolin used his recipe as the basis for Fritos brand corn chips. Although Martínez's legacy was usurped by others, Latino food businesses continue to prosper throughout the Southwest. The Sanitary Tortilla Company, for example, remains to this day a San Antonio institution with legions of customers still loyal to cantankerous 1920s machines.[11]

The growing influence of Puerto Ricans also stimulated food commerce and industry in New York City. Along with Cuba and the Philippines, the island had become an American colony following the Spanish-American War in 1898. With the Jones Act of 1917, Puerto Ricans gained U.S. citizenship and also became liable for military service, both of which spurred migration. Historian Virginia Sánchez Korrol has observed that restaurants with names like El Paraiso (Paradise) became important community centers in Spanish Harlem, comforting newcomers with familiar favorites including arroz con gandules verdes (rice with green pigeon peas), codfish fritters, and the plantain dishes known as mofongo and tostones. La Marqueta, an open-air market in the neighborhood, supplied shoppers with Antillean fruits and vegetables.[12] Historian Frederick Douglass Opie has argued, moreover, that Latino migrants from the Caribbean also had a significant influence on the development of African American foods as early as the Harlem Renaissance.[13]

The most prominent Latino merchant, Prudencio Unanue, migrated as a young man from his Basque homeland to Puerto Rico and ultimately built a Caribbean food empire called Goya. By the late 1920s he was importing foods for the Spanish colony in the Chelsea neighborhood of New York City, but the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939) disrupted his source of supply, forcing him to diversify. His decision to market Caribbean food instead proved a profitable one in the postwar era with the tremendous growth of migration from Puerto Rico and then neighboring islands. Goya soon began opening packinghouses and supplying local markets in the Caribbean as well.[14]

Fast food restaurants emerged as another important segment of the Latino food market in the postwar period. Taco Bell has become so dominant in this field that even many Latinos may believe the company website, which claims that the taco shell, a tortilla pre-fried in a U-shape, was invented in the early 1950s by a San Bernardino, California hotdog vendor named Glen Bell. This account of the origins of the fast food taco also fits with critics of "McDonaldization," who argue that modern technology and corporate standardization by outsiders has destroyed the authentic flavor of peasant cuisines. Nevertheless, a search of U.S. Patent Office records reveals that the original taco shell patent was filed in the 1940s by Juvencio Maldonado, a Mexican migrant who operated a successful New York City restaurant called Xochitl from the 1930s to the 1960s. Bell built his fortune not by employing modern technology but rather by franchising ethnic exoticism and allowing Anglo consumers to sample Mexican food without crossing informal lines of segregation in the postwar era.[15]

Despite the availability of Latino brands such as Goya, for decades most American consumers seemed to prefer Taco Bell, Frito-Lay, and Old El Paso. These companies not only transformed the flavors of Latino foods "Glen Bell based his salsa on chili dog sauce "but also used racially charged advertisements such as the Frito Bandito of the 1960s or the Taco Bell dog of the 1990s, which compared Latinos to criminals and animals. Yet consumers have become increasingly knowledgeable about and favorable toward foods that are actually made by Latinos, largely because of the recent spread of migrant restaurants and bodegas across the country.

By the late 20th century, Latino foods were achieving unprecedented diversity in the U.S. Before that time, Latinos were primarily migrants from northern and central Mexico, if their families had not already lived in Florida, the Southwest, or Puerto Rico before those territories were acquired by the U.S. The arrival of people from throughout Latin America came not from the Immigration Reform Act of 1965, which actually imposed restrictive quotas for the first time on people born in the Americas, but rather from Cold War involvement in the region. Each new conflict brought displaced populations to the U.S., from the Cuban Revolution of 1959 to the South American military dictatorships of the 1970s and the Central American civil wars of the 1980s. Political exiles and economic migrants introduced new restaurant cuisines at the same time that Latin American food processing firms began making inroads into domestic markets, including basic staples (Maseca tortillas, Bimbo bread), fast food (Pollo Campero), and alcoholic beverages (Chilean wines, Corona beer). Thus, the growing demographic importance and rising professional status of Latinos has contributed to a mainstream recognition of and desire for Latino foods.

Newly arrived migrants wasted little time in recreating their national cuisines. In the 1960s, Cuban exiles transformed Miami into Little Havana, centered on the nostalgia-filled restaurants, cafes, and street vendors of Calle Ocho (Eighth Street). Middle-class housewives meanwhile consulted treasured copies of Cocina al minuto (Cooking to the Minute, 1956), even though the author, Nitza Villapol, was widely considered to be a traitor for having remained behind in Cuba after the end of the Cuban Revolution. A decade later, Dominicans established a presence in the Washington Heights area of New York City, and bodegas were soon filled with dried shrimp and live chickens to satisfy Dominican tastes. When the Adams Morgan neighborhood of Washington, DC, became home to Central American migrants in the 1980s, restaurants began selling pupusas and gallo pinto ("spotted rooster," a Nicaraguan and Costa Rican version of rice and beans). Mexican regional cuisines have also became more diverse, with Zapotec and Mixtec mole sauces available in Oaxacan restaurants in Los Angeles, while chain migrations have brought Mayan salbutes (tostadas) from the Yucatán to San Francisco.

One promising change in recent times has been a growing acceptance of Latino foods as fine dining. The 1960s counterculture prompted a skeptical attitude toward industrial processed foods and new interest in the peasant cuisines of the Global South, including Latin America. Although the desire for more authentic foods has at times exoticized Latinos, sophisticated diners have flocked to upscale restaurants serving Peruvian, Caribbean, Brazilian, Mexican, and other Latin American cuisines. Diverse national favorites have also come together in "Nuevo Latino" restaurants, which feature eclectic combinations of such foods as ceviche (marinated fish), plantains, grilled meats, and salsas.

Despite these gains, working-class Latinos still suffer pervasive discrimination. Many taco truck owners confront the same forms of harassment suffered a century earlier by the "Chili Queens," even when these vendors are U.S. citizens.[16]Health officials meanwhile target Latino foods as contributing to a supposed epidemic of obesity and diabetes. While it is true that poor Latinos suffer disproportionately from these conditions, as do the working classes more generally, stigmatizing "unhealthy behaviors" has been a longstanding theme of middle-class reform efforts toward the poor and foreigners. A century ago, migrant diets were criticized for excessive whole grains like maize and not enough fat and protein, exactly the opposite of advice given today. Sociologist Airín Martínez has found that migrant Latino mothers have basically sound ideas about comiendo bien (eating well) and that they often go to great lengths to provide healthy food for their families. But like 19th century migrants, their efforts are undermined by the structural constraints of poverty and limited access to fresh foods.[17]

Latino cooks have clearly made significant contributions to the potluck that constitutes the national cuisine. Latin America's mestizo cuisines offer unique combinations of foods from around the world. They feature not the costly ingredients and elaborate techniques of French haute cuisine but rather hearty dishes with vibrant flavors. First shunned by Victorian diners and later imitated by the food processing industry, Latino foods have recently gained acceptance at the center of the table. If we are what we eat, then the U.S. is becoming an increasingly Latino nation.

Jeffrey Pilcher, Ph.D., is a Professor of History at the University of Minnesota. He specializes in the history and culture of Mexico, Latin America, and the Caribbean, and the history and culture of food. His major works include Planet Taco: A Global History of Mexican Food; Food in World History; The Sausage Rebellion: Public Health, Private Enterprise, and Meat in Mexico City; and ¡Que vivan los tamales! Food and the Making of Mexican Identity. He received his Ph.D. in History from Texas Christian University.

Endnotes

[1] Sophie D. Coe, America's First Cuisines (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1994), chapters 2-3.

[2] Jeffrey M. Pilcher, ¡Que vivan los tamales! Food and the Making of Mexican Identity (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1998), chapter 2.

[3] Elinor G. K. Melville, A Plague of Sheep: Environmental Consequences of the Conquest of Mexico (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997).

[4] Jeffrey M. Pilcher, Planet Taco: A Global History of Mexican Food (New York: Oxford University Press, 2012), chapter 2.

[5] Cruz Miguel Ortiz Cuadra, Puerto Rico en la olla, ¿Somos aún lo que comimos? (Aranjuez, Spain: Ediciones Doce Calles, 2006), 58-64.

[6] Rio Grande Historical Collections, New Mexico State University Library, Las Cruces, Amador Family Papers, MS 4, box 7, folder 1, Refugio Ruiz de Amador manuscript cookbook.

[7] Victor M. Valle and Mary Lau Valle, Recipe of Memory: Five Generations of Mexican Cuisine (New York: The New Press, 1995), 131; Pilcher, Planet Taco, chapter 4.

[8] Jeffrey M. Pilcher, "Who Chased Out the 'Chili Queens'? Gender, Race, and Urban Reform in San Antonio, Texas, 1880-1943," Food and Foodways 16, no. 3 (July 2008): 173-200.

[9] Donna R. Gabaccia, We Are What We Eat: Ethnic Food and the Making of Americans (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1998).

[10] Margarita Calleja Pinedo, "Los empresarios en el comercio de frutas y hortalizas frescas de México a Estados Unidos," in Empresarios migrantes mexicanos en Estados Unidos, ed. M. Basilia Valenzuela and Margarita Calleja Pinedo (Guadalajara: Universidad de Guadalajara, 2009), 307-43.

[11] Vanessa Fonseca, "Fractal Capitalism and the Latinization of the U.S. Market" (Ph.D. dissertation, University of Texas, Austin, 2003), 28-43.

[12] Virginia E. Sánchez Korrol, From Colonia to Community: The History of Puerto Ricans in New York City, rev. ed. (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1994), 55-56, 63-65.

[13] Fredrick Douglass Opie, Hogs and Hominy: Soul Food from Africa to America (New York: Columbia University Press, 2008), 139-53.

[14] Joel Denker, The World on a Plate: A Tour through the History of America's Ethnic Cuisine (Boulder, CO: Westview, 2003), 147-62.

[15] Pilcher, Planet Taco, chapter 5.

[16] Vicki Ruiz, Citizen Restaurant: American Imaginaries, American Communities," American Quarterly 60, no. 1 (March 2008): 1-21.

[17] Airín Martínez, Comiendo Bien: A Situational Analysis of the Transnational Processes Sustaining and Transforming Healthy Eating among Latino Immigrant Families in San Francisco" (Ph.D. dissertation, University of California, San Francisco, 2010).

The views and conclusions contained in this document are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as representing the opinions or policies of the U.S. Government. Mention of trade names or commercial products does not constitute their endorsement by the U.S. Government.

Part of a series of articles titled American Latino/a Heritage Theme Study.

Last updated: July 10, 2020